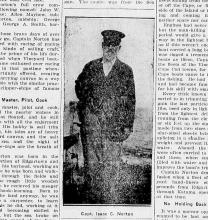

At various times in recent years the name of Captain Isaac C. Norton has figured in print. The captain is one of those remarkable characters who seldom do anything that is not worthy of passing mention.

Having arrived at the age of eighty-two-years, of which thirty or more are never guessed at, his trim six-foot figure with military shoulders and snow-white vandyke beard is a familiar sight in Vineyard Haven and causes no little comment whenever he is seen, even by those who have known him for a lifetime.

This is mainly because of his physical condition. His stride is free and springy, and is capable of distancing men young enough to be his grandsons. His grip is like iron, and his hearing as keen as a cat’s. From his deeply- tanned face his sea-blue eyes shine with the sparkle of youth unassisted by glasses and missing nothing.

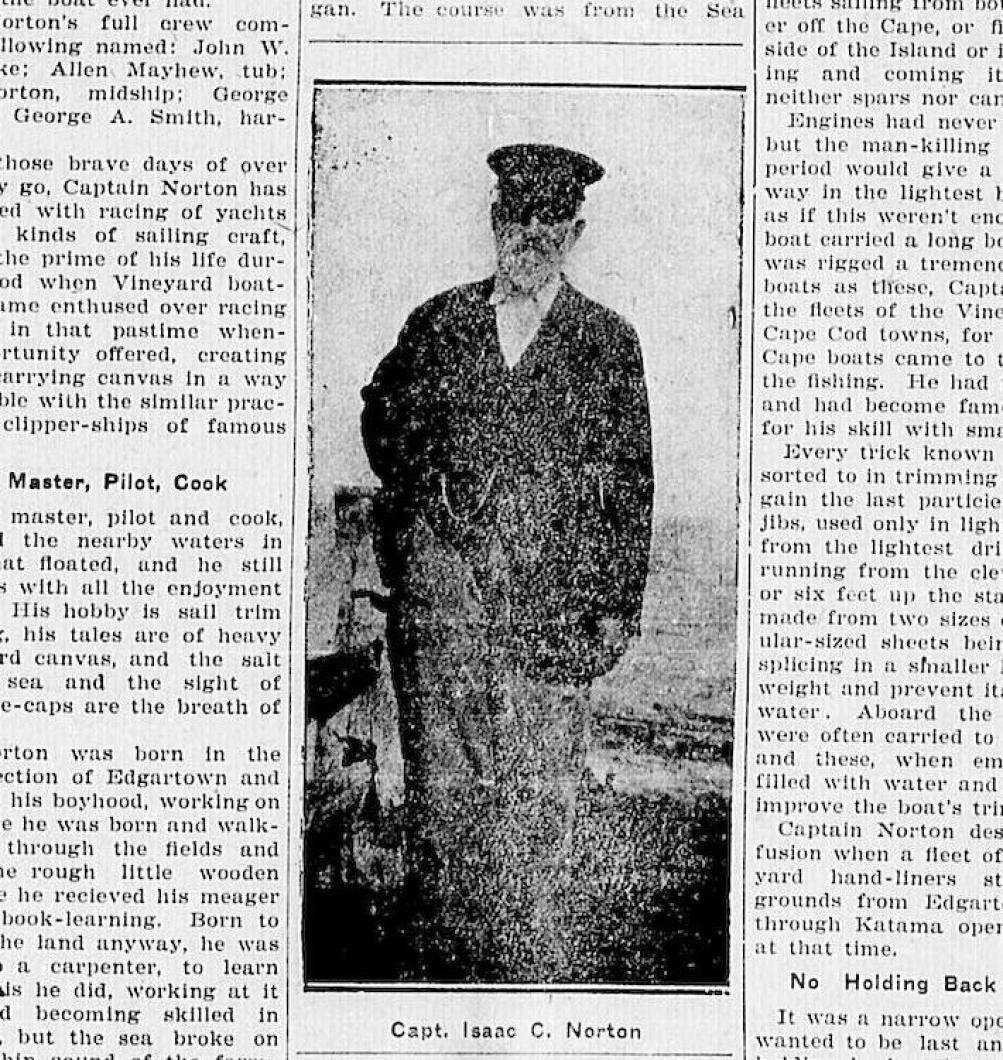

In Connection with boat-racing in all its branches, the captain’s career is prominent in Vineyard history. He is one of the two survivors of the undefeated whale-boat crew of the Vineyard, its captain, in fact and the only captain that the boat ever had.

Captain Norton’s full crew comprised the following named: John W. Gordon, stroke; Allen Mayhew, tub; Cyrus B. Norton, midship; George Fisher, bow; George A Smith, harpooner.

