Once largely isolated to the fringes of the Island, lone star ticks are spreading throughout Martha’s Vineyard, and health officials are advising extra vigilance to avoid the unpleasant consequences of their bite.

The ticks — known to cause the understudied alpha-gal syndrome that causes people to be allergic to beef, pork and other animal products — first started to pop up on the Vineyard about a decade ago.

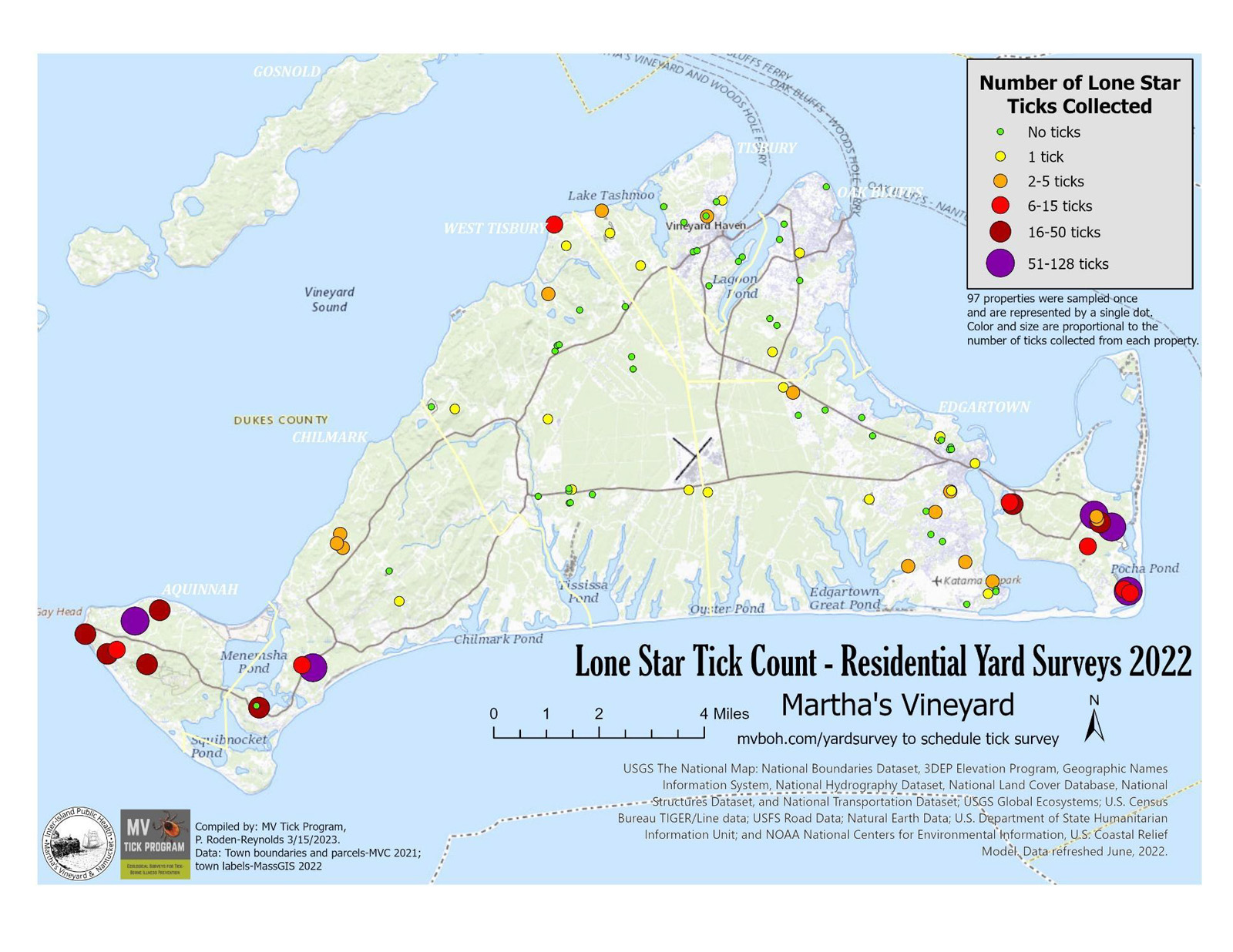

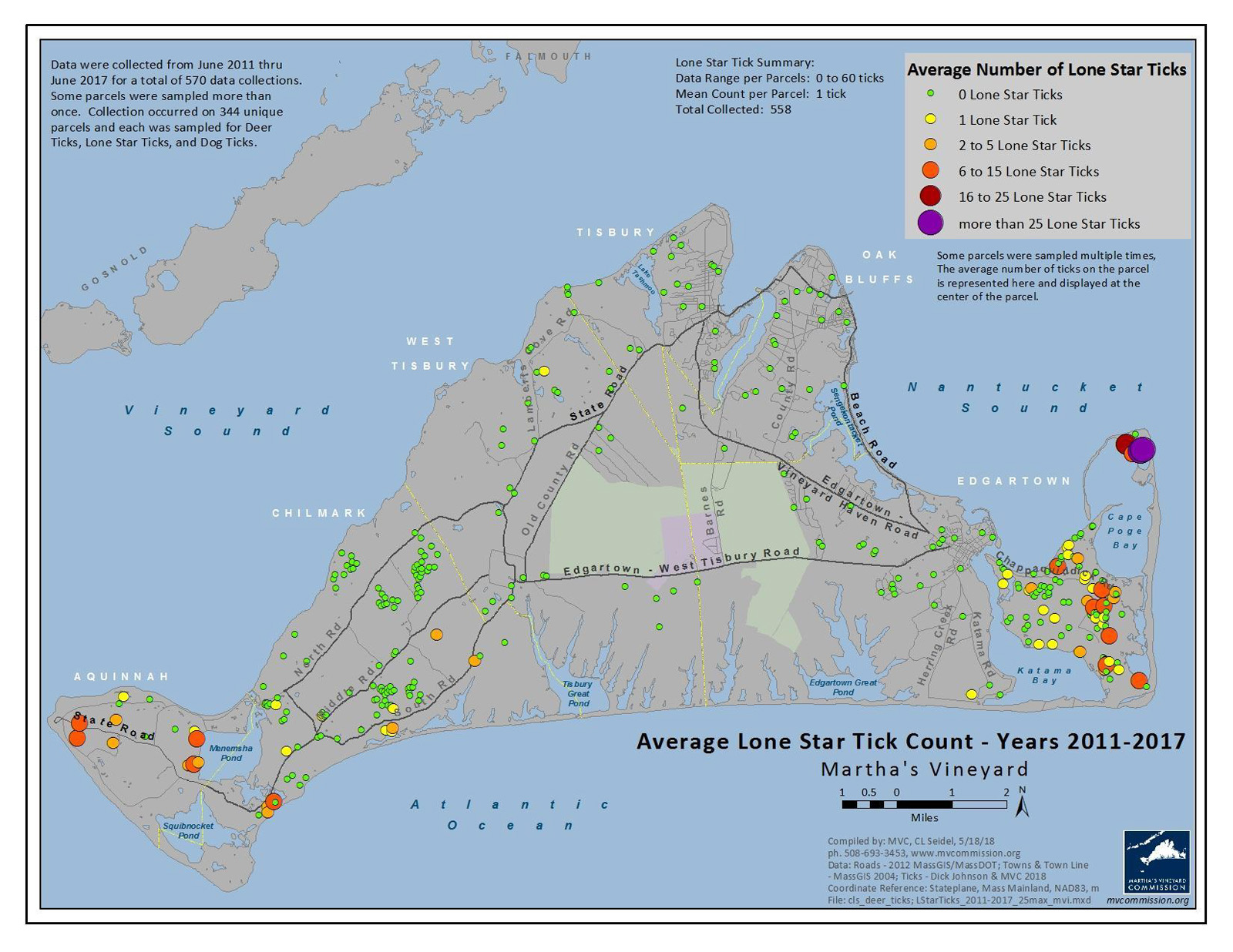

The tick’s Island epicenters have historically been in Aquinnah and on Chappaquiddick, but surveys done last year show the species is now found in all six towns, shattering the previous common belief that some towns were lone-star free.

“I’ve talked to people this last year. They assume if they live down-Island, they don’t have to worry about lone star ticks,” said Patrick Roden-Reynolds, the public health biologist at Island Health Care. “I just want to drive home the fact that we can find lone stars in all six of our towns here.”

