Inside the Martha’s Vineyard Airport, a small exhibit displaying newspaper clippings, a flight suit and other naval artifacts reveals the airport’s military lineage. Eighty years ago, while World War II was raging in Europe, the military carved 683 acres out of the state forest to create the United States Naval Auxiliary Facility.

Though it was only in operation for four years, the base paved the way for the modern-day airport, which now sees more than 60,000 people passing through its terminal each year.

“We want to keep the history alive,” Geoff Freeman, airport manager and a self-professed history buff, said of the exhibit. “It is meaningful to remember the Island played a role in World War II.”

The Navy airfield, built in 1942 and 1943, was a subsidiary of a larger naval station in Rhode Island, and specialized in nighttime training for pilots looking to practice air carrier landings and takeoffs.

After the war, the base was given to Dukes County and eventually became the public airport that still serves the Island today.

The idea for a military base on the Island was first raised in 1941. State conservation officials came before the state legislature to ask for permission to lease the lands.

At the time, there was little to no development in the area, far from the Island downtowns. Despite the base’s isolation among the scrub oak, and the logistical headache of getting people and supplies to the Island, the Navy leased the land in 1942 for $1.

Not everyone was enthusiastic about the idea.

State Rep. Joseph Sylvia, who would later have State Beach named after him, introduced a bill to limit what the state could lease. Several letters to the editor and a Gazette editorial suggested there were mainland locations better suited to defending the country.

“The Island is not far enough offshore to serve as a defense base, and it is absurd to think that any base would be maintained here except as a temporary and wasteful measure,” the Gazette wrote in 1941. “But even such a temporary expedient could ruin the Island’s economics as well as its tranquility.”

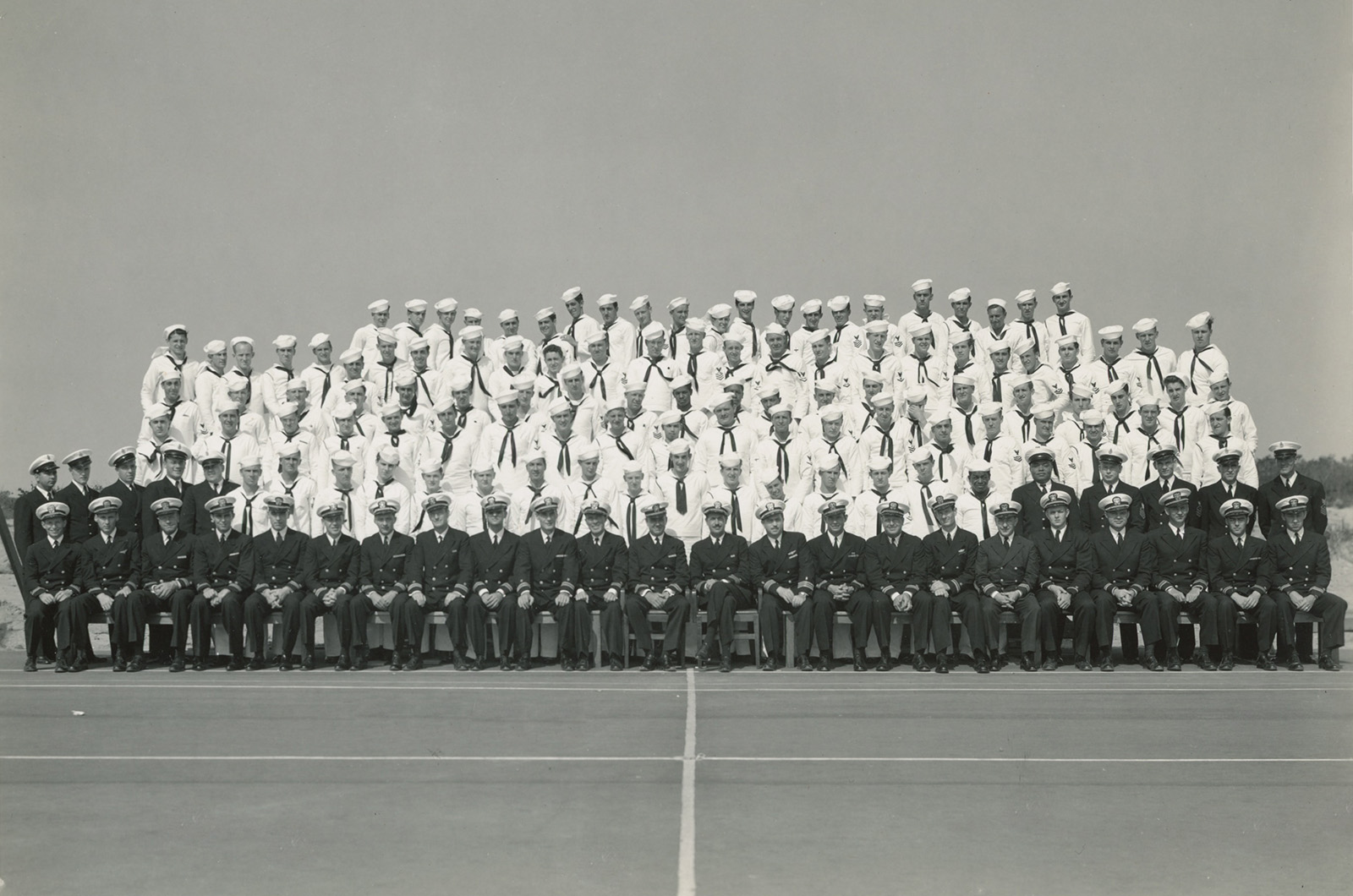

The project eventually went through, and by war’s end the airport would have three 3,700-foot-long runways, 21 squadrons and about 104 officers and 678 enlisted men.

In 1943 the airfield, later renamed the Naval Auxiliary Air Station, started to take shape in the public view. Where hawks, wildflowers and trees once dwelt, building materials emerged from trucks. Officer quarters, a mess hall, hospital, shops and a fire department were all built within a high barbed-wire fence. A water supply, pumping station and power plant were constructed around a central administration building.

“The field, in short, runs through the general catalog of a modern military airfield,” the Gazette reported in April 1943, while also calling it an “island within an Island.”

The activities on the base were largely kept quiet at the time for fear of tipping off the enemy.

“Soon the gray and silver war-birds will soar above the plain, and the contractors and their crews will be replaced by naval officers and men,” the Gazette reported as the base was being developed. “Those flights are what the Vineyard would like to read about. Well, so would Hitler, and that is why there is no mention of them here.”

But soon details began to emerge.

In December 1943, as the naval base was getting up and running, the Providence Journal did a large spread on the station. The report, complete with illustrations of the facility, noted the base was used for training and patrol work. Pilots in patrol planes would “sweep outward from this island to patrol the ocean highways where the commerce of war moves in ships.”

In 1945, the base had a change of mission. The “Night Attack Combat Training Unit-Atlantic,” helped pilots practice air carrier landings in the dark.

In an interview with Martha’s Vineyard Museum oral historian Linsey Lee for her 2011 book, Those Who Serve, naval officer Hector Asselin recalled his time stationed on the Island.

“I think the most we ever had at that base was something like 640 sailors. It was a very busy place,” he recalled. “We had the field, the inner field of the airport now, filled with planes lined up from these fellows flying them over. Everywhere you looked there was an airplane.”

The men stationed on the Vineyard seemed to find Island life pleasant, nicknaming the base the “Martha’s Vineyard Rod and Gun Club.” But training on the Island also proved deadly, with dozens of men perishing during training accidents.

“I remember all kinds of plane crashes,” Mr. Asselin said. “Oh, there was a lot of lives lost. We had night patrol squadrons go out and some planes never got back.”

By the end of the war, the moniker was changed to the “Martha’s Vineyard Blood and Guts Club.”

“It was mayhem out there,” local historian Tom Dunlop told the Gazette in 2019. “They either got lost in the fog, or there were collisions, or they just weren’t ready to do the maneuvers they were called upon to do.”

Following the war, the land and aviation facilities were leased to the county for use as a public airport, one of 64 airfields given up by the military. In 1946, the intention to give up the airfield was announced and airlines started to look into how they could fly to Boston and New York. The first civilian flight took place in 1945.

The county commissioners signed a 20-year lease for the property in June 1948. About 10 years later, the federal government, under the Federal Surplus Property Act, transferred all interest in the airport to the county.

The transfer ended debate about the potential of the airport being reclaimed by the Navy, potentially to use for training military jet pilots. Though there is only one remaining original building left from the war — a small storage building that can’t be taken down because of asbestos concerns — the original military base’s fingerprints are all over the Martha’s Vineyard Airport. The triangular runway layout from the air station is basically the same as today’s and the modern wastewater treatment facility stands where the crude Navy one was built. The old runways were only slightly shorter then, built to accommodate TBF Avenger and F6F Hellcat planes instead of the jets and commercial airlines of today.

Some remains of the past also emerge when work is being done on the property. There is a slight hump in the airport’s apron because of the old Navy hangar footing underneath it. During the area’s reconstruction in 2011, officials deemed that removing the footing would have been too pricey and time-consuming, and left it buried in the ground, Mr. Freeman said.

A foundation wall of an old hangar was also found where Vineyard Wind is building a helicopter hangar.

“Every once in a while, we’ll find some remnants of the old Navy structures,” Mr. Freeman said.

Many servicemen fell in love with the Vineyard during the war. Some, like Mr. Asselin, met their wives here, while others went home with memories of clambakes and pristine beaches.

“Servicemen who lived and worked at the naval air station and then survived the war returned here almost immediately with their young families for summer vacations, so taken with the Island were they during their training and service,” Mr. Dunlop said.

While commercial flights and private planes are commonplace today, the Martha’s Vineyard Airport still sees members of the armed services. C-130 cargo planes do drills here, Navy Hawkeye planes come to the Island to practice, and Presidential visits bring a host of government planes to the terminal.

Mr. Freeman said he’s proud to work somewhere that’s built on such a rich history and that he wants to carry on the tradition.

“It’s amazing to see what was built in 1942 as a Navy base is still somewhat true today,” said Mr. Freeman. “The Navy left us a valuable asset. We are continuing to grow and make it financially independent and a good opportunity for a gateway to the Vineyard.”

Comments (14)

Comments

Comment policy »