As coastal ponds and estuaries continue to deteriorate throughout the Cape and Islands, the state Department of Environmental Protection has proposed a pair of wastewater regulation amendments that could have sweeping impacts across the region, forcing Island towns to upgrade hundreds — if not thousands — of septic systems, or come up with a long-term plan to mitigate their nitrogen pollution.

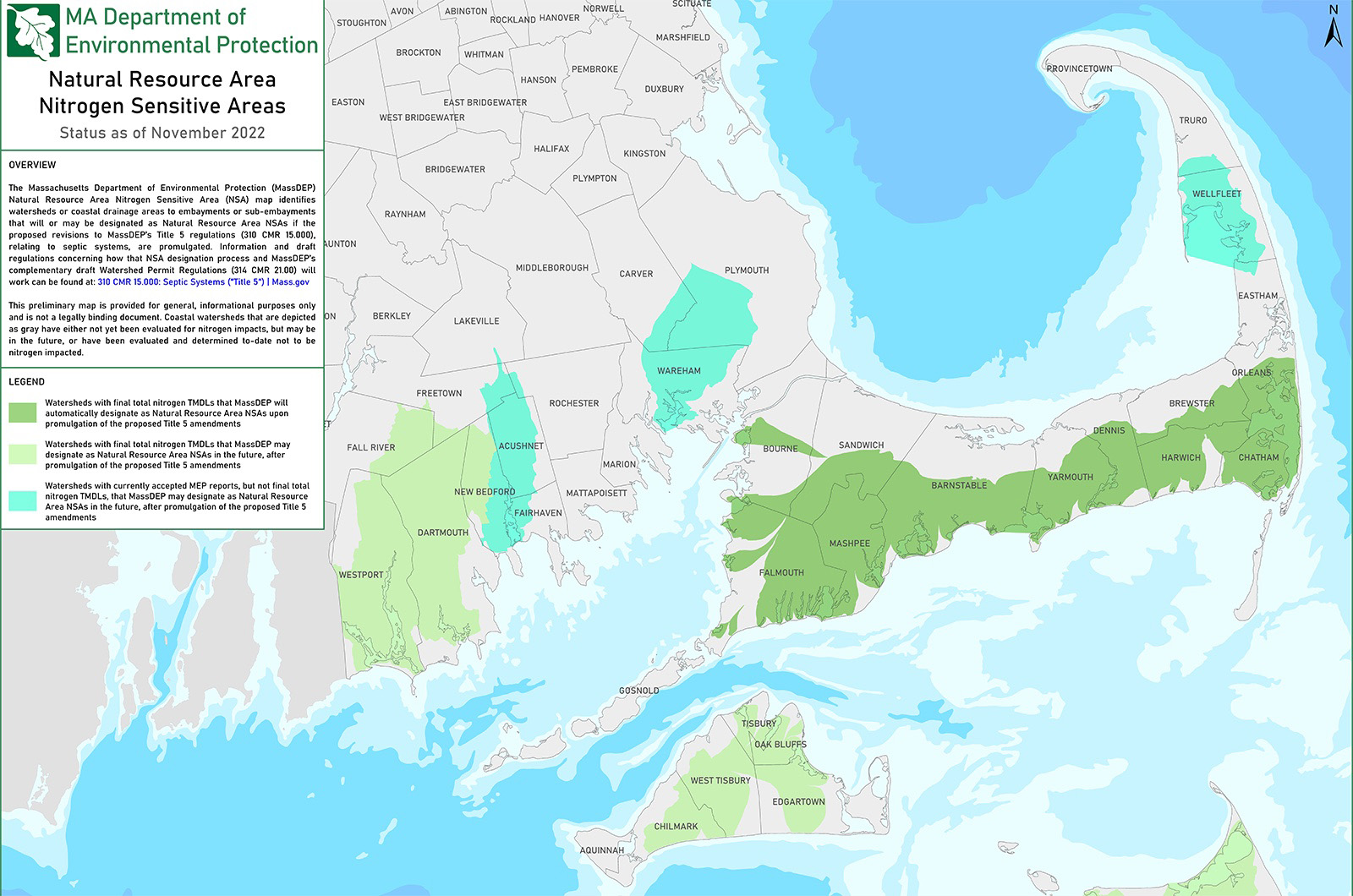

The proposed Title 5 amendments, which constitute the most substantial changes to the state septic code since it went into effect in 1995, are twofold; the first amendment involves designating coastal communities that have been polluted by nitrogen runoff as “nitrogen sensitive areas.” The second would require the installation of enhanced septic systems on all new and existing properties within those sensitive areas in five years — a massive undertaking that would cost tens of millions of dollars.

Communities may be exempted from the second part of the regulation, however, if they apply for a watershed permit, giving them more flexibility in developing a 20-year plan to address nitrogen pollution.

Although the regulations would only immediately apply to particularly impaired communities on the Cape, areas of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket would likely follow quickly thereafter, state DEP commissioner Martin Suuberg explained in a letter that went to affected towns earlier this year.

While the final regulations are still being hammered out in a public hearing process that began Wednesday, Nov. 30, Island officials are already bracing for the regulations’ impacts.

“It’s bigger than anything that’s happened with on-site wastewater in Massachusetts ever, period,” said Matt Poole, Edgartown health agent and elected member of the Chilmark board of health. “It’s a big increase in [the board’s] daily septic and wastewater activity, and we already do a lot.”

