With six confirmed deaths from opioids in 2022, Martha’s Vineyard has not been spared from a crisis that is raging across the state. And now officials who work with people with substance use disorder are dealing with two new drugs that have hit the Island in recent weeks.

"The numbers are both disturbing and shaded by a new context,” said Brian Morris, a peer recovery coach at Island Health Care. “The [drugs] people want the most are things we aren’t ready for.”

Recently-released statistics show that Massachusetts had more than 2,000 opioid-related overdose deaths last year, a 2.5 per cent increase over the previous year. Though the Island only accounts for a small sliver of that figure, 2022 still counts as the second-highest number of overdose deaths going back at least 10 years. The previous high of seven deaths was in 2015.

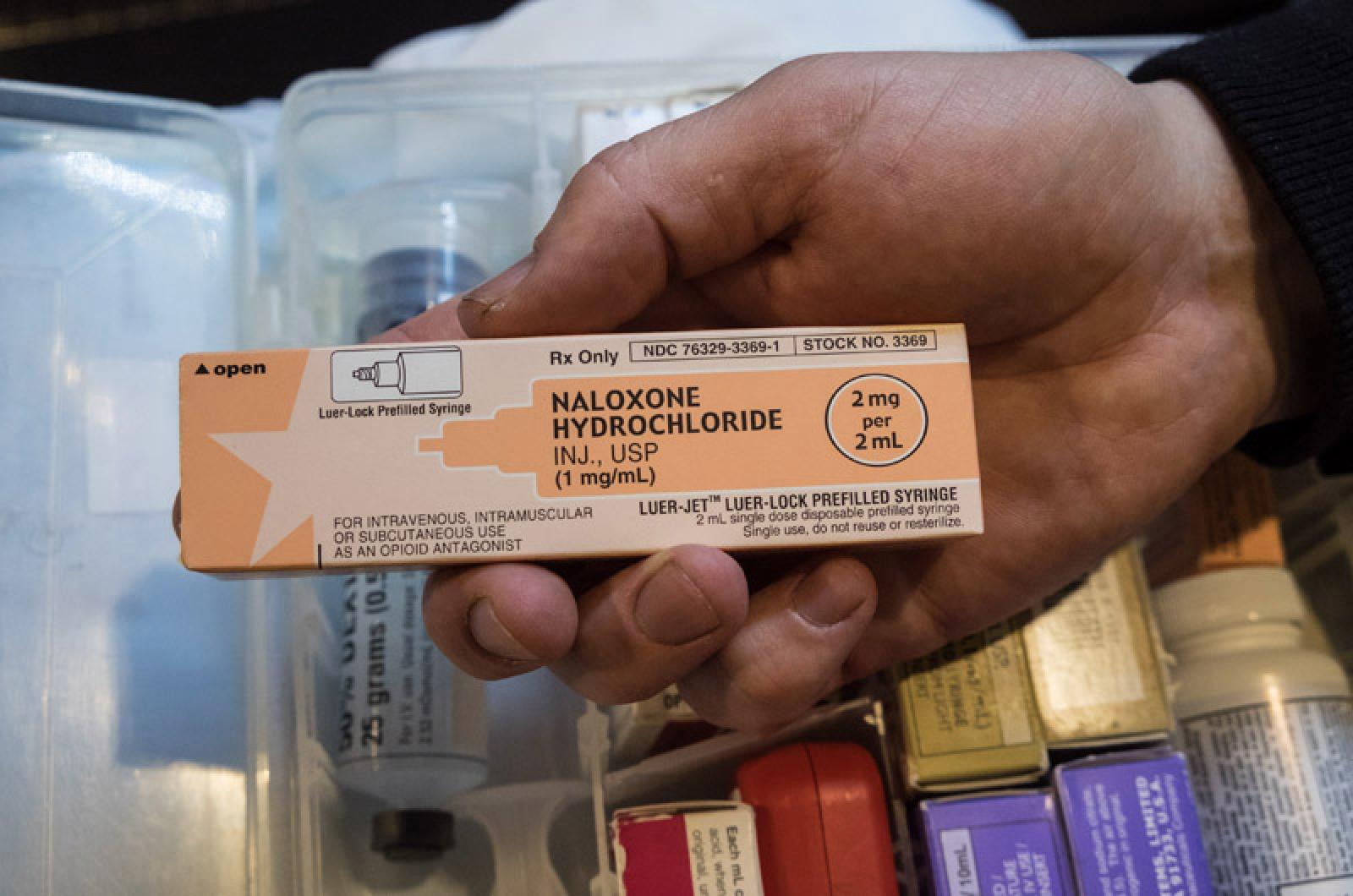

The high mortality rate persists even as the availability of the overdose-reversing medication naloxone has become more widespread. Ironically, that has made it harder to quantify the number of people struggling with opioid addiction since many people who overdose never come into contact with paramedics, police or hospital staff.

