My sister Lisa is not a flea markets fanatic, but she did come across an interesting find while rummaging around on the internet. She called to ask if I knew that flea circuses were an actual thing.

She was itching to share her new knowledge of this phenomenon. She explained that flea circus isn’t just an expression — there was a time when these bugs were the price of admission — there were real flea circuses with real performing fleas.

My first thought was that Lisa, who works from home, was spending too much time by herself. Once I jumped into the world of circus fleas, though, I too was fascinated.

The origin of flea circuses begins with a blacksmith named Mark Scalliot. He created a miniature lock and extended chain and attached it to a flea — mostly to show off his metal-working skills. Putting the chain around the neck of a flea, he created wonderment at the minimal weight and maximum skill needed to create so small a work of art.

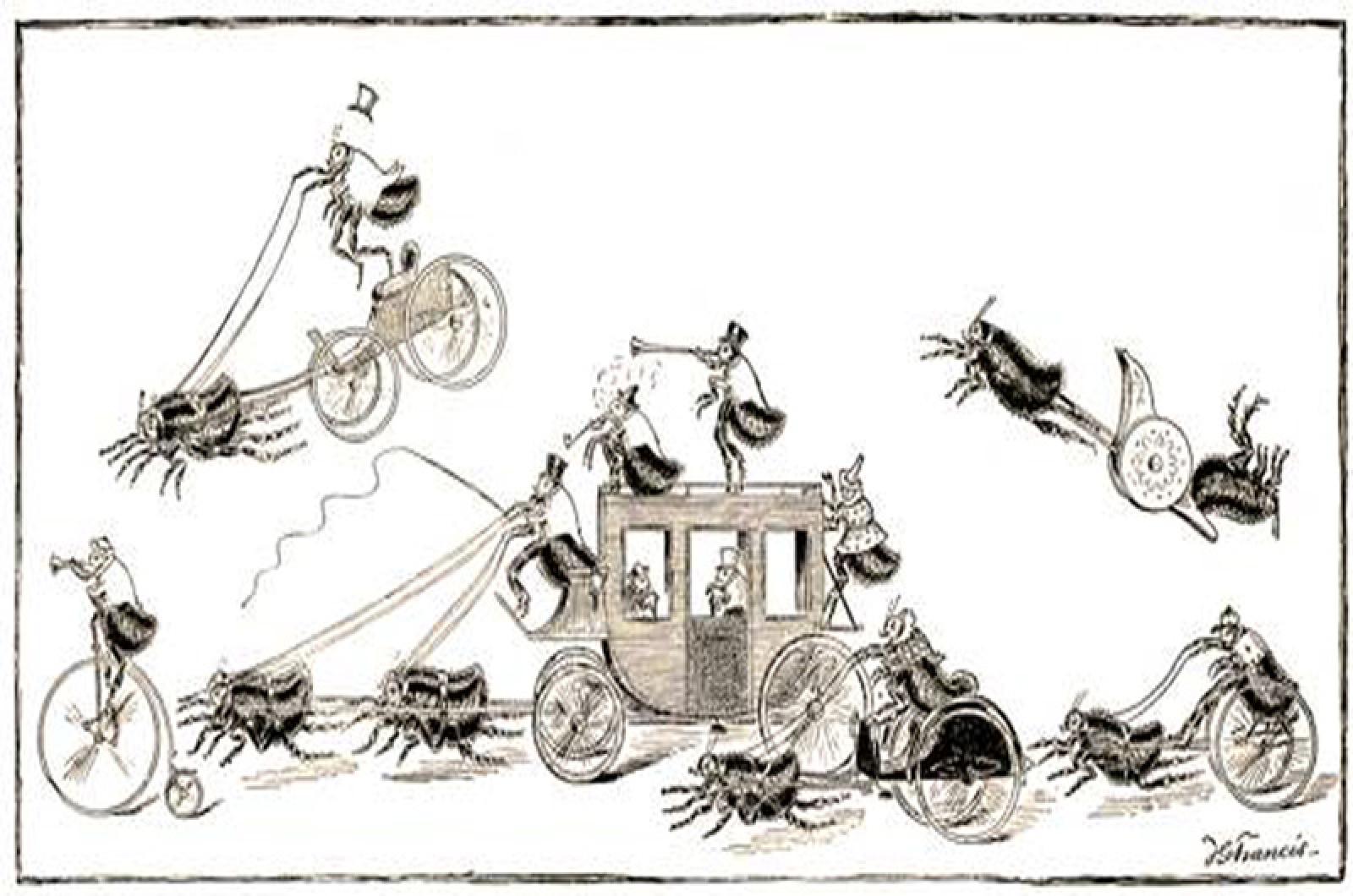

Next came a series of watchmakers who created miniature, flea-sized models of furniture, coaches, and chariots on which to install these insects. Their intent was to highlight their talent; however, fascination with the tiny reproductions and the animals which could pull, push, or alter them led to the flea circus craze.

Finding just the right flea for the job was both art and science. Only about one in 10 fleas are mobile and athletic enough to be successful in the circus world. These outliers can leap up to seven inches (150 times their height) upwards and a foot lengthwise.

Why fleas, though? The question is easily answered. They were quick to reproduce, cheap (free in most homes), had excellent shock value and ewww factor, and were plentiful at the time of this activity’s popularity. Feeding was also easy, with just a hop onto any willing volunteer for a quick blood meal.

Human fleas, Pulex irritans, were used, as they were readily available in most dwellings and beds. Fleas were collected and observed. The ones that could jump the furthest and were most active were chosen for the circus, since fleas could not be trained like a dog or other animal. The fittest fleas were collared with a thin gold wire to pull objects, or they were put atop a tightrope to walk it, or glued on their backs so that their legs would turn a ball or cog to make something move. Even juggling fleas were not uncommon. Another sick trick was to glue their legs to a tiny instrument so their movements to escape the glue would imitate strumming and they could make music. Since fleas only lived a few months, turnover was constant in the industry.

Credit for mastering these techniques and for the first circus goes to Italian Louis Bertolotto, who in the 1820s started his Extraordinary Exhibition of Industrial Fleas. His greatest accomplishment was his fleas’ enactment of Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo that involved 435 fleas performing at once.

In some cases, fleas weren’t even used; rather, trickster circus ringleaders substituted magnetic or electric fields to manipulate the miniatures and create a show.

The decline of the flea circus was not unexpected. The increase in home hygiene made possible by inexpensive vacuums and washing machines led to a reduction of human fleas in modern homes. Dog fleas and other varieties were deemed to be less effective and entertaining circus performers.

A few flea circuses (with and without fleas) remain and can be found in Munich, Germany, and even closer in Maine and Rhode Island, according to the international flea circus directory.

So while my sister wouldn’t hurt a flea, she was somehow quite intrigued by the creative ways people have manipulated them for entertainment purposes and those that paid to see them perform. I’d advise her that it’s usually best when one is cooped up in the house with the internet and its tales of tiny terrestrial torture to go with your instinct to escape from both — do what comes naturally: flee!

Suzan Bellincampi is executive director of the Felix Wildlife Sanctuary.

Comments

Comment policy »