Jessica Harris knows all of her Oak Bluffs neighbors, many of them well.

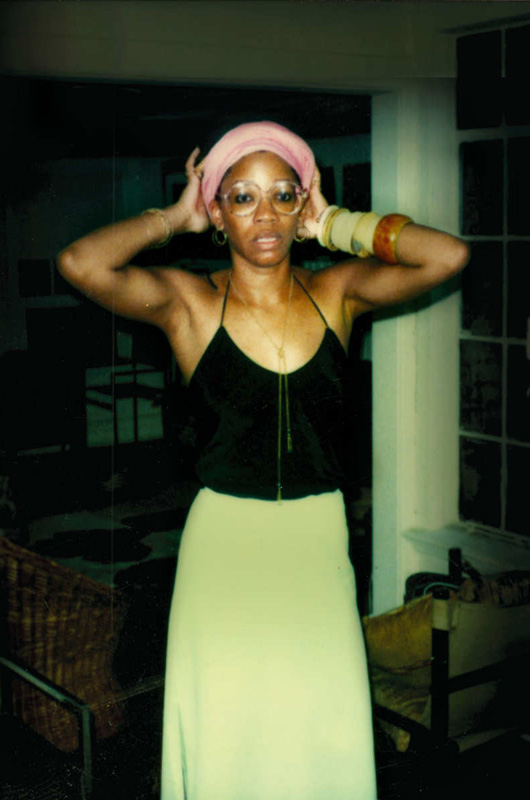

Sitting on her front porch on a recent afternoon, surrounded by pink wooden furniture, lamps, jars and a string of pink flamingo party lights, she pointed to the neighboring properties, each of which had a story.

“That used to be Clayton Hoyle’s baitshop,” she said, pointing to her right. Behind her was the former home of the Island’s first high school football coach, Dan McCarthy. Immediately to the right was an old garage that once belonged to the Walmsley’s, who owned a bakery.

A huge oak tree in the front garden shaded the yard with its low branches.

“That tree, my grandmother sat under it, and some of my father’s ashes and some of my mother’s ashes are in the knothole at the bottom,” she said, adding that the family cottage has long felt like home.

It is also where Ms. Harris, a well-known culinary historian and author, does most of her writing. Two summers ago, after the death of her friend and fellow writer Maya Angelou, she began writing her memoir, My Soul Looks Back, which revisits her relationship in the 1970s to Samuel Clemens Floyd 3rd, whose orbit included many of the leading black voices in New York city, including James Baldwin, Nina Simone, Ms. Angelou and others.

Next Thursday Ms. Harris will speak at the African American Cultural Festival, and in August she will discuss her new memoir at the Martha’s Vineyard Book Festival. “I am not central to the story, although I have lived it,” she writes in the memoir, which was released in May. “Rather, it is an extraordinary circle of friends who came together, lived outrageously, loved abundantly, laughed uproariously, and savored life while they created work that would come to define the era.”

At the center of it all was Mr. Baldwin, the “sun king,” whose life and career played out in New York city and France — the main backdrops of Ms. Harris’s early life as a writer and lover of cuisine. She recalls wild dinner parties and nights on the town in the days of Mikell’s jazz club and other West Side landmarks, rendezvous with the French chef Georges Garin in New York and Paris, and many other life-changing encounters.

“I’ve been known to say that I am the Zelig of the second half of the twentieth century because it has been my great good fortune to turn up in multiple special spots,” she writes.

Her early education at the United Nations International School in New York left her with a fluency in French language and culture that continued to blossom during her years with Mr. Floyd, the admired director of faculty and curriculum for a program at Queens College that aimed partly to matriculate more black and Hispanic students into the City University system. This fall will mark Ms. Harris’s 49th year teaching English at the college.

Her relationship with Mr. Floyd — and her love of travel and cuisine — brought her around the world, including to the South of France, where she recalls, among other things, visiting Mr. Baldwin at his home in St. Paul, where he disappeared for long stretches at the typewriter and emerged for evenings on the town.

“It was belonging but not belonging,” Ms. Harris said of her circle of friends at the time, most of whom were 15 or 20 years her senior. “I would always sort of define my position as being the tail end of the kite of the friendship that was theirs.”

But not every acquaintance depended on her relationship with Mr. Floyd. As a young journalist in New York, for example, she interviewed Toni Morrison after the release of her second book, Sula, in 1973. She recalled the way Ms. Morrison had worried over the opening lines, about a black neighborhood torn down to make way for a golf course.

“When you are 20 something and you are talking — you are listening, really, because it wasn’t that I was talking — you are listening to people who are paying attention like that, it can’t help but mark you,” Ms. Harris said.

She recalls intimate moments with Mr. Baldwin and Mr. Floyd, who shared a close friendship, including an all-night reading of Mr. Baldwin’s fresh manuscript for If Beale Street Could Talk, at his home in St. Paul.

“That was staggering,” she said. “I still can’t get over that.” She experienced it twice, the second time with Ms. Morrison, who offered expert feedback that was perhaps equally enlightening.

While Mr. Baldwin was the sun king during that time, Ms. Harris’s love of cuisine was also a center of gravity, around which orbited her love of travel, company, language and writing. “They all come together,” she said.

Each chapter in the book ends with a recipe that pays homage to people and places in her past: the Galician white bean soup that she discovered at El Faro restaurant on the outskirts of Greenwich Village, Mommy’s Sunday roast chicken, Maya Angelou’s new year’s kale, and other favorites.

“They are all sort of simple, hearty food,” she said, adding that with her job as a professor, she often doesn’t have time to cook highly elaborate meals. But it’s often the simple things that endure the longest.

In the case of Ms. Angelou, she said, inspiration came not just from her writings and intellect, but from her formidable cooking skills. She writes about a dinner at Ms. Angelou’s home in California: “Maya’s cooking was a virtuoso performance that was part monologue and part dance routine, totally engaging and absolutely fascinating.”

A version of the eight-boy curry that Ms. Angelou made that day (named for the servants who would have originally brought such a dish to the table) ends the chapter.

Eventually Ms. Harris and Mr. Floyd drifted apart. But many of the friendships forged during their relationship endured. Ms. Angelou, for instance, remained in touch until her death in 2014. And Ms. Harris’s adventures as a world traveler continue today. Last year she visited friends in Benin, in addition to her annual sojourns to Paris and the Oxford Literary Festival, where she rubs elbows with some of the world’s top chefs.

“I feel like I’m playing with the big kids,” she said.

Martha’s Vineyard took a back seat during her time with Mr. Floyd, although it has always been a home away from home. In the winter, she travels between Brooklyn and New Orleans, a city that she said has become the epicenter for many of her passions, including cuisine and African culture in the west.

Next on her list of projects is a book for the University of Mississippi focusing on antiquarian postcards that feature Africans in diaspora as they relate to food in the Americas. “That should come out next year,” she said. After that, she may turn her attention to Voodoo, another passion and one of the many African traditions that survive in New Orleans. “It may be the subject of my next book,” she said. “We’ll see.”

As she often does, Ms. Harris recently made an appearance at the fourth annual Cook the Vineyard event, along with many other Island gourmets, including Kathy Domitrovich of Lola’s restaurant in Oak Bluffs, who prepared Maya Angelou’s new year’s kale. By all accounts it was a hit.

“Kathy did a fabulous job with the kale,” she said.

Jessica Harris will speak about her memoir on Thursday, July 27 at 6:30 p.m. at the African American Cultural Festival, at Cottagers Corner, 57 Pequot Avenue in Oak Bluffs, and again at the Martha’s Vineyard Book festival the weekend of August 5 and 6.

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »