From the Jan. 23, 1959 edition of the Vineyard Gazette: Time was when traffic in Vineyard Haven was a delight, not a headache. The old livery stable is still there but it is a taxi-stand now. No longer do parties of riders with tasseled fly-nets over the ears of their mounts go gaily forth for a gallop.

Gone are Al Luce, his team and the low-bodied dray, or “jigger.” Another familiar was Dolph Manning’s big black, a Satanic creature whose fractious behavior finally brought death to Dolph under the wheels of his cart.

For style Mrs. Skeel from Seven Gates set the pace, in a rubber-tired surrey, and a team of perfectly matched chestnuts, handled by a coachman who kept the turn-out glistening.

There would be a brisk tattoo of hoofs as a handsome horse at a smart trot breezed along between the shafts of Carey Luce’s run-about.

Occasionally everything came to a standstill as Harry Horton moved a house (or part of a house) through the town. People from “the Neck” (Hatch Road today) never complicated traffic. They rowed to town, beached the skiff near the dock, and walked up to get the mail or pick up the paper at Charlie Vincent’s.

For variety there was Craig Kingsbury’s ox-team, seldom seen on Main street today. Or perhaps it was Cap’n Zeb Tilton, big enough to weather any traffic, on his way to pick up a sea-going anchor, hoist it on his shoulder and carry it down the dock.

The era of color and charm in the town’s traffic reached its climax when in the gasoline rationed war days Katharine Cornell replaced petrol with oats, driving in from Chip Chop behind a patient white horse. A moment to remember was when the impeccable Clifton Webb, gloved hands on the reins, maneuvered the Cornell steed into a parking place in front of the bank.

Vineyard Haven street scenes were delightful in those days. It’s a different picture now, and it “ain’t quaint.” Time to do something about it and make some sense.

The state of the union has been dealt with in a message from the President, as required by tradition and the laws of the nation, but not for a good while has there been a message about the state of the Island, a matter of a different kind, important maybe not to millions but certainly to thousands. The state of the Island — there’s a timely, hearty subject.

Things are coolish, of course, and the landscape has fallen in with the style of an old fashioned hard winter. The lichens still grow in table-mat design on gray boulders, and the boulders lie as in ages past on the hills and in the woods. On a clear, calm morning Vineyard Sound is patterned in streaks of different shades of blue, and when the rain and fog settles in an occasional foghorn can be heard, muffled and far off, but nothing like the number that Vineyarders heard a generation or more ago.

There’s frost in the ground, but on the surface it’s a case of freeze and thaw, and dirt roads are rutting. Wagons can’t sink up to the hubs, however, for there are no wagons to speak of. Wood smoke rises from certain houses where old customs persist, lights shine at night but not with the glimmer of oil lamps used to bring about. There’s ice in the swamp holes, some shrubs and trees have buds, and myrtle stays green in old dooryards.

The state of the Island differs not much in fundamentals from that of Thomas Mayhew’s day. Long may the fundamentals endure!

