Fifty years ago this month, Hollywood production designer Joe Alves was searching for places to film a low-budget thriller called Jaws when he drove aboard a ferry in Woods Hole — headed for Nantucket.

“We didn’t have a location scout. It was just me, [because] it was going to be a cheap shark movie,” Mr. Alves recalled, speaking with the Gazette by phone from his Los Angeles home this week.

In search of the ideal setting for Amity Island, invented by Peter Benchley for his novel Jaws, Mr. Alves had already toured coastal Long Island before taking the author’s advice to try Nantucket, where the Benchleys summered for generations.

Had Mr. Alves made his scouting trip another day, it’s possible the entire history of Jaws — and the Vineyard — would have been different, with filming in Nantucket and Siasconset instead of Edgartown, Oak Bluffs and Menemsha.

But a winter storm was brewing offshore as he arrived in Woods Hole, at that time the Steamship Authority’s sole mainland port for departures to both Nantucket and the Vineyard.

“I got on the Nantucket boat but it was so rough, we got halfway and the captain said ‘We can’t make it all the way,’ so we turned around and came back,” Mr. Alves said.

“So I’m standing in Woods Hole, I can’t get to Nantucket, I see the ferry to Martha’s Vineyard and I said, ‘Okay, it’s only eight miles away,’ and I exchanged my ticket,” he said.

Mr. Alves spent that night at the Mansion House in Vineyard Haven, where he watched the Buffalo Bills beat the New York Jets as Bills running back O.J. Simpson surpassed 2,000 yards of rushing for the season.

Next morning — Dec. 17, 1973 — Mr. Alves got back in his car and started exploring, on the lookout for places to menace with the mechanical monster shark his production team was developing in California.

“I needed a bay to shoot the shark, [with] a nice sandy bottom,” he told the Gazette this week.

“We really wanted to shoot in the ocean, not in the back lot against a backdrop,” he said.

Mr. Alves soon found what he was looking for along State Beach in Oak Bluffs, where the wide waters of Nantucket Sound could accommodate his 25-foot creation.

“I thought, ‘We could shoot the water stuff here,’” he said.

Driving on to Edgartown, Mr. Alves was struck by its tidiness and coastal village scenery.

“Edgartown was perfect, with the picket fences and the wharf there . . . It’s such a beautiful little town,” he said.

In other words: Ripe for the chaos of a terrifying rampage by a killer sea beast that would transform it “from a happy place to a sad place,” Mr. Alves said.

In Menemsha, Mr. Alves found the film’s third iconic location: shark hunter Quint’s waterfront territory.

“I thought, ‘A big studio could have built this in a big empty lot,’” he said.

In fact, that could have happened with all of Jaws: executives at Universal Studios, which was bankrolling the film, weren’t inclined to splash out money on location shooting and viewed the mechanical shark with skepticism.

