At high tide on a sunny day in the year 2100, a visit to Five Corners in Vineyard Haven could mean a swim with the fishes. A man strolling along Dock street in Edgartown might find himself chest-deep in water, and a large portion of the Inkwell Beach in Oak Bluffs could be swallowed by the sea.

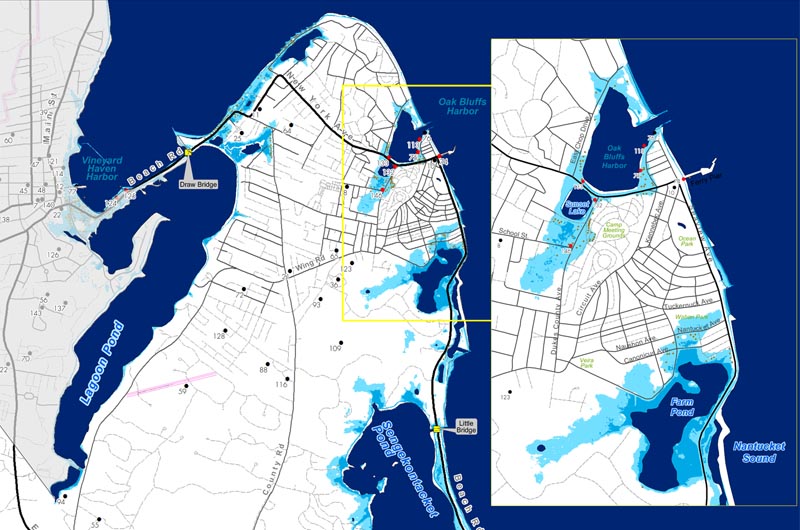

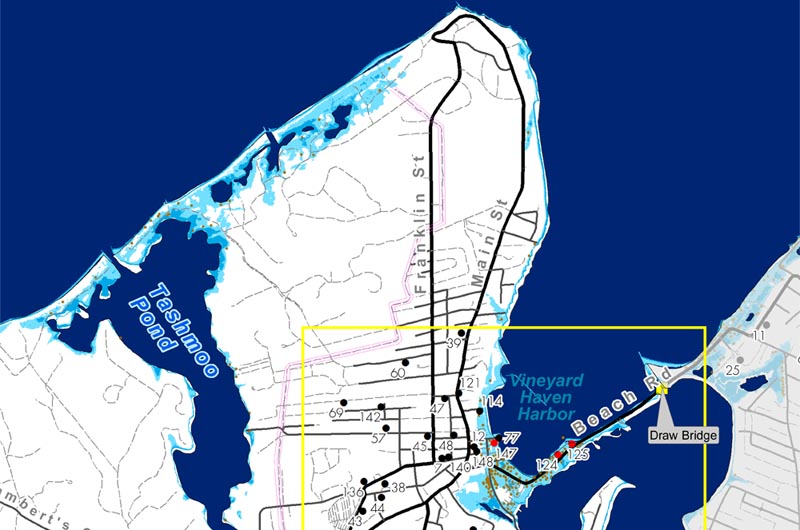

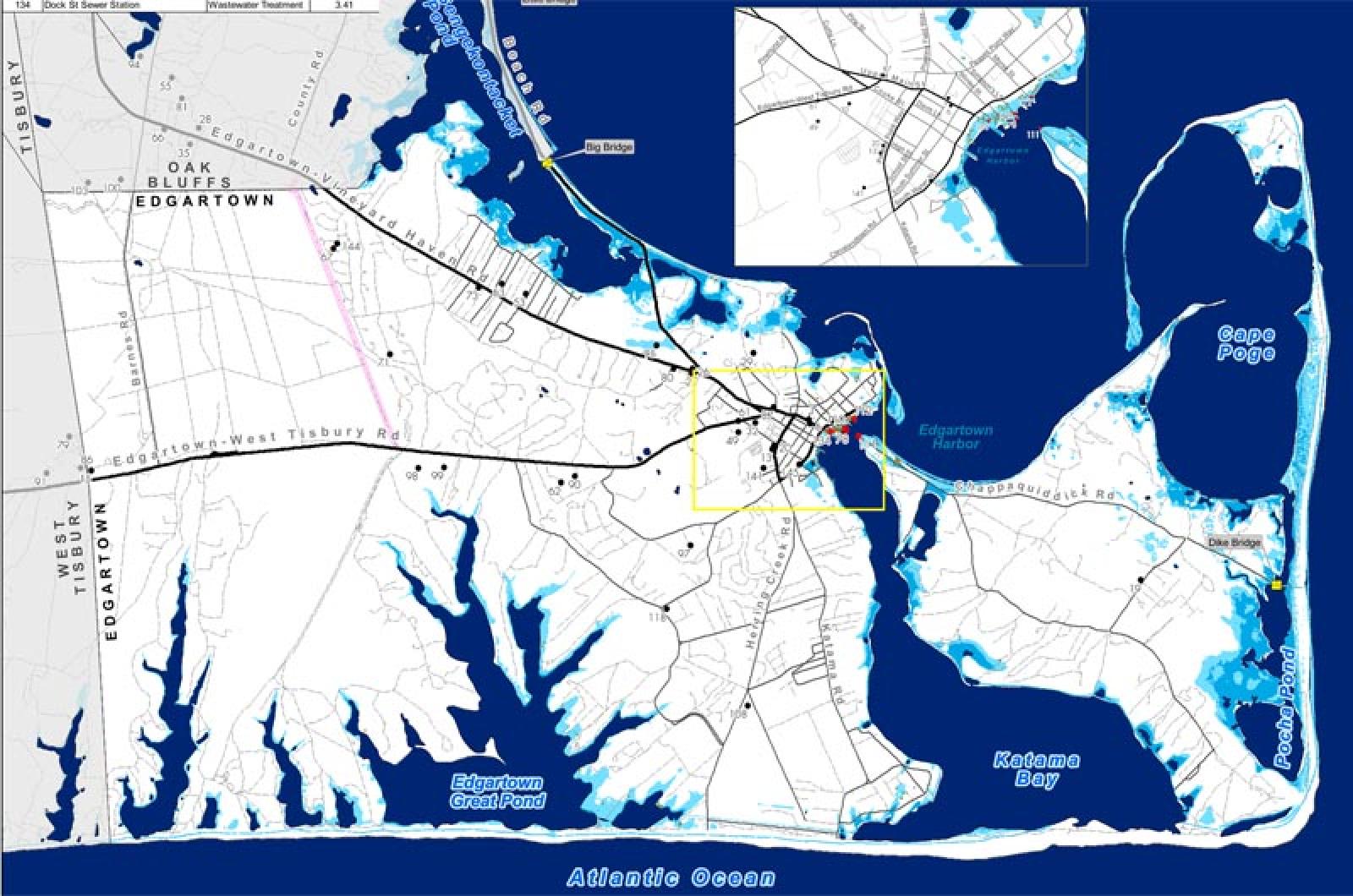

These likely victims of sea level rise are highlighted on a new map created by the Martha’s Vineyard Commission that shows possible changes in the Vineyard seascape for future generations.

According to the projection used for this set of maps, the level of the ocean around the Island could rise one and a half feet by 2050 and five feet by 2100, surpassing estimates for some other parts of the world.

For down-Island towns, rising seas threaten homes, businesses and critical public infrastructure over the long term.

While sea level rise worldwide has averaged two millimeters per year between 1971 and 2010, according to the International Panel on Climate Change, sea level rise at Nantucket averaged 3.94 millimeters per year in a similar period of time, according to a study performed by NOAA.

Maps showing potential sea level rise are part of a broader project at the Martha’s Vineyard Commission to plan for natural disasters. The so-called Hazard Mitigation Plan, the second such plan the commission has produced, came out in draft form in March. Cartographer Christine Seidel and coastal planner Jo-Ann Taylor collaborated on the plan.

The Martha’s Vineyard Commission combined local subsidence levels with some of the most conservative estimates for sea level rise to present a likely scenario useful to planners.

Their computations show that down-Island towns are at a clear disadvantage when it comes to sea level rise. Though losses are somewhat minimal for the first part of the century, by the year 2100, an estimated $30.9 to $64.5 million of developed land in each of the down-Island towns will be threatened by sea level rise.

Tisbury stands to lose as much as $48.8 million in infrastructure by the end of the century, including 177 buildings and three critical facilities. In Oak Bluffs an estimated $30.9 million worth of developed land and 108 buildings are at risk. In Edgartown $64.5 million worth of property and 75 buildings are estimated to be at risk.

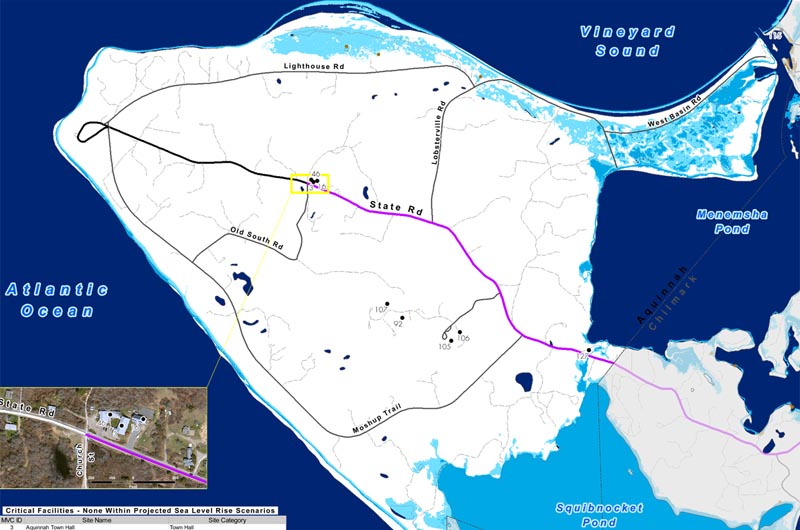

The up-Island towns are projected to fare better. Only three buildings in Aquinnah, for example, are threatened by significant sea level rise by the year 2100. For Chilmark, the maps show that nine buildings are threatened by sea level rise, which together have an assessed value of about $3 million.

The maps are more precise than their predecessors, but they remain educated guesses about the potential impact of sea level rise on the Vineyard, planners caution, and the models that created them are far from perfect.

The maps model the sea as a bathtub, in which the water has a uniform height throughout.

In reality, sea level rise is complicated by other factors, including subsidence, or sinking, and constant changes in the geometry of the shoreline due to erosion.

“Everyone is facing the same problem,” said Mark London, executive director of the commission. “The model is not really there yet.” More accurate modeling might be available to the commission within a few years, he said.

While most available maps, including the current elevation modeling from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, involve historic data, sea level rise projections approximate the future.

“They are all backward-looking, they are all looking for trends,” Mr. London said of the FEMA and other maps. “These are trying to project more into the future.”

For the plan, the commission has also mapped the Vineyard with respect to hurricanes, northeasters and wildfires.

Wildfires, though infrequent, have wreaked havoc on large parcels of the Island in the past. The Island’s sandy soils, which drain quickly, increase the risk of a wildfire, as do the large number of decaying pines in the state forest, according to the hazard mitigation plan.

Though West Tisbury can breathe easy with respect to sea level rise, it might do well to turn its attention to wildfire hazards.

The town has 12 critical facilities located in vulnerable wildfire territory, according to the commission’s new maps.

The maps will help the commission in reviewing coastal developments, Mr. London said. They are also a planning tool for town planners and emergency management personnel.

Eventually, the maps could lead to changes in zoning for areas that are at greatest risk, Mr. London said. “If an emergency arises, and someone needs to be rescued, it’s going to be the volunteer fire department or police department who has to go out there and risk their lives,” he said.

In the future, people may begin moving out of risky areas or including features in the construction of their homes that protect them from natural hazards, he said.

A third audience for the maps is the Vineyard homeowner, who can look to them to find out if their neighborhood is projected to be a high-risk area. Individual homes are not easily identifiable on the maps, though some shops and houses appear denoted by a brown dot, indicating they might be affected by the disaster depicted on that map. In some cases, residents of vulnerable neighborhoods can take practical steps to protect their homes from disaster.

For example, homes threatened by wildfire might consider replacing traditional cedar shingling with an asphalt roof, and clearing underbrush away from the house, Ms. Seidel said.

Preparation for hurricanes and northeasters can involve similar practical measures, Mr. London said.

“Do everything you have to do to batten down your house for a storm,” he said.

The planning of new facilities can now take these maps into consideration, and make efforts to minimize the effects of a given hazard on the integrity of the structure. For example, when the new hospital was built a few years ago, it was built from brick, which has high storm resistance, Mr. London said.

Though much of the world is vulnerable to the effects of climate change, much of the Island’s economy is dependent on the port towns.

“We are particularly at risk because so much of our infrastructure is near the water, especially the downtown of the three main towns,” Mr. London said.

Fortunately, the commission had the foresight to set up a coastal district of critical planning concern to limit development right on the edge, he said. The coastal district was one of the early DCPCs created by the commission in the 1970s. “They weren’t doing it with hazard mitigation or climate change in mind, they were doing it for natural ecology, or to preserve the views, but in retrospect other places in the U.S. would have been better off had they done what the Vineyard did,” Mr. London said.

These days, people have become more aware of the risks involved in buying property vulnerable to the ocean’s fury, he said. Several homes on both Islands have had to be moved or demolished to avoid being sucked into the ocean. “I think it’s going from a very long-term, theoretical threat that can be ignored to something very real and short term,” the MVC executive director said.

The maps attempt to make natural threats relevant for Islanders, who may otherwise think of them in abstract terms.

“It’s our job to step back,” Mr. London said. “People are involved in their daily lives, and what they are going to have for supper, and which beach they are going to go to, or which job they are going to go to if they are working three jobs. It’s our job to step back a bit and to look at the bigger picture, whether it’s geographically or in terms of time. What might things be like 30 years from now, and is that really where we want to go?”

The draft Hazard Mitigation Plan and corresponding maps are available through the commission website, by searching “Hazard Mitigation Plan” in the search key at mvcommission.org.

Comments (15)

Comments

Comment policy »