It’s a misty May morning in Chilmark and Mitchell Posin doesn’t seem to have an agenda for the day. While other farmers race up and down South Road with their trucks overloaded with supplies, Mitchell strolls around the farm house kitchen. He wears a blue Allen Farm hat, stained yellow shirt, workpants, boots and a ripped black sweater. While sipping some water (he doesn’t drink coffee or even tea) he chats with his wife Clarissa and the farm’s weaver, Clare Ives. The conversation wanders from how the lambs are doing — none need to be bottle fed yet — to what needs to get done to prepare for an upcoming wedding, which will be held in one of the fields overlooking Lucy Vincent Beach.

The Allen Farm is a popular wedding destination and in high demand during wedding season.

“There is a lot of goose poop out there,” Mitchell says. “We have to get that up.”

There is a leaf vacuum to help with this task, but they’ll do most of the work on their hands and knees.

Clarissa and Mitchell’s 31-year-old son Nathaniel and his wife, Kaila, enter the kitchen. Mitchell consults the weather and reports that rain is coming. He and Nathaniel decide that the upcoming rain means today is a good day to seed one of the hay fields and some pastures. But first, they need to check on the lambs.

They head to what Mitchell calls “the bowels of the Allen farm,” where there is a giant meat freezer with dozens of coolers stacked up beside it, a large machine shop and a long barn that houses the farm’s fertilizer and custom grass and hay seed, which they sell, along with the farm’s prized wool and meat. The barn is also home to Mitchell’s cherished 1,500-gallon compost tea brewing machine. He also has two smaller 250-gallon machines.

Mitchell greets the farm’s mechanic, Steve Broderick, who reports that all in all, things are in pretty good working shape. Kaila appears and the four run through the day’s agenda, refining it again.

Back outside, while ambling down the road that runs between several of the farm’s pastures, Mitchell is electrified by the sight of worm tracks in the dirt.

“This is fantastic,” he says “I want to have one million worms per acre or 25 worms per square foot. Twenty-five worms per square foot means they are making 50,000 pounds of earth worm castings. We’re not there yet, but I want our land to jiggle with worms. Every square inch filled with worms.”

Mitchell pauses to explain his excitement. “When they grab a leaf or a blade of grass, they make the NPK — the nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium — four to five times more potent. The mucus, slime on their body draws the NPK down into the soil. Years ago, when I first started clearing this land, we had about one inch of topsoil. Now we have eight to 10 inches in the areas that we’ve been farming for 40 years. It is amazing.”

He stops for a moment, gauging his student like a good professor.

“Let me back up a bit and start at the beginning. You know the periodic table of elements you were supposed to learn, that has 90 elements? Well, we are trying to make sure those 90 elements exist in the ground. Most fertilizers have three. You know, the 10, 10, 10 with nitrogen, phosphate and potassium. Well, I like to use Azomite [if he is going to use a fertilizer], which is from volcanos and has 70 of the 90. And then there is kelp, which has basically all of the 90. And this is why my compost tea machine is so important. It helps us extract and inoculate the soil with the necessary bacteria, fungi, nematodes and protozoas — the predators and prey of life — into the soil. Everything is alive. In two good handfuls of organic soil, there could be more critters, more microorganisms, than all the people on earth. More than eight billion.”

And this is when one realizes that while Mitchell’s daily agenda may seem loose, his program and vision for how to live is anything but haphazard. He wants to be the best steward he can possibly be of the Allen Farm, which has been in his wife’s family since 1762.

In 1975, Mitchell was living and working as a woodworker in Brooklyn, N.Y. when he had the choice of helping to refurbish the captain’s quarters for a marine research vessel owned by Columbia University, which at the time was headed out to an oil spill. Or he could come to Martha’s Vineyard to help a business partner build his parents a home. When he heard that the boat might be sailing in 100-foot seas, Mitchell opted for the Martha’s Vineyard.

“It was a great decision,” he says. “Not just because I met Clarissa, but also because I later learned the boat ended up getting frozen in the ice.”

Mitchell says he was smitten by Clarissa right away. “She took more convincing. But I had one thing going for me. Her mom liked me.”

Since then, Mitchell and Clarissa have been on a 41-year effort to revive and restore the farm. He gestures to the wide green fields around him and reports that he has reclaimed 6,000 feet of stone wall around the farm, clearing most of the 100-acres. He points to a pasture up a hill that abuts the Eddy family’s property.

“You see that. That is relatively new. We’re still just peckin’ away here. It is so great now that Nathaniel has taken over.”

Nathaniel nods. “He hasn’t killed me yet.”

“Nathaniel has helped me be a better father,” Mitch says. “Once when he was a little guy and I was reprimanding him about something. I don’t remember what it was, he said, ‘Dad, I don’t mind what you are saying, but I do mind how you are saying it.’”

“I don’t remember that,” Nathaniel counters.

Father and son crest a hill that overlooks the farm and watch Kaila who is in a large pasture working with the ewes and lambs. Kaila has a can of stock spray tucked in one armpit and is wielding a lamb “crook” (a staff with a hook), trying to catch a baby lamb. The scene looks like it could have stepped out of a painting from another century.

Mitchell points out that most of the ewes have had twins. “Just before we introduce the ram, we put them on our richest pasture and feed them organic grain. This extra nutrition makes their bodies inclined to drop more eggs.”