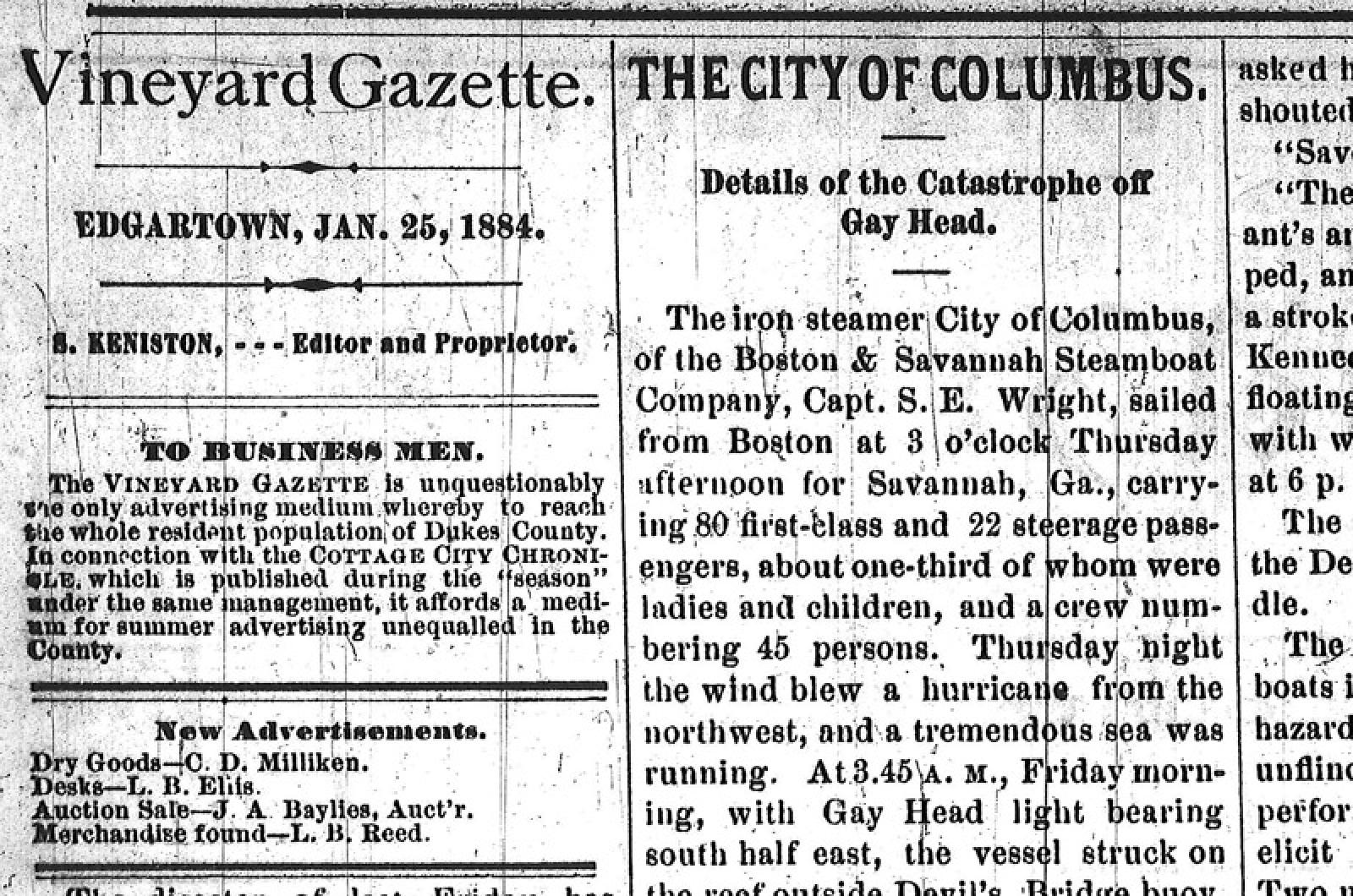

Seventy-five years ago on Jan. 18 the steamer City of Columbus, bound from Boston to Savannah, steamed into a sunken rock of Devil’s Bridge, off Gay Head, at 3:45 in the bitterly cold morning, and in the wreck and ordeal that followed, 121 persons lost their lives. Seventy-five years have passed, and the wreck of the City of Columbus stands in marine history and in Island history in a pattern of classic tragedy.

Two years ago last summer, diving off Gay Head, Wallace E. Tobin and John Farrar, using the modern technique known as skin-diving, believed that they found the rock on which the City of Columbus drove that terrible morning. If, as tradition has it, a deviation of a few yards on either side would have seen the vessel safely over Devil’s Bridge, the feeling of tragedy is heightened.

The weather that morning was clear, lighted by bright moonlight. The cliffs of Gay Head were so close that under different circumstances they might have promised a safe refuge. Only one factor seemed to have doomed the City of Columbus and her 121 victims — that inexplicable, split-second happening that sometimes becomes irrevocable and catastrophic beyond cure. The second mate, who was in charge of the pilot house, did not survive the wreck and could never give his account of the disaster that should not have happened, but did.

For many years afterward the bell of the City of Columbus, installed in the Lambert’s Cove schoolhouse, called Island children to their lessons, and many a Vineyard household possessed some relic or other of the wreck — a mattress, a carpet-seated chair, a strip of paneling.

Compiled by Hilary Wall

library@mvgazette.com

Comments

Comment policy »