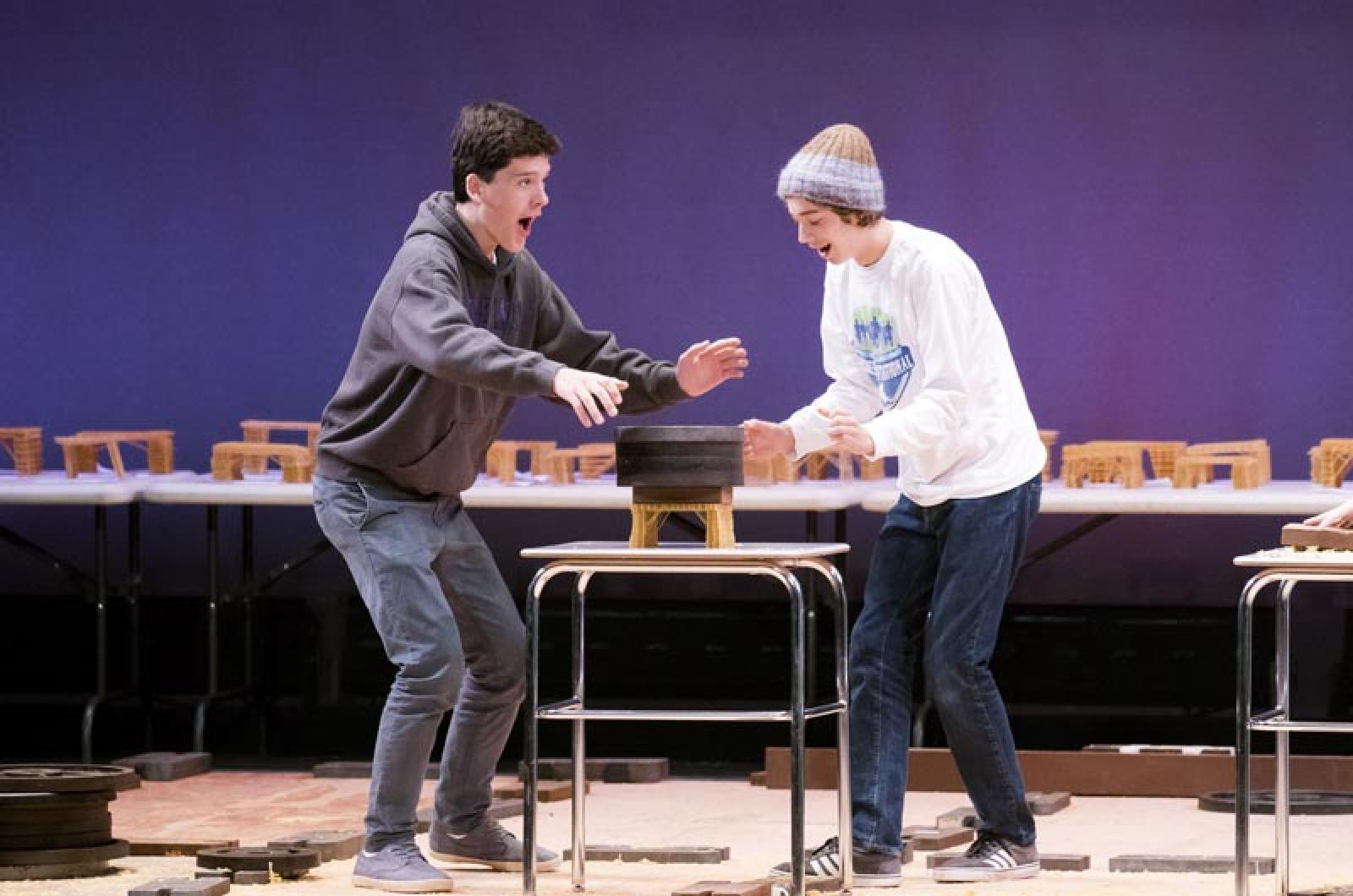

Tension was high at Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School on Monday as freshman Graham Lewis placed another 45-pound weight on top of a small bridge he had made of linguini.

Graham had made it to the final round in the 18th Linguini Bridge Contest, and was already far ahead of the competition. Finally, the bridge cracked and collapsed, sending 27 free-weights - 1,215 pounds - cascading to the back of the stage.

Well over 100 hundred students gathered Monday morning in the school’s performing arts center, where 1980s pop music blared and stacks of circular free-weights lay in stacks on the stage, along with a layer of broken linguini and bridge parts.

Using nothing but Prince linguini and Elmer’s glue, students built about 90 bridges this year, with names like King Cobra, Augustus and the Get Over It Bridge. Graham’s winning bridge, which supported 1,170 pounds, was simply named Bridget.

According to the instructions, students could work alone or in teams. “Each team may get help from teachers, parents, carpenters, architects, engineers, Italian chefs, priests, rabbis, etc.”

Contest founder and freshman math teacher Ken DeBettencourt said Stop and Shop has learned to stock up on Prince linguini in the days prior to the contest.

In recent years, construction methods have improved, he said, at least partly because students can research online videos from past contests. Gordon Moore, whose bridge three years ago held 2,170 pounds, still holds the school record. Last year’s winning bridge supported 1,500 pounds.

“We all watched the videos from Gordon’s,” said Nicole Arruda, whose team used a popular checkerboard design. She also emphasized the importance of strong vertical supports.

Julian Herman said his strategy was to use “layers upon layers for the legs and the base,” with some strands doubled up for support.

One team this year constructed its bridge from side to side, rather than from bottom to top, which Mr. DeBettencourt said was a first. That team made it to round three, when their bridge collapsed under 540 pounds.

No bridge could weigh more than one pound, and each one had to be at least three inches high, five inches long and four inches wide. While there was no special prize for the winner, students were graded based on the beauty and strength of their bridges.

Graham’s design was deceptively simple, with thick vertical supports and a simple top “We put pasta straight across each row that was standing up, so that when the weight was put on it was distributed throughout the whole thing,” he said. “We just did the middle as thick as we could make it, without it being over a pound.”

In general, it’s the vertical supports that make or break a bridge, said math teacher Melissa Braillard, who co-hosted the event along with Mr. DeBettencourt.

Mr. DeBettencourt said the contests teach students about vertical force, weight distribution and balance, while also offering experience in teamwork. It also creates a bonding experience for the entire grade, he said, and memories that may last a lifetime.

The contests have also become better organized over the years. “I used to do this by myself, and this was the best year I’ve ever had,” Mr. DeBettencourt said. “It ran beautifully today.”

Comments

Comment policy »