Driving While Black: Race, Space and Mobility in America, the newest documentary by filmmaker and seasonal Chilmark resident Ric Burns, is now airing on PBS stations and streaming on the broadcaster’s website.

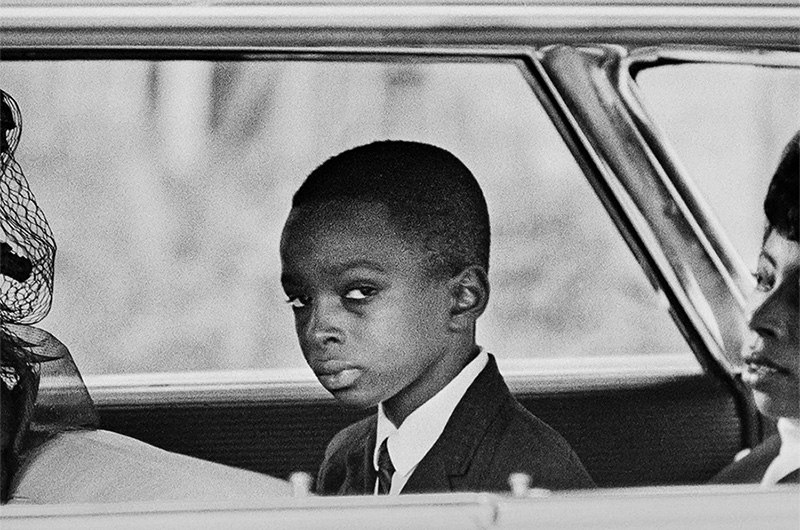

While the film’s title comes from current events, the arrests, beatings and shootings of unarmed black motorists in 21st-century America form only part of its wide-ranging narrative, which argues powerfully that black mobility has always faced resistance here.

“The point of the film is that there are roots to this, and that one must understand those roots,” Mr. Burns told the Gazette this week, by phone from New York city. “You can’t simply take things, hideous moment by hideous moment, and just reel with the unbearable pain of that, because it doesn’t come out of nowhere.”

Mr. Burns co-directed the film with Gretchen Sorin, author of the book Driving While Black: African American Travel and the Road to Civil Rights, who also appears on-screen. With Mr. Burns’s longtime collaborators Emir Lewis — a seasonal Oak Bluffs resident — and composer Brian Keane, the directors have woven a compelling history using vintage images, films, texts, music, interviews with contemporary scholars and the occasional animated illustration.

“History is not illegible,” Mr. Burns said. “It may be complex, but it’s not magic and it’s not abstract and it’s not invisible. Once someone shows you how to see it, which is what Gretchen and her colleagues have done, you can never unsee it.”

While building its devastating argument that America has limited black people’s freedom ever since slaves were packed into ships bound for the colonies, the documentary has bright moments as well. Old photos and home movies give viewers a taste of the joy black families felt when their automobiles freed them from segregated train travel.

“The access of freedom which all Americans felt was felt especially vividly by African Americans,” Mr. Burns said.

In one of her last interviews before she died at 96 last year, famed Creole chef Leah Chase recalls the heyday of black motor guides like the Green Book, which listed businesses where black travelers could safely shop, eat and stay in the segregated U.S.

Another appealing sequence visits black resorts, including Oak Bluffs.

“The carving out of Oak Bluffs as a space of refuge for African American vacationers is a crucial historic part of this story,” Mr. Burns said.

Automobiles also propelled the civil rights movement, allowing black and white activists to meet and travel together from town to town.

“The African American civil rights activists and their white accomplices are getting around by car,” Mr. Burns said. In the film, Ms. Chase recounts sheltering them at her New Orleans restaurant, Dooky Chase’s.

“The Freedom Riders — they made the plans right here in this restaurant,” Ms. Chase recalls. “This was a safe haven for all of us.”

Against these uplifting scenes, the filmmakers weigh an array of direr consequences.

Once the Civil Rights Act banned discrimination at businesses in the mid-1960s, travel guides stopped publication and many of the black-owned tourist establishments went under. Others were bulldozed for interstate highway construction, which slashed through minority neighborhoods.

And traveling itself has remained risky for black motorists, as dash-camera and bystander recordings have increasingly revealed. In multiple interviews, black parents reflect on the need to tell their children how they must behave during a police stop if they want to survive.

“White Americans cannot understand the gut-wrenching horror that is driving in a racist society,” Pasadena City College professor Christopher West tells the filmmakers.

Mr. Burns hopes the documentary will spur more people to recognize, and oppose, the persistence of racist enforcement.

“This is not an anti-police film,” he said. “We need our police. They are the foundations of our community.”

But, the film argues, modern policing still has roots in Southern slave patrols and Jim Crow policies controlling where black people could be and go.

“Nothing fills me personally with greater rage and dismay than the idea there is no such thing as systemic, structural racism,” Mr. Burns said. “This history, like all history, is a call to action. If you see it, now you know what’s going on, and then you have to say ‘What will I be doing in relation to this?’”

Island moviegoers got an early look at Driving While Black, as work in progress, at an August, 2019 screening by the Martha’s Vineyard Film Festival that included a question and answer session with Mr. Burns and Mr. Lewis.

“I was so proud of the Vineyard. I was so moved,” Mr. Burns said this week. “In the history of the unfolding of this film, that night was transformative for the filmmakers. Man, did we double down on our commitment to what we were doing.”

Mr. Burns said the next project he and Mr. Lewis are working on is about the 14th-century Italian poet Dante Alighieri, author of the Divine Comedy.

The ninth episode in his PBS serial New York: A Documentary Film is also in the works, he said.

“There’s a lot that’s keeping us busy these days,” Mr. Burns said. “I feel privileged.”

Comments (4)

Comments

Comment policy »