The rapid and unexpected expansion of the lone star tick into New England is partially caused by climate change and poses an ominous public health risk for coastal communities like Martha’s Vineyard, according to a recent paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

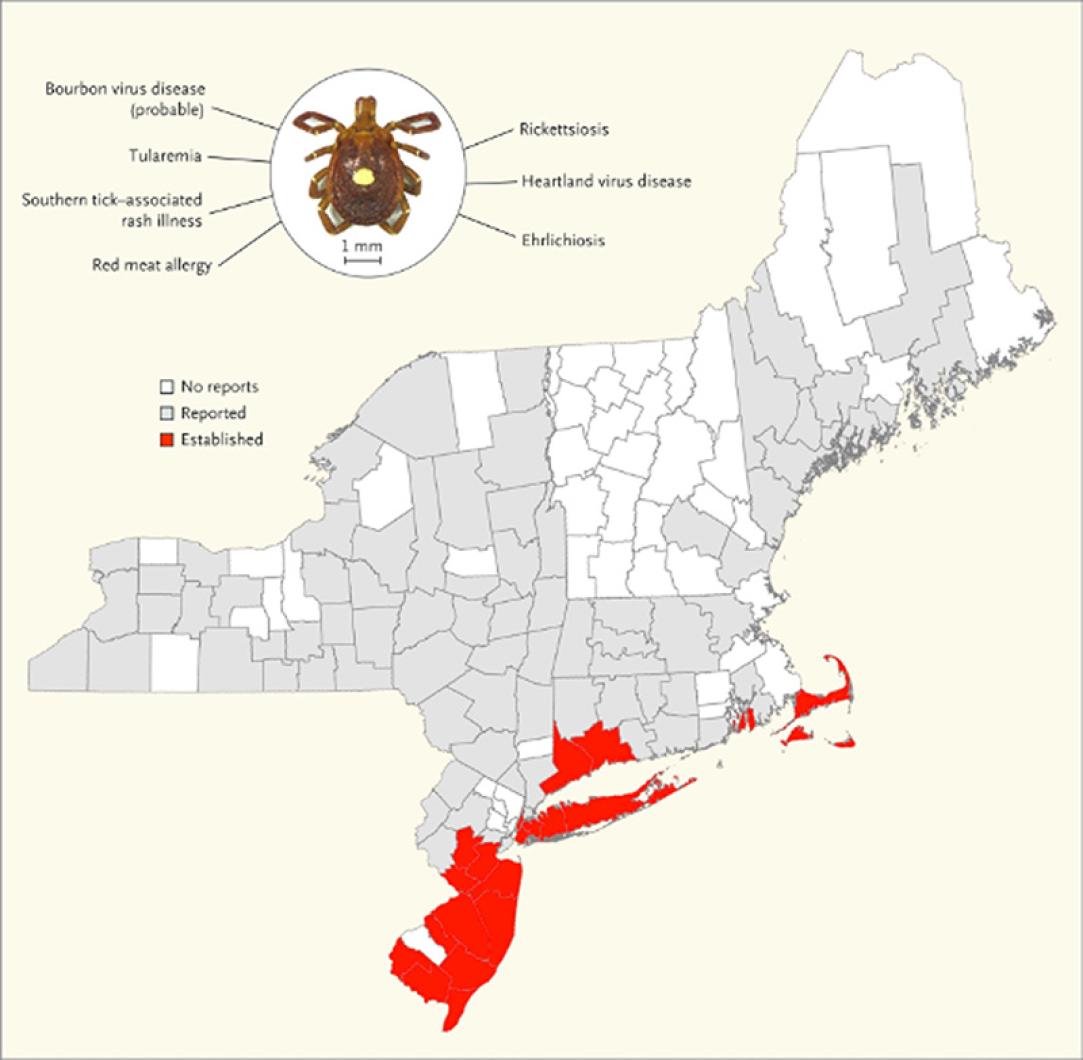

Historically confined to the southern United States, lone star ticks now have established breeding populations in New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Cape Cod, Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard, among other locations. Most of the dreaded, white-dotted arachnid’s spread into the region has occurred over the last two decades, throwing fragile ecosystems into flux and leaving the medical community on its heels.

“This tick is rapidly expanding its range of distribution,” said Dr. Goularz Molaei, the lead research scientist on the paper who spoke with the Gazette by phone. “You can call it ‘lone star rising,’ how about that?”

In the last decade, Mr. Molaei, the director of passive tick surveillance at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Association and associate clinical professor at the Yale School of Public Health, has seen the percentage of lone star ticks that come to his laboratory for testing increase 16-fold, from 0.2 to 3.2 per cent of the state’s total tick population. A similar expansion has occurred on the Vineyard, where yard surveys conducted by the tick-borne illness reduction program have revealed a proliferation of lone star ticks on Chappaquiddick and up-Island over the past five years.

According to program director Dick Johnson, 20 out of 20 homes surveyed in Aquinnah this past summer had lone star ticks on their property. On Chappaquiddick, where they first arrived on the Island, all 58 properties surveyed had lone star ticks. And for the first time this year, lone star ticks were found in yards in Oak Bluffs as well.

“The spread is continuing,” Mr. Johnson said. “We are seeing lone star ticks in more places and in higher numbers in places where we are finding them. It just keeps getting worse.”

Identified by the eponymous white dot on the back of adult females, lone star ticks are the only one of the region’s three main tick species (deer ticks and dog ticks are the other two) that feed on deer during all three stages of their life cycle. Although they have been present on the Island for decades, the recent population explosion is linked to a combination of biotic and abiotic factors, including the resurgence of deer and wild turkey populations, reforestation and a warming climate, the Journal of Medicine article states.

And since lone star ticks can lay several thousand eggs at a time, even the dispersal of a small number of gravid, or egg-carrying females, could be enough to establish populations in areas with large deer populations and moderate maritime temperatures — all of which the Vineyard satisfies.

“Abundant reproductive hosts, an increasingly hospitable climate, and genetic plasticity of the lone star tick support the continued invasion and establishment of this tick in the Northeast,” the Journal of Medicine article concludes. “Increasing population densities and subsequent range expansion, in conjunction with nondiscriminating biting habits and the capacity to transmit diverse pathogens, position the lone star tick as an important emerging health threat to humans, domesticated animals, and wildlife. It’s also plausible that the lone star tick will displace local tick species, transmit different pathogens than those species, and alter the tick-borne disease landscape.”

According to Mr. Molaei, it is unknown how the invasion of the lone star ticks will affect the current population of deer and dog ticks on the Island. In southern habitats, the lone star tick has been shown to compete with, and ultimately replace, dog tick populations. Mr. Johnson said that has not yet occurred on the Vineyard.

The threat of a changing landscape for ticks, and the diseases they carry, poses new environmental challenges for the region and new scientific challenges for its medical community. Mr. Molaei said that only 10 to 50 per cent of doctors in Connecticut can identify ticks by species, and that a large percentage of those doctors did not know what diseases were transmitted by each individual tick.

While lone star ticks do not transmit Lyme disease, they can serve as vectors for a number of nasty pathogens, including a spotted fever called Erhlichiosis, a different febrile disease called Rickettsia amblyommii, STARI and the feared red-meat allergy recently connected to tick bites.

“Can the lone star claim victory and start transmitting its own diseases that are different than Lyme disease?” Mr. Molaei asked. “If [that] is the case, we don’t know what is going to happen to the dynamics of tick borne disease throughout the region . . . If [doctors] don’t know what the tick species is, this is a major problem.”

Vineyarders have already confronted these challenges, as doctors on the Island have been forced to diagnose patients on the frontier of the lone star invasion. According to Mr. Johnson, there has been a large increase in the number of reported cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever on the Island, from two in 2018 to 25 this year. Because many of the symptoms are difficult to distinguish from a rare spotted fever transmitted by lone star ticks, he believes the increase in lone star population could be a cause for the high spotted fever numbers.

Throughout the region, Mr. Molaei called for a greater reliance on active tick surveillance that looked explicitly for lone stars, similar to the work being done by the Vineyard’s tick reduction initiative, and emphasized technology for a deer feeding post that releases permethrin when the animal rubs against it.

Currently there is also legislation before Congress called the Kay Hagan Tick Act that would establish a federal office for vector-borne diseases as well as regional centers of excellence that focus on tick-borne illness prevention. It would allocate $30 million per year through 2026 to launch the initiative and begin to adopt strategies for combating tick-borne illness. The act is named after former North Carolina Sen. Kay Hagan, who died this past year from complications of Powassan virus, which she contracted from a tick bite. Although Mr. Molaei said the developments were promising, he said coastal communities in the Northeast should brace for the worst.

“We are at the early stages of this taking over and establishing population, and unfortunately we don’t have much resources to deal with this tick,” Mr. Molaei said.

Mr. Johnson was hopeful that increased awareness regionally, and at the national level, would help leverage funding for an issue Vineyarders have known all too well.

“It’s been seen as a somewhat localized problem,” Mr. Johnson said. “I think it’s finally going to get people’s attention that these ticks are spreading and it’s not just a local problem anymore, and they are going to bring their diseases with them. With so many people now affected, maybe it will spur more action, which is important.”

Comments (10)

Comments

Comment policy »