He adds: “We also have lambs later in the season so that the mothers have more food before they give birth and have healthier lambs.”

Kaila grabs a small black lamb. “I think I’m going to give this one some formula.”

Nathaniel and Mitchell inspect the lamb and agree that it looks a little dehydrated. Then they head off to another part of the farm to work on a grass seeding project where they carefully create a sort of seed lasagna layering their North Country Organics Allen Farm hay seed mix with mycorrhizal fungi, rhizobia and cover. Mitchell explains that the mycorrhizal fungi are for the hay’s roots, and the rhizobia bacteria fix the nitrogen for the clover’s roots.

Once the seed spreader is loaded, they drive over to the hay field to take a look. Nathaniel starts running the tractor and Mitchell tells him to up the RPMs of the spreader a bit.

“Even if we don’t get the whole field, just getting the edges will be an enormous help,” he says.

Once Nathaniel is set, Mitchell checks the cow manure that he is prepping for his compost tea brew. In the fall, he mixes cow manure from lactating cows with other biodynamic materials and puts them in nine, two-foot wide cement pipes that function as pots set into the ground. These sit for six or seven months before he uses the manure to make his compost tea, which he then sprays on all his fields. This is the key to his nutrient rich fields and dense topsoil.

“We use a hydraulic sprayer that doesn’t heat up the tea,” he says. “A piston sprayer would create too much heat and disturb the microorganisms. By the way, a compost heap should never be more than six feet wide or four feet high. It needs air.”

Happy with the manure’s progress, he walks back to his house to have lunch and points out a hoop house on a hill on the way. “That’s for our meat birds. We just raise them for ourselves. We do about 100 at a time. We grow them big, five to six pounds. They’d be too expensive for us to sell. So, I basically do all this to feed my family. And I want them to have the best food possible.”

Mitchell strolls into the kitchen and serves himself some of his goose stew.

“Clarissa used to come to bed with piles of cookbooks and I didn’t understand it. Now that I’ve started cooking, I do it too.”

Nathaniel soon joins him and after lunch they take seats by the 12-foot by 9-foot fireplace. According to legend, during the Revolutionary War the family used the fireplace and its chimney as a place to hide their animals from Grey’s raids.

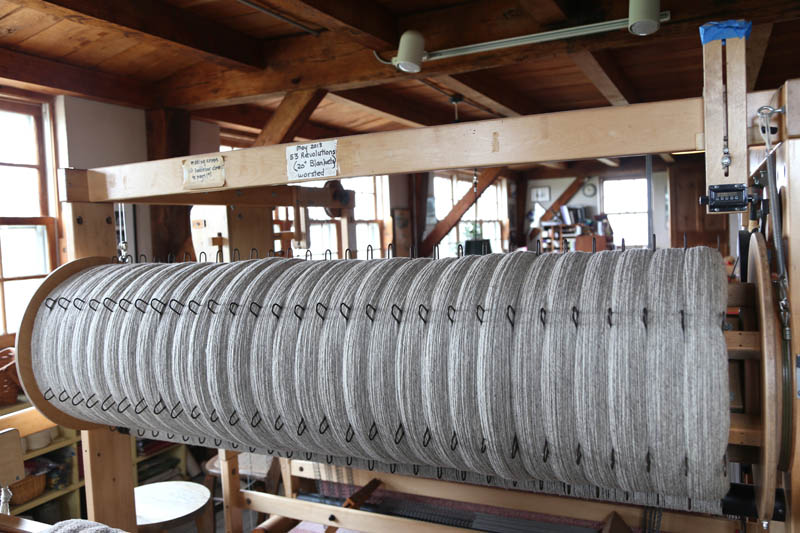

After lunch Nathaniel and Mitchell head out to the storage barn, which also houses the farm’s office, large blanket weaving loom and Nathaniel’s family. They check in with the farm’s accountant, Michelle Cacchiotti.

“Are we solvent?” Mitchell asks.

“For the moment,” Michelle responds.

Mitchell laughs and heads downstairs to put more seed together for the fields. When the spreader is loaded once again, Nathaniel drives off to some other chores. Mitchell watches him go.

“It’s so nice not to be the guy in charge anymore,” he says. “Nathaniel’s got it. I’m so lucky we had him and that he wanted to do this. And Kaila, she’s just the best woman. She’s doing the lambing, is in the garden all the time. She is a great mom. You know, Tavira was the first baby born on the farm, really on the farm, since 1896.”

Mitchell points to a spot where he’d like to build a house for Kaila and Nathaniel.

“What we have to do here is endless,” he says. “But, you see, little by little we are making this place better.”

Mitchell Posin: From the Ground Up

Age: 67.

Profession: farmer, member of the Chilmark planning board and a Chilmark road agent.

Born: Brooklyn, N.Y.

Raised: Brooklyn. “I went to the same grammar school and high school as Bernie [Sanders].”

Education: “I couldn’t read when I left high school.”

Moved to Martha’s Vineyard: April, 1975.

Family: Clarissa Allen, wife; Nathaniel Allen-Posin, son; Kaila Allen-Posin, daughter in law; Tavira Mirai Allen-Posin, granddaughter.

Animals: 1 dog named Boli (an Icelandic sheep dog), 2 horses, 2 burrows, 70 or so chickens, 60 ewes, 10 yearlings and 50 lambs (so far).

Comments (7)

Comments

Comment policy »