Here is a sobering fact: we live on an Island and the sea is rising.

The consensus among coastal scientists is that our children or grandchildren will see a sea level rise of about one metre in this century, an estimate that does not even take into account the rapid rate of melting glaciers. The New York Times reported last week that “the arctic ice cap melted this summer at a shocking pace, disappearing at a far higher rate than predicted even by the most pessimistic experts in global warming.”

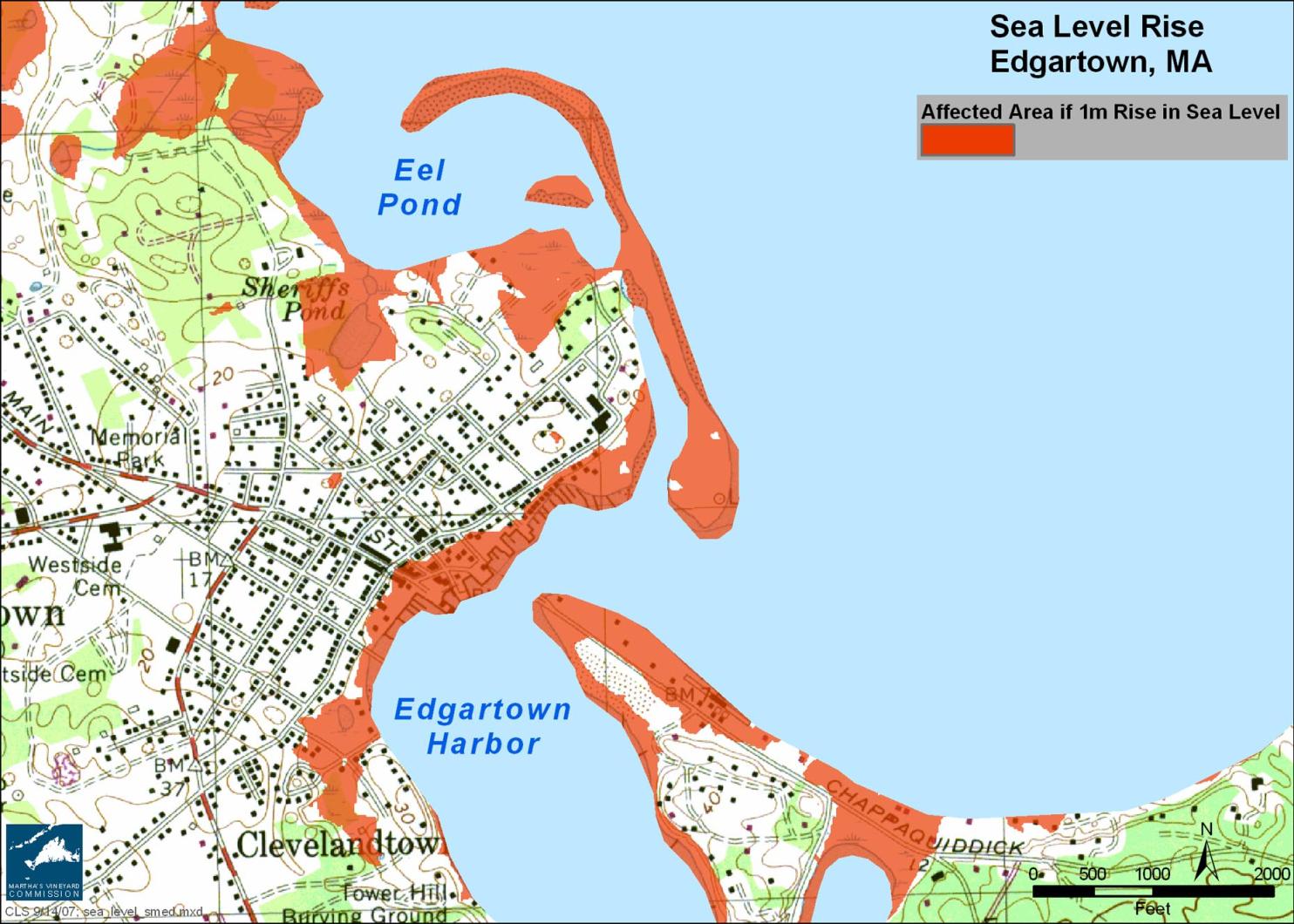

A one-metre sea level rise (one metre is a little over three feet) would inundate portions of the Felix Neck Wildlife Sanctuary and the inland shore of Sengekontacket Pond. State Beach would barely exist. Much of the land between Menemsha Pond and the Sound would be under water, as would a serious chunk of downtown Edgartown.

The sea is rising because glaciers and ice sheets are melting and warmer water is expanding. The Boston Globe recently reported that a one meter rise will happen “regardless of any future actions to curb greenhouse gasses.”

According to the U.S Geological Survey, most of Nantucket and parts of Cape Cod and the Vineyard are “areas of high sea-level rise vulnerability in the Northeast.” The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reports that “some of the most economically important vulnerable areas are recreational resorts on the coastal barriers of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts.”

Here we sit, out in the deep blue sea, a summer resort community with an economy directly linked to our vulnerable shoreline. The beaches and salt marshes are a buffer zone between land and sea. They act like shock absorbers, giving the stormy sea a safe place to crash before spilling landward. Without them coastal roads and buildings will be hit that much harder in a storm.

Sea level rise causes flooding of low-lying areas, loss of wetlands, erosion of beaches, saltwater contamination of drinking water, decreased longevity of low-lying roads, bridges and causeways and an increased vulnerability to coastal storms. Sea level rise is projected to permanently inundate low-lying coastal areas. A Northeast Climate Impacts Assessment (NCIA) published by the Union of Concerned Scientists adds that, “because of the erosive impact of waves, especially storm waves, the extent of shoreline and wetland loss is projected to be many times greater than the loss of land caused by the rise in sea level itself.”

You may hear people tossing around the term 100-year storm. Major coastal flooding events are called 100-year storms, meaning there is a one per cent chance of such a storm happening in any given year. According to the NCIA report, today’s 100-year coastal floods are projected to occur much more often. For example, “the 100-year storm frequency for Woods Hole is projected to recur every nine to 21 years.”

The Island’s coastal planners and managers need to address sea level rise. It is unavoidable. It will intensify threats to life and property from both hurricanes and northeasters. It will raise havoc with an Island economy based on seashore recreation.

Some general recommendations for adapting to the rise include stricter building codes, building setbacks in coastal areas, investments in infrastructure, ongoing beach renourishment and elevating shoreline homes. The state of Maine has already issued a report titled Anticipatory Planning for Sea-Level Rise along the Coast of Maine. The key premises underlying its many recommendations are:

• The state should protect and strengthen the ability of natural systems to adjust to changes in shoreline position.

• The state should prevent new development which is likely to interfere with the ability of natural systems to adjust to changes in shoreline position.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report states flatly that public institutions are responsible for adapting their own plans to appropriately anticipate climate change. And the NCIA report cites a daunting complication: “Coastal managers are faced with the difficult challenge of adapting regulations to protect against increasing risks rather than historic risks.”

Poor Chicken Little; the sky wasn’t falling after all. But there is no doubt that the water surrounding the Vineyard is rising and its impacts cannot in good conscience be ignored.

Liz Durkee is the Oak Bluffs conservation agent and a frequent contributor to the Gazette.

Comments

Comment policy »