And since those brave days of over a half-century ago, Captain Norton has been associated with racing of yachts and all other kinds of sailing craft, having lived the prime of his life during that period when Vineyard boatmen first became enthused over racing and indulged in that pastime whenever an opportunity offered, creating records and carrying canvas in a way only comparable with the similar practices in the clipper-ships of famous memory.

Seaman, Master, Pilot, Cook

As seaman, master, pilot and cook, he has sailed the nearby waters in everything that floated, and he still sails and rows with all the enjoyment of his youth. His hobby is sail trim and ballasting, his tales are of heavy winds and hard canvas, and the salt scent of the sea and the sight of tumbling white-caps are the breath of life to him.

Captain Norton was born in the Farm Neck section of Edgartown and there he spent his boyhood, working on the farm where he was born and walking to school through the fields and pastures to the rough little wooden building where he received his meager allowance of book-learning. Born to the farm, to the land anyway, he was apprenticed to a carpenter, to learn the trade. This he did, working at it diligently, and becoming skilled in wood-working, but the sea broke on the beach within sound of the farmhouse, the smell of salt and sea-weed was borne inshore on the wings of every easterly wind and the gulls swept across the planted fields, calling, calling always to him.

And so, as a boy and man, he went to the sea. First in small row-boats in which he paddled about, later in small fishing craft, and finally, in the Revenue Cutter service, where he spent several years.

Actually, it might be said that the captain’s first training in racing boats and vessels began in this service. Revenue cutters of his day were schooners, and top-sail schooners at that, crossing top-sail yards on fore and mainmasts, and even royal-yards above them in certain cases. A seaman on a revenue cutter had to be a fore-and-aft and a square-rigged man all at once.

There was work for these swift cutters too. In these days there is much talk of smuggling, but sixty-odd years ago the government vessels regarded every craft with suspicion. The sea was filled with ships and brigs bound from the West Indies and South American ports and no man could tell how much contraband might be stowed in the hold of any of them.

Seven Years on Revenue Cutter

By day and night, in weather of every variety, and in summer and winter, the revenue cutter sailed on its patrol, chasing vessels, overhauling and searching them, often discovering smuggled goods concealed somewhere aboard. And there was other work, of looking for disabled craft, taking shipwrecked men from foundering hulks or bearing home the pitiful remains of such victims. All this had a strong bearing on the future career of Captain Norton as will be shown, and for seven years he remained in the cutter service, serving in every berth from mess-cook to carpenter, as he says.

During those years he sailed on such famous old crafts as the J. C. Dobbin, J. S. Black, Active, Rescue and the steam cuter Gallatin.

He was, to use his own words “heading toward thirty” when he returned to the Vineyard and took up carpentering again for a time, and it was at just about this period in his career that the whale-boat racing began.

It started first when a boat and crew of New Bedford whalers came to the Vineyard with a view to challenging a crew from Edgartown. The Edgartown boys were not slow to accept the challenge, but they were not able to muster a full crew of bona fide whalemen although they did have a captain who had had such whaling experience. But their boat was a poor one and half filled with water before the race was completed and Edgartown lost the race.

This was not to be endured. To begin with, boat racing had never been indulged in before, so far as Captain Norton knows, and the thrill of this first race was something that had never before been experienced. The Vineyard crew were confident that they could do better, much better, and they resolved that they would demonstrate to the world that they could.

The first step was to obtain a good boat, and they ordered one built. This craft was constructed by Uriah Morse of Edgartown, and built according to the standard measurements of the regulation whaleboat. But Morse had ideas of his own about models, and he put fullness in place where whaleboats had never before shown it, and likewise cut away in unexpected places. The result was a boat that was built for high speed under oars, which was exactly what was required.

Whaleboat Still Survives

It might be mentions, incidentally, that the boat, still sound and solid, is hanging in the barn of the late Cyrus Norton, brother of Captain Isaac and mid-ship oarsman of the famous crew. She was never used after the racing came to an end.

When all was ready, the racing began. The course was from the Sea View pier at Oak Bluffs, around East Chop Buoy and back, three miles, as it was calculated. The Vineyard boat was given a coat of black lead on her bottom before each race and was never allowed to touch ground. Men picked her up and carried her to the water, wading in until there was sufficient depth to float her.

A whaleboat carries five oarsmen, two oars stroking on one side and three on the other. These oars were of different lengths to balance the pull, and the long mid-ship oar of Cyrus Norton was eighteen feet long, the shortest, fourteen.

No one ever timed this boat when she was under way, but Captain Isaac, who was given command as soon as she was launched, states that her stern settled until her ribands were flush with the water. The crew were accustomed to removing coats and shirts as soon as they were warmed up, and tossing them into the bow. “Three strokes of the oars and those clothes would be in the stern-sheets!” chuckles Captain Norton, showing that the oarsmen lifted the boat with every stroke.

The boat was never defeated. Again and again the whalemen of New Bedford met and raced the Vineyard crew. “A crew of farmers” as Captain Norton calls them, but always the farmers won and always it was Capt’n Ike who held the steering oar.

The last race that was scheduled, was planned after about six years of the sport, and was to be in the Acushnet River. The Vineyard crew took their boat to New Bedford, and got her ready for the race. The New Bedford men were also ready and in their boat, but they refused to race. Apparently they could not stand the disgrace of being beaten on their home ground, or water. This was the end of whale boat racing as far as the Vineyard was concerned, but the Vineyarders pulled over the course in sight of the assembled spectators, and as they shot across the finish line, Cyrus Norton, at the command of his captain, snapped the big mid-ship oar into three pieces, just to demonstrate the amount of power there was behind his stroke.

Raced to Fishing Grounds

Sailing races had begun, in yachts and in fishing-boats and the Vineyarders were keen enthusiasts in this sport. Edgartown and Vineyard Haven already possessed a few sloops that were regards as “smart” and the cat-boat was coming into its own. Hand-line fishing was followed extensively, fleets sailing from both towns, to gather off the cape, or fish off the south side of the Island or in the sound. Going and coming it was race and neither spars nor canvas were spared.

Engines had never been dreamed of, but the man-killing main-sails of the period would give a cat-boat steerage way in the lightest breath of air, and as if this weren’t enough, nearly every boat carried a long bow-sprit on which was rigged a tremendous jib. In such boats as these, Captain Norton raced the fleets of the Vineyard and of the Cape Cod towns, for large numbers of Cape boats came to the Vineyard for the fishing. He had turned fisherman, and had become famous far and near for his skill with small craft.

Every trick known to man was resorted to in trimming hulls and sails to gain the last particle of speed. The jibs, used only in light airs, were made from the lightest drill, with a boom running from the clew to a point five or six feet up the stay. Sheets were made from two sizes of line, the regular-sized sheets being lengthened by splicing in a smaller line to lessen the weight and prevent its dragging in the water. Aboard the fishermen, tubs were often carried to wash the fish in, and these, when empty, were often filled with water and shifted about to improve the boat’s trim.

Captain Norton describes the confusion when a fleet of Cape and Vineyard hand-liners started for the grounds from Edgartown, sailing out through Katama opening as they did at that time.

No Holding Back at Opening

It was a narrow opening, but no one wanted to be last and there was no holding back unless it was necessary to prevent going ashore. Crowding each other until they touched, the catboats stormed through the opening on the breast of the ebb tide that laid the water down as flat as a floor. But just through the opening, where the tide met the open ocean, there was always a sea heaving in, and the boats, traveling on a level surface, would meet this first sea and take it right aboard.

Once outside, the race was on until the grounds were reached. And once the fleet started for home, it began once more. “Never mind the mast, crack on and beat ‘em!” was the motto, and Captain Norton usually came in ahead of the rest. Knowledge of the tide helped him to a great extent at times, but he has always been recognized as a master in sail, and holds today a silver cup won in a regular catboat race.

Naturally enough, such skill became known, outside of the fishing fleet and yachtsmen began to bid for his services. Holding a pilot’s license, he could take the wheel of a yacht and steer her over any course along this section of coast. Numerous other Vineyard pilots did the same thing, and when several of them were racing each other, it added to the thrill. In this sort of racing the captain made quite as good a record for himself as in the catboats.

But he did not always race. Mention has been made of his pilot’s license. There was plenty of business for pilots at that time with vessels of all descriptions coming and going along the coast. By day and night, the pilots were on the alert for a chance to take one into port and they “had to do some brisk work” to get their vessels at times. Putting out in small round-bottomed boats that could easily be hoisted aboard the vessels, they usually rowed to meet them. Often Captain Norton was left West Chop at two o’clock in the morning and rowed to Sow and Pigs Lightship to meet a ship.

Received Congressional Medal

So through the years, the captain has continued to sail and row and race too, whenever he could. He has served as one of the crew of a wrecking lighter, where his skill was appreciated, and in 1898, when he was a youth of fifty, he steered a dory, pulled by Vineyard Haven men to the rescue of the crews of vessels ashore in the harbor. For this act he received the Congressional Medal, and the State Medal for saving life.

But his heart has always been with racing and he is interested in any development along that line. One of his pet theories is that the greatest speed is made with a sail that bags and he has no liking for the flat sail. The captain is looking forward to seeing the races for the Lipton Cup, and very probably would give any of the racing skippers some valuable pointers from his experiences gained in more than half a century of racing.

Comments