The proposed Title 5 amendments come in response to decades of nitrogen pollution leading to ecosystem disruption on the Cape and Islands, and follow closely on the heels of a Great Ponds Foundation study this summer that identified septic waste as the primary nitrogen polluter in the Island’s great ponds.

Because of the rural nature of much of the Island, most homes rely on septic systems rather than town sewers to handle water from toilets, showers, dishwashers, sinks and laundry machines. But the runoff from those septic systems can seep into the Island’s sandy soil, making its way into ecologically-sensitive coastal ponds and damaging the ecosystem.

“Densely populated areas have resulted in more nitrogen loads than these water bodies can accept,” said Marybeth Chubb, head of the MassDEP wastewater management program, at a public information session on Nov. 15. That nitrogen, she explained, can lead to a process of eutrophication in the ponds, causing excess algae growth, oxygen depletion and the death of fish, shellfish and eelgrass.

“Unaddressed, this problem will become worse,” Ms. Chubb said.

If the regulations are adopted, Ms. Chubb explained, they would immediately go into effect in Cape Cod communities designated as nitrogen-sensitive areas, aiming to reduce nitrogen pollution in their watersheds by upwards of 75 per cent. Chilmark, West Tisbury, Oak Bluffs, Tisbury and Edgartown all have areas that could be designated as nitrogen sensitive after the regulations are promulgated, meaning all five towns could be subject to similar restrictions following their enactment on the Cape. Each Island designation would be subject to its own public hearing process before restrictions were put in place.

Towns on the south shore, including Westport, Dartmouth and New Bedford, could also be designated as nitrogen sensitive. At Wednesday’s public hearing, public officials from the region blasted the state for failing to address nitrogen pollution, and instead passing the buck onto towns or homeowners.

“It’s basically death by a thousand cuts with lemon, or death by a thousand cuts with lime,” said Dartmouth select board member Shawn McDonald.

The move to update the regulations follows a 2021 lawsuit from the Conservation Law Foundation, claiming that the state DEP, as well as the towns of Mashpee and Barnstable, knowingly neglected their obligation to halt pollution-causing septic systems in those areas. The new regulations function as a compromise, pushing towns to either upgrade septic systems fast, or devise a plan to deal with them broadly down the road.

“It’s the carrot and the stick approach,” said Doug Cooper, who owns a business that does Title 5 septic inspections on the Island. In an interview with the Gazette following a septic inspection, Mr. Cooper said that updating septic systems to include enhanced nitrogen mitigation technology can be a complex and invasive process.

“Some systems are fairly easy to upgrade, and some are a bloody nightmare. Imagine a car where you’re adding in a turbo charger . . . you’re gonna be pulling up wires and hoses everywhere,” he said, referring to the need to dig up large portions of a homeowner’s yard to put in the upgrade. Other systems, he added, weren’t fit for upgrade, and would need to be replaced wholesale.

The upgrades are also expensive, costing anywhere from $30,000 to $50,000 each. Mr. Poole estimated that upgrading all of Ocean Heights, which is in the Sengekontacket watershed, could cost up to $25 million, a burden he said would ultimately fall on the town via a financing plan mandated by MassDEP; at the public hearing, speakers also expressed concern over the financial burden on homeowners, particularly because financing could be too expensive for towns alone. “Financially, I don’t think Edgartown, or any of the other towns on the Vineyard, can do the five-year option,” he said.

As a result of the cost and involvement it would take to upgrade all those systems, Island towns are initiating plans for a watershed permit.

“Five years is just too fast to get it done,” said Tisbury health agent Maura Valley.

Ms. Valley believes that Tisbury is well situated to meet the new state requirements, since it already has more stringent nitrogen regulations than other Island towns. However, Tisbury’s sensitive Lagoon Pond watershed points to another challenge towns may face: collaboration.

Lagoon Pond, like Sengekontacket and the Tisbury Great Pond, straddles two towns, and will require joint management to meet new regulations.

“It’s not clear to me, on the state level, how shared watersheds will work,” said Ms. Valley. “But from an Island perspective, we will have to work with the other towns.”

All three down-Island towns have an advantage in developing their watershed permit, as each has already begun working on a comprehensive wastewater management plan (CWMP). Critically, CWMPs will inform the health boards as to the current and planned future sewer capacity in the town; every sewer-connected lot represents one less property that has to be put on septic. Mr. Cooper suggested that smaller wastewater processing facilities for dense areas, such as the one at the Aquinnah tribal housing, might be another possible option.

For the up-Island towns, health agents are considering a whole different set of options.

“I can’t get my head around what Chilmark’s solution might be like as easily,” said Mr. Poole, who is recommending that Chilmark hire an environmental consultant to help with the process. “We want to have someone that’s not gonna be outgunned when they’re at the table,” he said.

West Tisbury health agent Omar Johnson also said he planned to recommend a consultant.

“It’s a huge, huge project,” he said.

The regulations will also have broad implications for town planning, said Mr. Cooper.

“Historically, the Island had mostly controlled growth through the health and septic code,” he said, meaning that towns will also need to think critically about how to modify their growth and development policies as septic regulations change.

Still, there is hope among health officials that the Title 5 update will have a major benefits for at-risk, stressed Island water resources.

“Time will tell as to what the regulations will look like,” Oak Bluffs health agent Garrett Albiston said. “But it’s going to be positive for the towns and the quality of water on-Island.”

The state will hold its final public hearing on the changes over Zoom on Dec. 5 at 6 p.m. Written comments will be accepted through Dec. 16.

Comments (33)

Comments

Comment policy »