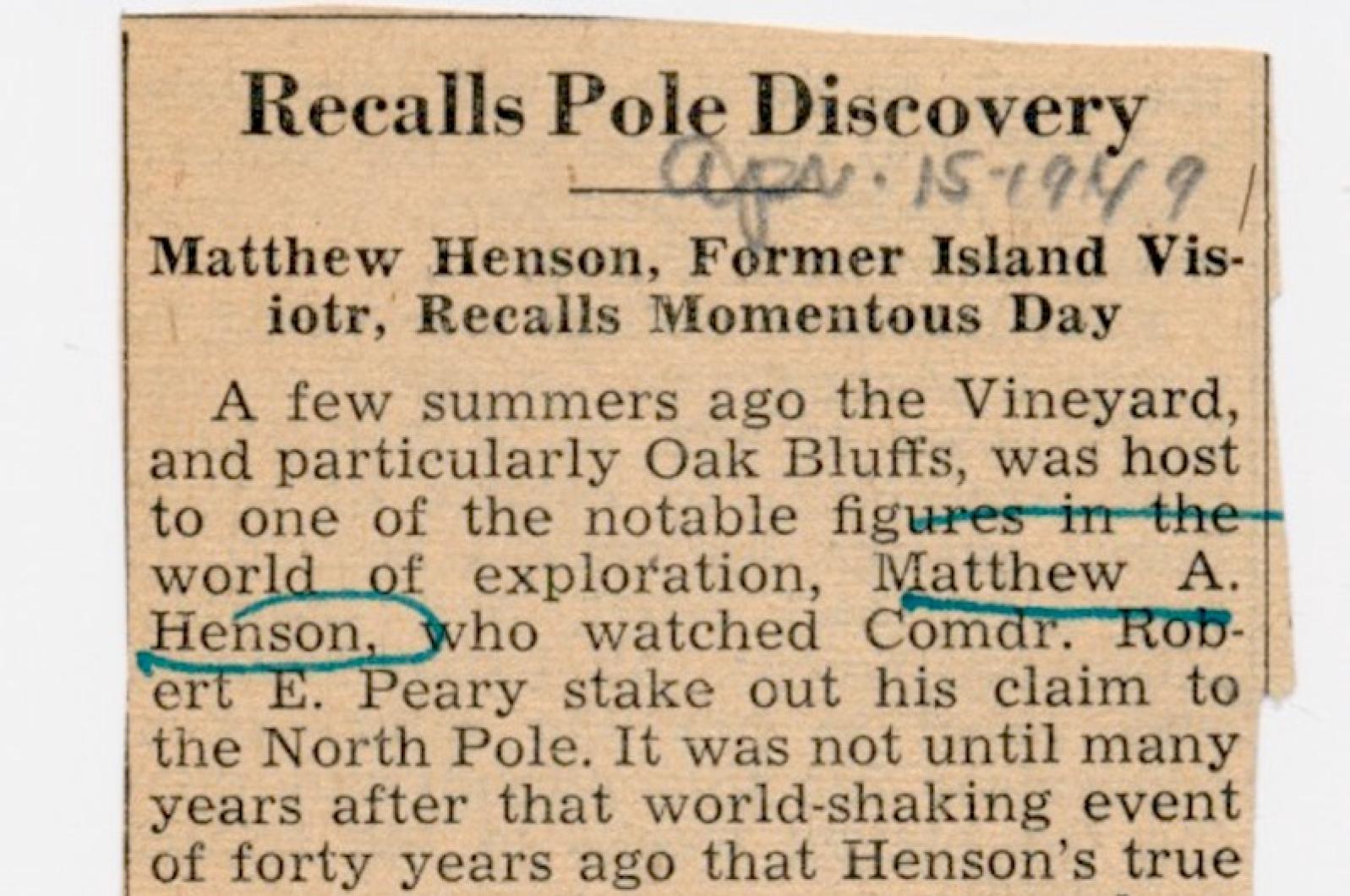

A few summers ago the Vineyard, and particularly Oak Bluffs, was host to one of the most notable figures in the world of exploration, Matthew A. Henson, who watched Comdr. Robert E. Peary stake out his claim to the North Pole. It was not until many years after that world-shaking event of forty years ago that Henson’s true place in the picture won general acceptance and his heroism on the icy journey became widely known.

Four decades after the discovery of the North Pole, April 6, 1902, Mr. Henson, now 83, rated interviews by the New York papers. The following paragraphs are from William M. Farrell’s article in the New York Times.

On a bench in Pennsylvania Station, Mr. Henson amiably retold some of his stories. This, he said, was the extent of his observance of the anniversary of the day on which he and Commander Peary, who was made a rear admiral in 1911, marked the success of fifteen years together striving toward the North Pole. Having retired in 1936 on a pension from the Customs Service, Mr. Henson chooses his daily activities freely, and yesterday he was making visits.

The stop in mid-Manhattan reminded the veteran Arctic explorer of how he had traveled about the country for a year, after his return from the final Peary expedition. That trip, under the management of the late William A. Brady, was the only time he made anything like big money, but it nearly killed him, he said.

The lecture trip was at least profitable, but the Arctic explorations were their own reward. “I never got a dime out of them, until the last one I was paid $25 a month,” Mr. Henson said. “And that was just because I’d just got married.”

A Chance Meeting

He had been working in the fur department of a Washington haberdashery when Peary came in to buy a fur cap. What he wanted with it at the moment is not clear, for he was about to start on a trip to balmy Nicaragua. He mentioned this to a clerk, who introduced Mr. Henson to him, with the result that Mr. Henson became the Navy officer’s “valet”.

But Mr. Henson quickly convinced his employer that he would be more useful “in the field” than as a valet, and from then on the two men worked together at many different and unusual tasks. Commander Peary finished his assignment in Nicaragua and turned his attention to Polar exploration.

Mr. Henson went along with that idea to the extent that he became a sledge builder, hunter, carpenter, igloo maker and one of the best dog sled drivers in the North. Peary, he said, never became proficient as a driver because he didn’t learn to use a whip properly. After his toes were frozen off, on one expedition, he rode a good deal on his sled.

But Mr. Henson’s feet never were frozen, and though occasionally he would see his fingers turning ominously white, he always managed to warm them against his body before the frost-bite spread.

Mr. Henson keeps in occasional touch with others who were on all but the climactic last drive of Peary’s final expedition, and once in a while he himself is honored for his own part in it. He has been on radio programs from time to time, and on last Tuesday night he made his first appearance on television. But he is too nervous to do much of this, he said calmly.

Mr. Henson said he had heard as recently as a year ago that at least one of the four Eskimos who made the final march with Peary still lived. But he didn’t suppose there would be any observances of the anniversary, so far as the Eskimos were concerned.

“They took it just for granted that we were crazy, looking for the North Pole,” he said. “They asked us: ‘You didn’t get anything, did you?’ But we did.”

Comments