Lone star ticks can trigger a severe allergic reaction to red meat, an affliction known as alpha-gal syndrome. Becoming more aware of the ailment, Island medical officials and residents report seeing cases of the syndrome rise in recent years as lone star ticks become more prevalent.

The Martha’s Vineyard Hospital lab tested 78 people for alpha-gal in 2021, and had 32 people test positive. In 2022, 165 people were tested and there were 79 positive cases.

As of mid-April, 17 people have tested positive in 2023. Four patients combined in 2021 and 2022 were tested twice.

“These positive alpha-gal results are confirmation that Martha’s Vineyard residents and visitors are at risk to tick-borne illnesses and should take precautions to avoid tick bites,” said Claire Seguin, the chief nurse officer at Martha’s Vineyard Hospital.

These numbers also don’t capture people who go elsewhere to get tested, or perhaps may never get tested at all. An allergist also warned that not everyone who tests positive for alpha-gal actually ends up allergic to meat, though they could develop the allergy if they are bitten by more ticks.

Because the illness is not an infectious disease, it isn’t tracked by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, making it hard to know how widespread the problem is.

One of the more worrisome things about lone star ticks is they, unlike deer ticks, actively find prey. While deer ticks lie in wait, hoping a victim will pass by, lone star ticks are fast moving and seek people out.

While people may have already been on alert for ticks because of the Island’s prevalence of Lyme disease, officials said the rise of lone star ticks may require even more vigilance and proactive steps.

The hospital recommended insect repellents with permethrin or DEET, wearing light-colored clothing to more easily spot ticks, and doing daily tick checks. Mr. Roden-Reynolds warned that pets can be a common way for humans to come in contact with lone star ticks.

Dick Johnson, who previously headed the Island tick-borne illness prevention program for about a decade, said people who are regularly outdoors should get their clothes treated with permethrin.

“People are really going to have to start wearing long pants with permethrin,” he said. “Just tucking the socks in without treating your pants isn’t as effective.”

The rise of lone star ticks on the Vineyard matches patterns seen on New York’s Long Island, where they have been a headache for years now. Though they are popping up in every town now, the largest concentrations on the Vineyard are still in Aquinnah and Chappaquiddick, where an average of more than 30 lone star ticks were found during surveys.

The ticks were first found in the southeastern U.S. but populations have sprung up northward as warming climates have made more places hospitable for them. The ticks, dubbed lone star because of the bright white spot on the back of adult female ticks, can lay thousands of eggs, making the spread of even a small number of females enough to establish a foothold.

In 2019, 11 surveys in Tisbury turned up 0 lone star ticks. As the head of the Island’s tick-borne illness prevention program, Mr. Roden-Reynolds did 14 surveys in Tisbury in 2022, five of which turned up the invasive arachnids.

“We found more ticks in yards in 2022 than in any other year in the past,” Mr. Roden-Reynolds said. “It’s not out of the question to come across one in Vineyard Haven now.”

Officials worry that the spread of lone star ticks will catch people off-guard this season and in the coming years.

West Tisbury had one survey in 2022 that turned up between six and 15 ticks, Tisbury had two that turned up as many as five ticks, and Oak Bluffs had two surveys that turned up one lone star tick.

“They are in all six Island towns and they’re only going to increase,” Mr. Johnson said. “It’s going to be a real shock to people in the next five years or so.”

Mr. Johnson said he personally knows of at least 35 people on the Island with alpha-gal syndrome. He advocated that Islanders start to collect more information themselves to get a handle on how widespread the alpha-gal is.

“We do need to have a registry,” he said. “There’s got to be an awful lot of people out there. We’re trying to get some idea of how common it is.”

Erin McGintee, an allergist who has treated hundreds of people with alpha-gal on New York’s Long Island, also said she believes that lone star tick larvae, the miniscule baby ticks that are found by the hundreds in nests, can cause the meat allergy.

Ms. McGintee told this to a room full of Vineyarders when she was the guest speaker at an alpha-gal talk hosted by the MV Tick Prevention Program last month.

“I see it all the time,” she said. “They’re the worst.”

It was a startling development for some attendees who previously thought only older, larger and easier to spot lone stars cause the syndrome.

“That was a bit of a shock to me,” Mr. Johnson said.

Comments (10)

Comments

Comment policy »