From Singing in the Morning, a collection of nature essays by Henry Beetle Hough.

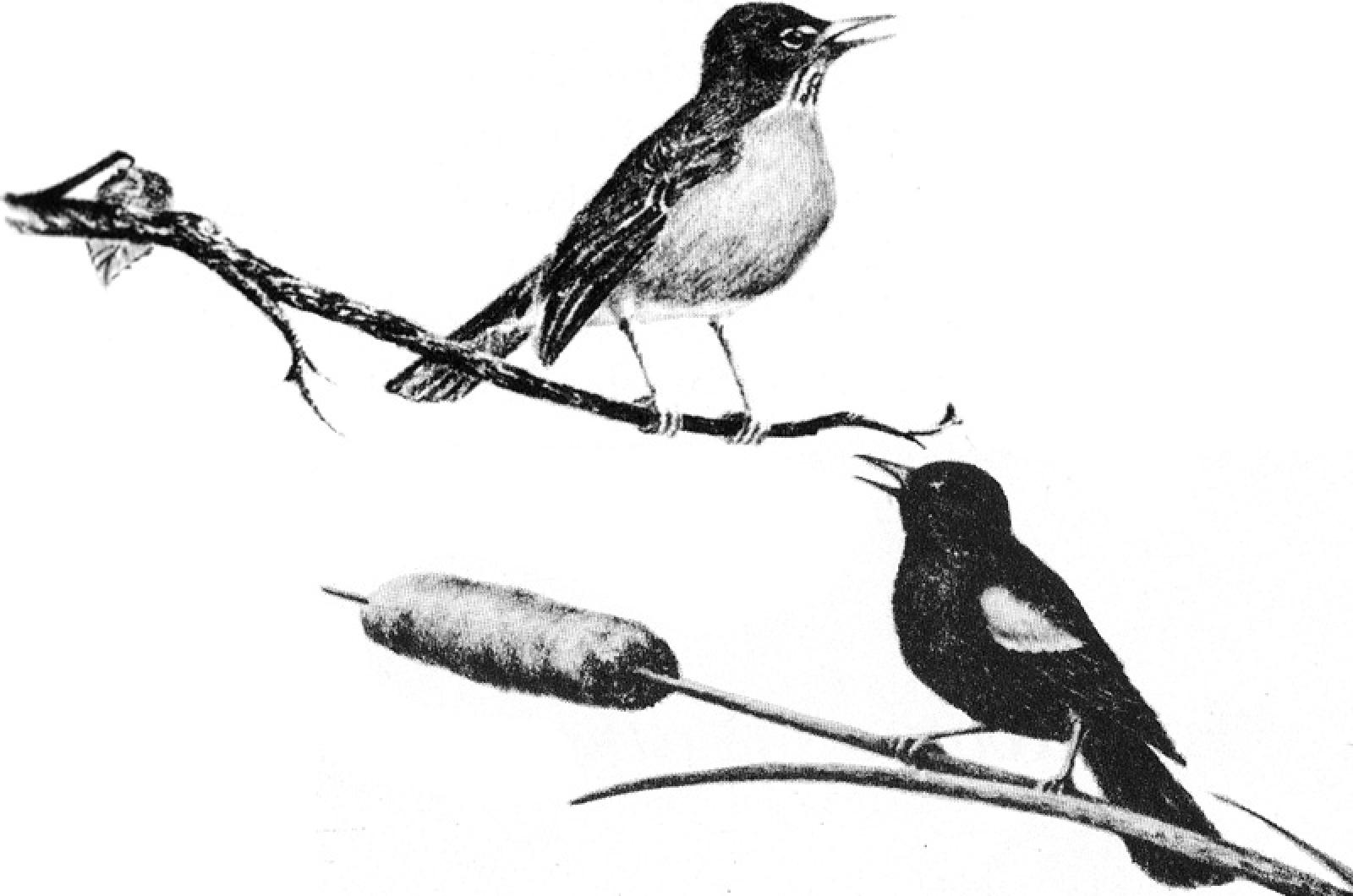

Two robins in a tree, then one flying low across the lawn with a characteristic call, as if to say that the robin may retreat but nevertheless retains possession, that he flies low on purpose because it is his lawn, and from now until sometime deep in summer he will not be far away. Then, besides the robins, a red-winged blackbird in the same wild cherry he so much liked all last summer. If this is not spring, what is it, no matter how much snow may still fly and how chill the winds may seem?

All nature is stirred, as if the robin or the redwing did it. One begins to look closely and sees not only the snowdrops in pure white flower against brown grass but budding tulips and daffodils and swelling buds on shrubs. Grass is green already in favored places.

What is it that makes the air smell and taste so different? We do not know, unless it is spring. Even when the winds are biting, the new scent is present, and one wonders if the robin and the redwing have noticed it and if that is why they are here. The longer hours of daylight seem less important than the smell and feeling of the air, for days lengthen with plodding slowness but the air brings its fresh tang suddenly, with excitement and quickening.

The business of peace is being carried on in this war-worried world by such welcome citizens as returning robins, and the more one notices them the better. Except for them there would be no spring, and the spring we still must have.

Comments

Comment policy »