There were plenty of problems on the table and few easy solutions at hand as an influential panel convened Thursday evening to discuss the issue that has gone unnoticed in this issue-laden presidential election year: unemployment and high poverty rates in the African American community.

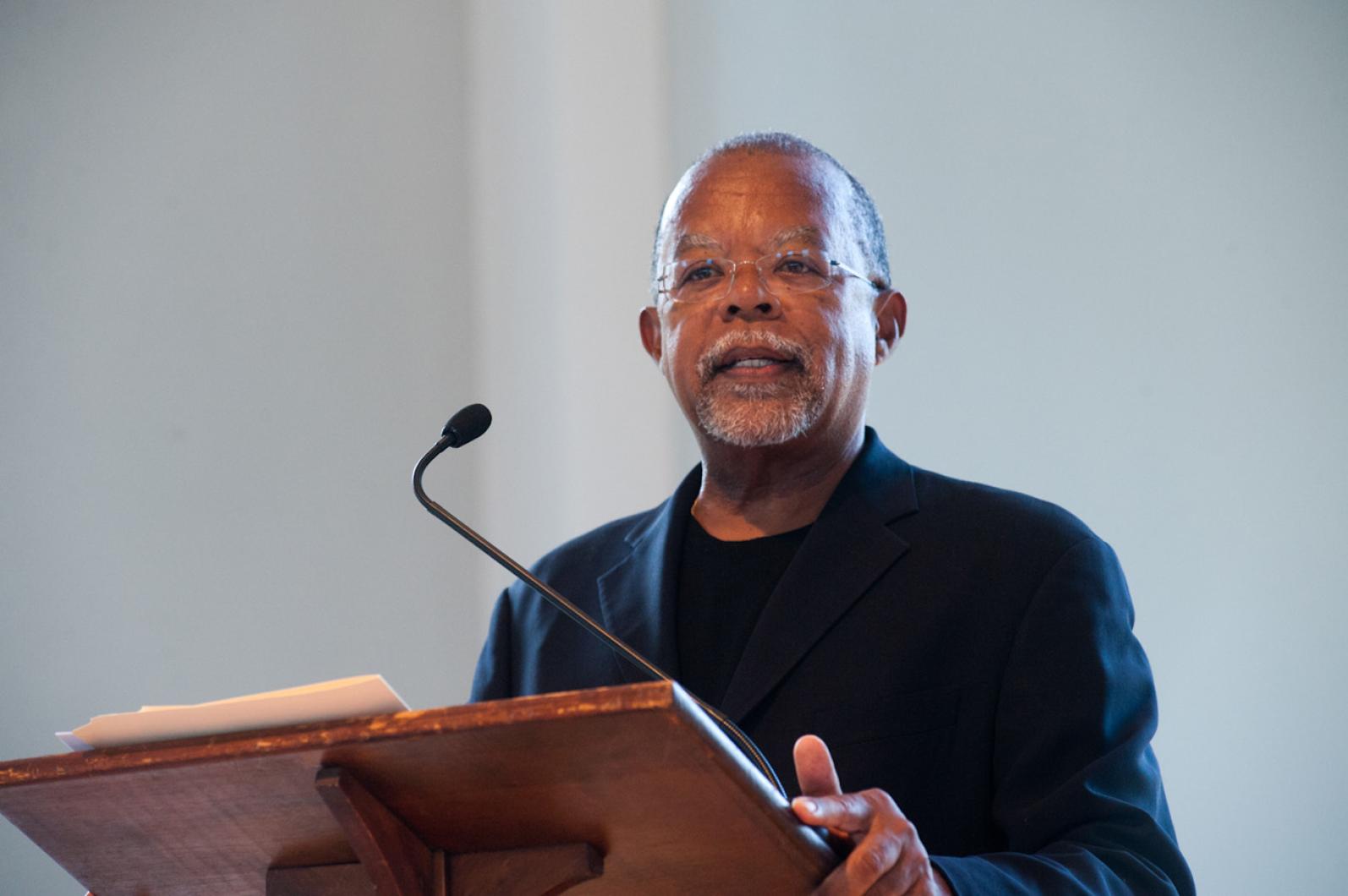

When Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968, few “would have anticipated that in the year 2012, we would have the largest black middle class in American history,” said forum host Dr. Henry Louis (Skip) Gates Jr.

At the same time, he said the percentage of African American children living at or below the poverty line is roughly the same: in 1969, 39.6 per cent of all African American children lived in poverty, he said, compared to 38.2 per cent in 2011.

“No model predicted this,” Mr. Gates said. “We all thought a rising tide would lift all boats.”

Over the course of the Thursday evening discussion at the Old Whaling Church, titled When Work Disappears: Equality and Opportunity in the African American Community, five panelists pointed to disproportionately high numbers of incarcerated African Americans, the war on drugs — and chiefly — failures in the country’s education system as reasons for higher rates of unemployment and poverty among African Americans.

The annual forum, sponsored by the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research at Harvard University, was renamed this year in honor of Glenn Hutchins, the longtime sponsor of the event.

“What many of us thought was only about race turns out to be vastly more complicated,” Mr. Gates, director of the Du Bois Institute, said in his introduction.

Poverty alone did not create the situation, Mr. Gates said. “Rather, it’s the loss of work, the loss of hope embodied in work, and its companion loss of motivation and self-sufficiency in our urban centers that have been so terribly destructive.

“Race can never be taken out of the question,” he added. “The questions we have to ask is how we got into this terrible place. Are the causes structural, are they cultural, behavioral, or some combination of both?”

And then there was the most important question: “Is the class divide permanent?”