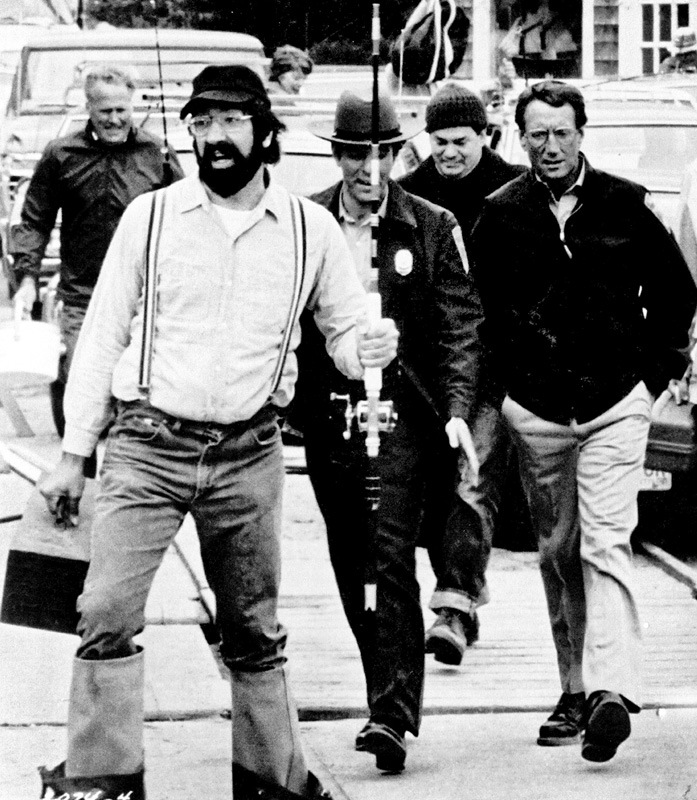

But Mr. Alves and director Steven Spielberg — still an up-and-coming filmmaker — had a heavyweight on their side: head of production Marshall Green, who had brought the Jaws novel to the studio at the suggestion of Cosmopolitan magazine editor Helen Gurley Brown.

“He was sort of excited about it, because he lived on a boat. Most people thought, ‘Who’s gonna make this dumb shark movie?’” Mr. Alves said.

Film producer Richard Zanuck was also on board with location shooting — but worried about doing it on the Vineyard, Mr. Alves said.

“Dick Zanuck was very concerned, because of the Kennedys and the Chappaquiddick thing [in 1969],” he said.

But after visiting the Island a second time with Mr. Spielberg — with whom he also scouted Marblehead — Mr. Alves had his Amity Island.

Now the Jaws team had to win over the real Islanders, beginning with town leaders.

“We had good vibes and we had some not-so-good vibes,” Mr. Alves recalled.

“The wealthy people of Martha’s Vineyard weren’t happy with a movie shooting there, [but] Steven wound up putting the selectmen in the movie and they got excited about that.”