Naloxone, commonly known by the name Narcan — one of the name brands that produces the drug — has become increasingly easier to get. Once only carried by first responders, hospitals and other medical professionals, it is now available at several pharmacies across the Island and available for free from organizations that help people who use substances.

A standing order from the state that spreads a blanket prescription across pharmacies means people can get naloxone, which normally comes with two doses, without having to visit a doctor. Martha’s Vineyard Community Services provides the drug, as does the Red House, a peer recovery program on the Island.

This past weekend, Bill Rovero, the director of community initiatives at Community Services, had a few sets of naloxone at his table at the Tisbury Street Fair. One woman came up and took some in case a family member ever needed the overdose antidote.

“To see it sitting on our table, it didn’t raise any eyebrows of people walking by,” Mr. Rovero said.

Tisbury police Det. Charles Duquette said that, without question, there are more overdoses on the Island that go undocumented by the police and hospital, evidenced by the dozens of spent doses of Narcan he finds during some investigations.

“That to me is concerning,” he said. “It just kind of opens your eyes to how many people need it and nobody knows about it.”

The Tisbury police department responds to roughly about 10 overdoses a year, and Oak Bluffs police administered naloxone 15 times in 2022. Edgartown had four overdose calls in 2022.

Dr. Karen Casper, director of the hospital emergency department and the medical director of the substance use disorder program, said she believes many people on the Island who use drugs just aren’t coming to the emergency room or calling 911 for help as they did in the past.

In 2022, Martha’s Vineyard Hospital saw only four overdose cases in the emergency department, according to data provided by the hospital. That’s down from 2020, when the hospital had six cases.

“It’s a really hard data point to capture,” she said. “People have naloxone and they don’t call EMS.”

Both police and people who work with individuals with addiction say that as naloxone has become more abundant, drugs also have changed. When the opioid epidemic first took its grip on the Island, heroin was the most abundant opioid.

More recently, fentanyl, a more potent opioid, has become more prominent here, found in a plethora of other drugs.

“Everything’s fentanyl,” said Oak Bluffs police chief Jonathan Searle.

Tisbury’s Det. Duquette agreed, saying fentanyl ends up in everything from fake Percocet pills to cocaine.

“In the last couple years, there’s been an uptick in laced drugs,” he said.

And in the past several weeks, two new drugs have been seen on-Island.

Mr. Morris, the recovery coach at Island Health Care, has met people who have started using xylazine, an animal sedative commonly referred to as tranq that’s increasingly being mixed with fentanyl. The drug, which isn’t an opiate and is resistant to naloxone, can cause users to have gaping holes in their skin the size of tennis balls or larger.

“It’s here,” Mr. Morris said. “I dealt with it twice over the weekend.”

Mr. Rovero at Community Services and Stacy Wise, the outreach coordinator at The Red House peer recovery center, said tianeptine, an antidepressant commonly known as “gas station heroin” or “zaza” is also on the Island. They have had a couple cases involving the drug.

Tianeptine, which offers highs similar to heroin, isn’t approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, but isn’t technically illegal in Massachusetts and many other states, making it hard to stop.

“It’s concerning. We don’t know enough about it right now,” Ms. Wise said.

Despite a plethora of services on the Island, Mr. Morris said barriers persist for treating people with substance use disorder, including a lack of long-term recovery facilities or a detox on Martha’s Vineyard Any users wishing to enter detox have to cross Vineyard Sound for the mainland, creating a potential stumbling block. Portuguese speakers also have only three recovery coaches who can speak to them in their first language.

Mr. Morris said the Island has to remain dedicated to fighting drug addiction, no matter what the official overdose numbers say.

“Time’s up,” he said. “If we don’t treat it like a tsunami or a natural disaster… we’re dead meat.”

Comments

Comment policy »