Is there ever too much of a good thing? I don’t want to believe it to be true when it comes to peas, a spring favorite.

Emily Dickenson and Winston Churchill were two peas in a pod when it came to their predilection for the pea. In her poetic prose, Dickenson romanced the legume: “How luscious lies the pea within the pod.”

Churchill was more upscale, even if he claimed an unassuming lifestyle: “We lived very simply — but with all the essentials of life well understood and provided for — hot baths, cold champagne, new peas and old brandy.”

But, yes, it is possible to have too much of good thing if that thing is wild peas. Breathe a sigh of relief — I said wild peas, which means you, along with Emily and Winston who both showed little restraint, can eat garden peas to your heart’s delight.

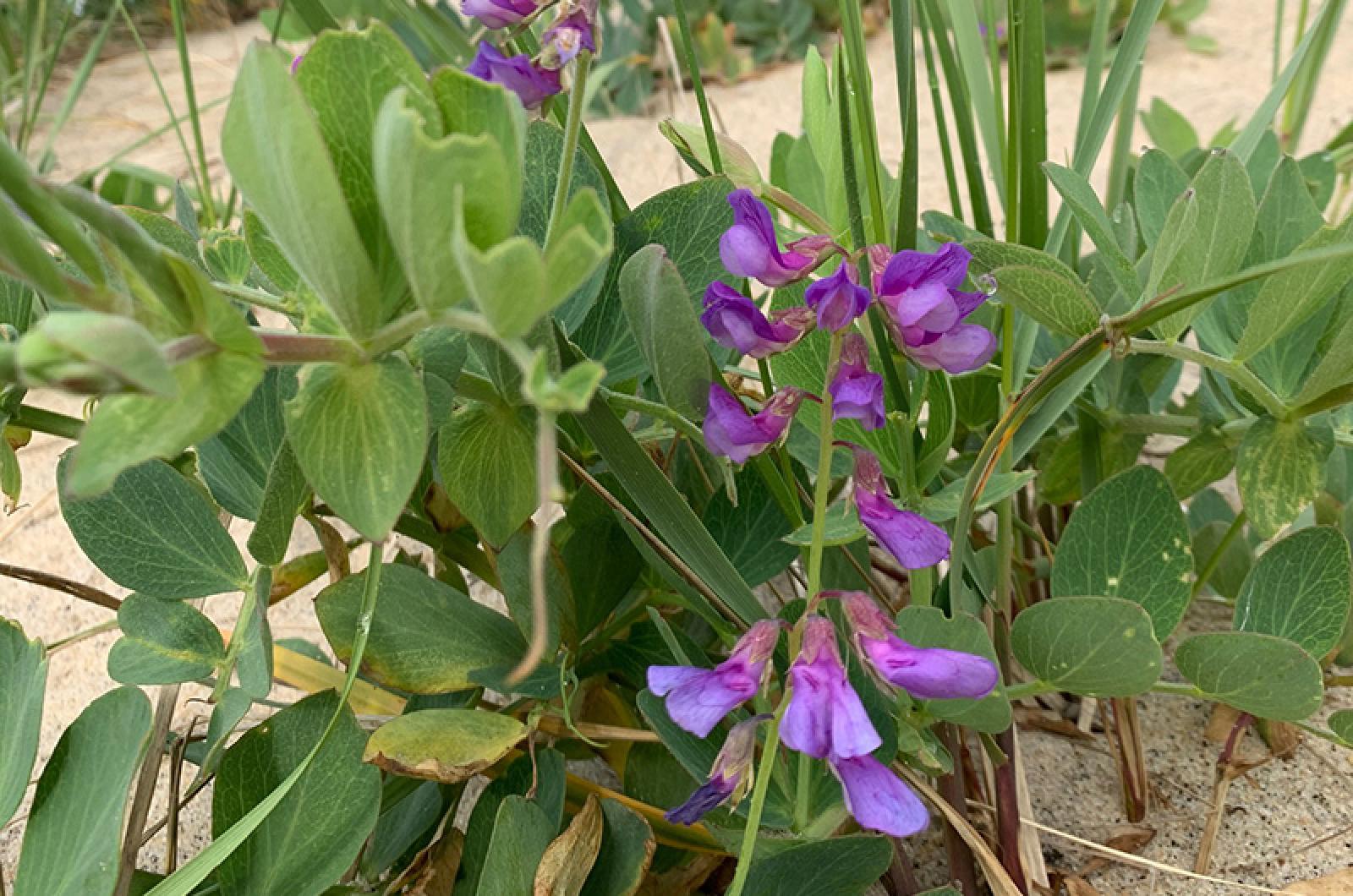

Wild peas, however, are a different story. One common species, beach peas (Lathyrus maritimus), are blooming purple on dunes and amongst our sandy shore vegetation. This plant, also called sea peas, circumpolar pea, and sea vetchling has long provided beauty and nourishment. Much of the plant, including the young shoots and leaves, the tendrils, the seeds (peas), and even the fresh undeveloped pods, can be consumed.

For wild peas of some varieties, extreme excess can be deadly. What is the magic number for wild peas and why can’t you eat them until you turn green? The magic number, it turns out, is 30 per cent. Experts say that if 30 per cent of your diet is wild peas over at least a few months, you could get sick and even become crippled from a toxic compound in these plants.

The culprit, like a heaping spoonful of peas, is a mouthful. Oxalyldiaminopropionic acid (ODAP) is a toxic amino acid that is found in plants in the genus Lathyrus. It acts as a neurotoxin that causes a muscle-wasting disease called lathyrism, which results in severe paralysis in otherwise healthy people.

This condition can result from the overconsumption of species of peas in the genus Lathyrus, but luckily it is not common in this country due to the difficult and unusual circumstance of eating that many legumes and little else. And even better for us Vineyard pea lovers is that this nutritional disorder is more common in Asia and East Africa and generally contracted by eating a different type of peas than our local variety.

With a sigh of relief, we can turn back to the pea possibilities. Ewell Gibbons suggested savoring the peas with a tablespoon of coffee creamer and black pepper after cooking them in boiling water. He recommended eating them piping hot, as they “become uninteresting when cold.”

Local chef Cathy Walthers and herbalist Holly Bellebuono single out the tasty tendrils, and I am enticed to harvest the young leaves and shoots.

No matter how you prefer your peas, remember to enjoy responsibly. In the wise (and paraphrased) words of John Lennon, all we are saying is give peas a chance.

Suzan Bellincampi is director of the Felix Neck Wildlife Sanctuary in Edgartown, and author of Martha’s Vineyard: A Field Guide to Island Nature and The Nature of Martha’s Vineyard.

Comments

Comment policy »