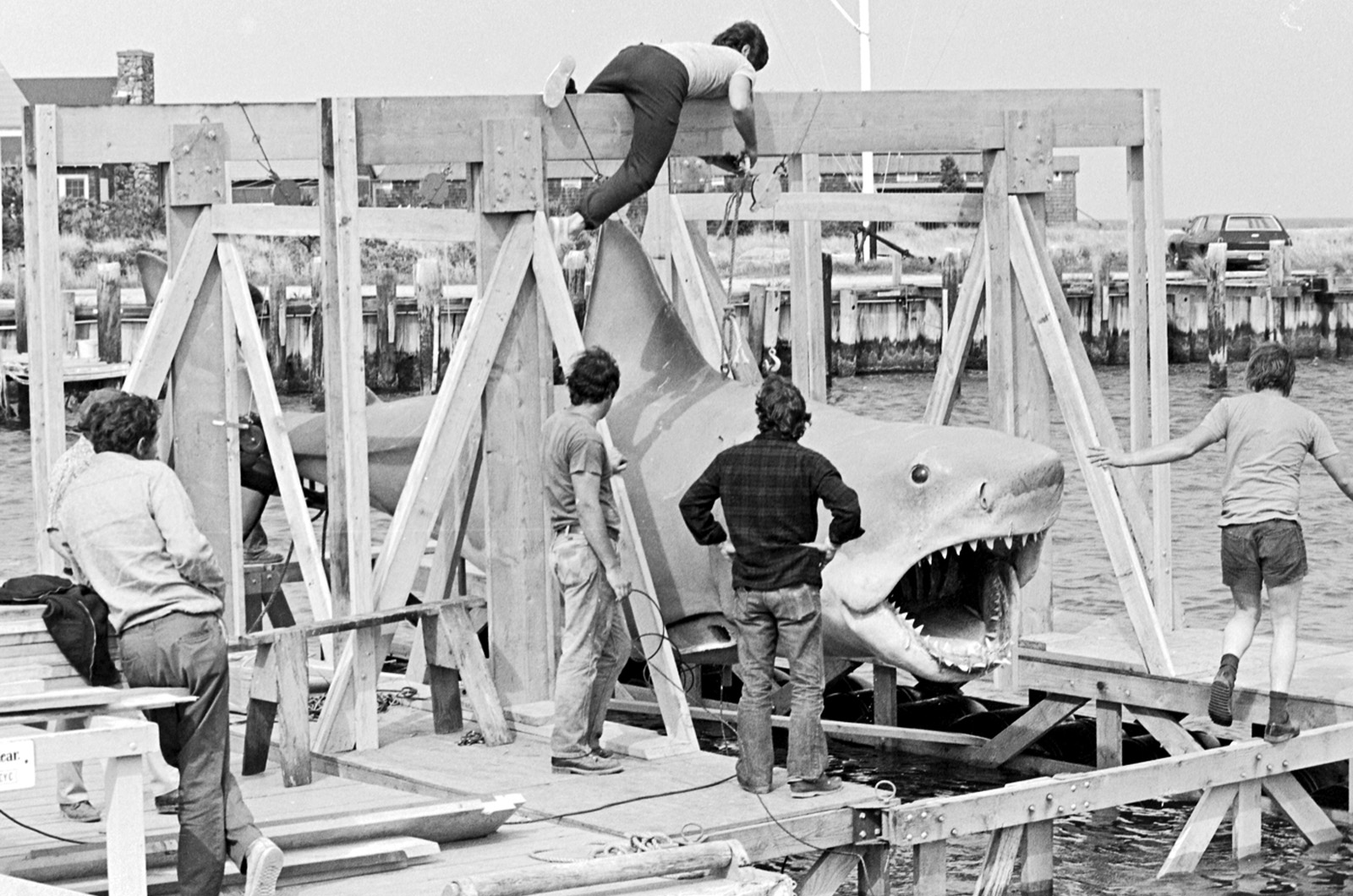

Along with local officials, dozens of Islanders and hundreds of extras got work onscreen, while Mr. Alves hired local workers to build his sets as a cost-saving measure for the studio.

“You generally take a crew to build sets, but it was such a low-budget picture they said ‘use locals, so you didn’t have to pay room and board,’ so I took just a painter and a carpenter and I hired all these guys that build boats,” he said.

Island officials had one major request for the filmmakers: Finish shooting before the summer season.

“We were supposed to be out of there by June [1974],” Mr. Alves said.

Instead, the production of Jaws became an element of Vineyard life for the entire summer and beyond, with local shops continuing to display Amity signs as the production team grappled with mechanical challenges from the untested shark.

Nicknamed Bruce, the Jaws monster was actually three machines: two toothy, full-frontal sharks, one with its left side open and one with its right side open to allow them to submerge rapidly, and a sled-like contraption with just a dorsal fin and tail for shots of the shark swimming near the surface.

“The problem we had is, the book came out in February [and] the studio said we want a summer release,” said Mr. Alves, who had only begun designing the shark in late autumn of 1973 and had expected to spend at least a year on the process.

“The shark didn’t get tested,” he said.

The balky shark is now credited with spurring Mr. Spielberg’s creativity, leading him to find new ways to scare his audience. But lingering on-Island into the summer months brought other complications, Mr. Alves said.

“When I scouted . . . in December, there were no boats. Come May and June, there were hundreds of boats,” he said.

This was particularly vexing when shooting the scenes aboard Quint’s fishing boat Orca, when the shark hunters are supposed to be cut off from all assistance after their radio is smashed.

“Steven was very, very firm that he didn’t see any other boats [in the shots],” Mr. Alves said. “He wanted them to be isolated.”

That meant pleading with countless boaters to keep clear of the watery set, he said.

“It took us so long to shoot the thing because we had to wait till the boats were out of the way,” Mr. Alves said.

“It was very difficult. Some people were very cooperative, other people weren’t.”

Looking back at the production, which he later chronicled in his illustrated book Designing Jaws, Mr. Alves expressed satisfaction at the film’s enduring success and said he’s looking forward to the 50th anniversary of its 1975 release.

“It all worked out pretty good, didn’t it?” he said.

Comments (27)

Comments

Comment policy »