Forum moderator Charlayne Hunter-Gault guided the wide-ranging discussion with a firm hand, exhorting panelists to be pithy and brief in their remarks.

“Here’s the stark statistic,” said panelist Lawrence H. Summers, former secretary of the treasury and former Harvard University president. “One in three African American men of working age is not working at this moment.”

He said that when the economy fully recovers from the recession, it will still be true that one in four African American men will not be working.

The data “is telling us that we have a problem in failing our children in preparing them for the demands that are expected of a modern society,” he said. “We are not making the kinds of investments in preparing our children for the modern world that we need.”

The theme was echoed by other panelists.

“We are absolutely wasting away our most precious resource, and that is our children in [kindergarten] through [12th grade],” said Roland G. Fryer Jr., an economics professor at Harvard.

He provided some staggering statistics: among eighth graders in Detroit, he said, three per cent can read at grade level. “There is not a city in America in which more than 25 per cent of black or Hispanic children can read or do math at grade level. To me, that’s an absolute crisis . . . I don’t even want to live in a country where we allow that to be true too much longer.”

But Mr. Fryer said that among those who score the same on eighth grade tests, regardless of race, future rates of unemployment, income, and incarceration become much more similar.

“What we have to figure out is how to take our most vulnerable populations . . . and make sure that no matter what circumstances they’re coming from, we can educate them,” he said.

Civil rights lawyer Constance L. Rice, the co-founder of policy action organization The Advancement Project, said work has disappeared for her clients in Los Angeles housing projects. She said the business of the community is gangs, and 70 per cent of the local economy in the housing projects is underground, with 60 per cent criminal: drugs, human trafficking and grand theft auto.

“This recession’s about the middle class,” she said. “My clients have had 67 per cent unemployment for four generations. They would love 14 per cent.”

“What I’m afraid of is that for the underclass, the disappearance of work may be bordering on permanent,” she concluded.

“This trend of work disappearing is very gendered; this is not a problem you see among either white or African American women,” said Heather Boushey, senior economist for the Center of American Progress.

“Whatever’s going on is affecting men and women very differently,” she said, noting that there are not similar declines in male employment in other developed countries.

She also pointed to an educational statistic: rich kids who are low scorers on standardized tests have the same chance of completing college as poor kids with high scores, she said.

“I think that this is happening and it’s going to continue happening, because there’s no economic incentive to stop it from happening,” said journalist and author David Simon, the creator of the television show The Wire. “We have mistaken market forces and the free market and unencumbered capitalism for social policy.” He continued:

“Joblessness is here to stay unless we rebel, because there is no economic incentive to get rid of it. It’s right to value every eighth grader, but there’s no money in it and no profit in it.”

He also pointed to the war on drugs and the high rates of nonviolent offenders in federal prisons, which he said disproportionately affects the poor and makes it hard for those with felony records to get a job.

“This is the darkest chapter in America yet,” he said. “The first act of rebellion which is possible for all of us . . . they ask me to be one of the 12 people to put a 13th in prison for a nonviolent drug offense, I’m going to nullify that jury as a moral act.” Applause filled the room.

But the discussion returned repeatedly to education. Mr. Fryer said two years ago he worked to transform the 27 lowest performing schools in Houston and Denver by giving struggling students extra time to catch up, getting rid of the principals and half the teachers, and lengthening the school day and school year.

“They had high expectations and they took no excuses for failure,” he said. Poverty was a given, he said, but “even if you have bad parents, [the schools are] still getting the best kids the parents’ got . . . they’re not hiding the good ones at home,” he said.

He said since the intervention, 100 per cent of students have gone to college and test scores are up.

“I don’t think it’s a matter of economics. I think it’s a matter of political will,” he said. “We know what to do.”

Mr. Summers said the education system as a whole needs to be revamped. “The barriers do not come from the top one per cent; they do not come from capital,” he said. “The primary segment of the American economy that is run not to satisfy the customers but to satisfy the providers is the education system . . . it is run for the convenience of administrative bureaucracies.”

But some said the problem goes deeper. “Once we fix these schools —and I agree that is the starting point — my clients look at me and say, ‘Lady, are you nuts, there are no jobs left,’ ” said Ms. Rice.

“That’s right,” Mr. Simon chimed in.

“And we cut off the transportation system so they can’t even get to the jobs,” Ms. Rice added. “We have no intention of having these folks join anything except our prison system.”

“We are the people who can force a change,” she continued, saying the system is “so stuck on stupid it’s mind-boggling.”

Ms. Hunter-Gault prompted the panelists to offer advice for the new president in 10 words or less.

“Rebuild infrastructure and renew educational accountability,” Mr. Summers said. “Education to the 10th power,” Mr. Fryer said.

“Win back congress, do infrastructure and education like all get out, and end the war on drugs,” Ms. Rice said.

Ms. Boushey echoed the previous three, “plus focus economic policy on ways that will grow the middle class and reduce inequality, because that will also help growth moving forward.”

“Rebuild infrastructure, education, end the war on drugs, and I’ll add one last thing, which is begin talking again about the urban poor,” Mr. Simon said. “When was the last time you heard either of [the presidential candidates] even mention the idea of the urban poor. They don’t exist in our political climate.”

Panelists pointed out that the engaged audience could have been at the beach and instead had gathered to mull these deep-rooted problems. They offered advice for going forward: demanding accountability from elected officials, visiting a public middle school and Mr. Simon’s suggestion of nullifying juries.

“The reason this problem is not solved is that those who are prepared to do it don’t get enough support,” Mr. Summers said. “Find the reforms that you think work and support them . . . the time for speeches and panels is ending; the time for executing on what works is beginning.”

“You have your marching orders,” Ms. Hunter-Gault said.

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »