Belle, originally of Tashmoo, spent the last two winters in South America and just got back in May. Now she is spending most of her time fishing Tisbury Great Pond with four of her friends.

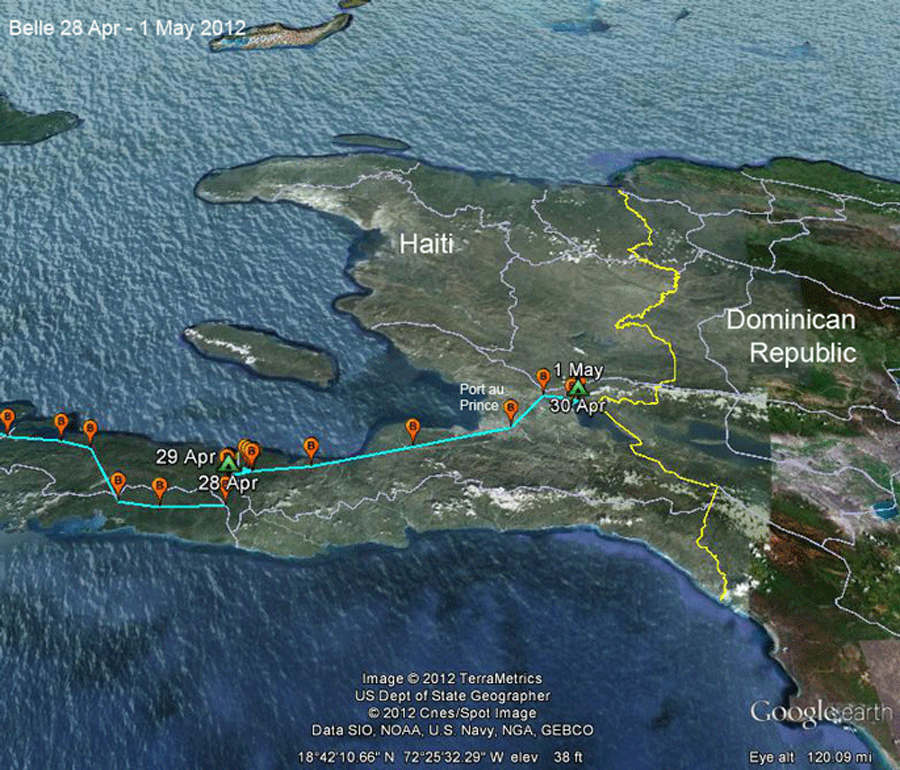

Belle’s journey home was far from routine — something about a mysterious delay around May 1 near Port au Prince. Her friends were worried she’d been killed, but Belle proved herself a survivor. She is very much alive but is keeping mum about her trip.

Richard O. (Rob) Bierregaard Jr., 60, a scientist at the University of North Carolina, is among the happiest about Belle’s safe return. “We were stone cold certain she was dead on April 30,” said Mr. Bierregaard, who has been monitoring all of Belle’s activities.

Two-year-old Belle is one of a pioneering group of osprey being tracked by scientists all over the world. Sporting a tiny backpack equipped with a transmitter, she provides a map of her day-to-day life and travels. Researchers hope that through such data, they will understand how these birds learn to fly great distances and eventually find their way back to the same place year after year. The 30 gram transmitter, powered by a solar cell, communicates via satellite and reports her position. Belle is watched avidly on the Internet by scientists and youths of all ages.

Today, Belle is part of a healthy, thriving Vineyard osprey population that has bounced back from dangers posed by pesticides and humans alike.

With the help of assistant Dick Jennings, Mr. Bierregaard put the transmitter on Belle two summers ago, on the morning of July 28, 2010. At the time she was probably 10 weeks old.

Named for one of her sponsors, Belle is part of a backpack-wearing flying squad that ranges from South Carolina to New Hampshire to Cape Cod and the Vineyard. She joins ospreys with names like Buck, Henrietta, Sanford and Tucker. Since 2004, there have been 35 juveniles (19 on the Vineyard) plus 19 adults (seven on the Vineyard) tagged with transmitters.

Mr. Bierregaard has gotten to know many of the birds through his efforts to follow their travails.

Though the backpacks may constitute “a slight burden on the bird,” Mr. Bierregaard said, the devices have helped establish that birds are capable of having a full life. They are helping the science community understand considerably more about their annual migratory habits over thousands of miles.

Interest in tracking the osprey, particularly the juveniles, stems from the huge unknowns associated with what these birds do before they settle down.

“We knew back in 2000 where the adult ospreys were going. We had the basics. The males and females leave in August and they go their separate ways,” Mr. Bierregaard said. The following Vineyard spring, the couples come back together at the same nest. The female usually has three eggs.

But they knew relatively little about the young ones.

Mr. Bierregaard said ospreys begin their lives with a compass and a clock and proceed to learn from their experiences. The first year of an osprey’s life is the most critical. “There is a high mortality rate in the first year,” he said. “It is natural selection. They have to have good genes and they have to be lucky.”

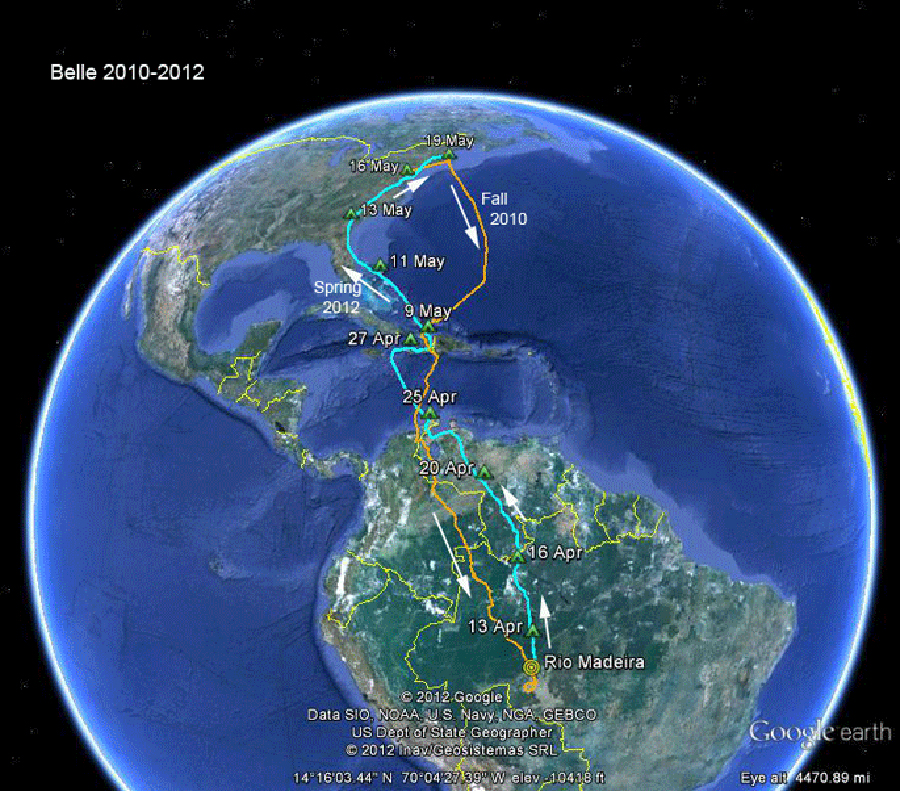

The ospreys that will be hatched this year are still in their eggs. By the end of the summer, they’ll be flying. In the fall they’ll head south without a map. Mr. Bierregaard said the birds know they have to fly south. Many of them will fly over the ocean, many will fly over land. But it is in that first trip south that they learn something about the route to South America. Belle spends the winter in Brazil, mostly.

In the second year, each bird’s trip back to the north is usually closer to the coast than the preceding trip. These birds not only use their inborn compass, they also build on previous experience. There is navigational learning going on in every trip. “They fly south. Then something in their brain tells them to stop migrating,” Mr. Bierregaard said. “They find a place and spend the winter.”

Belle spent January in Porto Velho, capital of the Brazilian state of Rondônia, near the Amazon River. She spent February near Rio Madeira. “She has her favorite places,” Mr. Bierregaard said.

Mr. Bierregaard feels a kinship with this avian traveler. Belle has established a personality. “She is all business,” he said. “When it is time to migrate, she takes off and heads south. She may stop for a few weeks. Again, when it is time for her to come back to the Vineyard, she gets to business and pretty much flies straight home.”

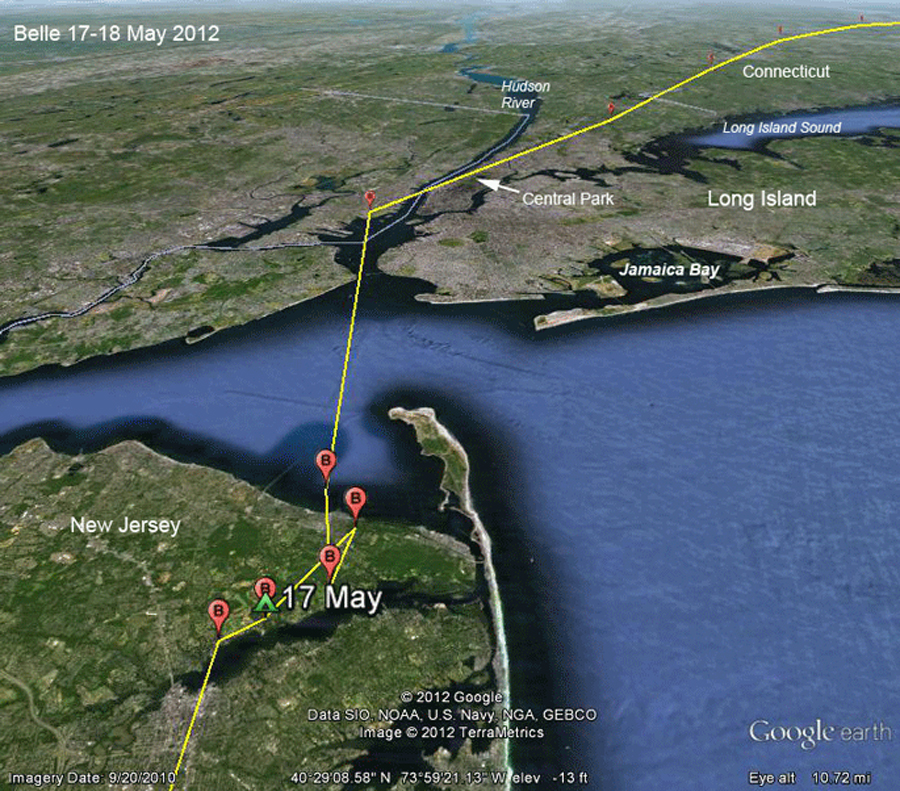

This spring, her flight from Florida to the Vineyard took six days. Mr. Bierregaard said he watched her fly over the Caribbean Sea, and saw her waver from a direct trip. Instead of going straight to Cuba, as she should have, she diverted to Haiti. Starting around April 30, Mr. Bierregaard had three days of tremendous concern about Belle. It looked like either she had dropped the transmitter or been killed. For two days, there was no movement at all.

She could have discovered a fish farm. But it is also widely known that ospreys can get shot near fish farms, where they are considered a pest.

“Something happened,” he said, though he is at a loss to say what, exactly. To fit the mystery, Mr. Bierregaard said, “I am thinking of changing her name to Phoenix.”

Though the osprey on Martha’s Vineyard and other places along the Atlantic seaboard are doing well, there is concern about the dangers they face each winter. In addition to the perils near fish farms, they are also targets in the Domincan Republic, where farmers think ospreys will kill their chickens. “They think they are big hawks,” Mr. Bierregaard said, adding that ospreys don’t eat chickens. Others have been known to hunt osprey for their meat.

Such human behavior has not been limited to Central and South America. They were once shot right here on the Vineyard, where they were thought to be pests.

In addition, the osprey population on the Vineyard and nearby has come back after being severely reduced through the use of the pesticide DDT.

Mr. Bierregaard credits Gus Ben David of the World of Reptiles and Bird park in Edgartown for having worked hard with others to help the bird come back. Years ago, he said, “there used to be [only] four or five nesting pairs [on the Vineyard]. Now there are 80 pairs and 115 nest poles.”

“With DDT out of our system, ospreys have proven to be robust. They are now thriving. They are amenable to our living. If Martha’s Vineyard were to secede from the nation, the osprey would be the Vineyard’s national bird.”

Belle is expected to have a great summer on the Vineyard. Mr. Bierregaard because most ospreys don’t start breeding until their fourth year, at this point Belle is likely looking for a nesting site.

Mal Jones of West Tisbury lives near the Tisbury Great Pond shoreline and has been watching five juvenile ospreys, one of which is Belle. Mr. Jones said the birds have been here consistently feeding, diving into the water and rising out of the swirling water with a small fish in their talons. “I usually first know they are here when I hear a big splash,” Mr. Jones said.

To watch Belle and other birds like her, visit the following ospreytrax.com.

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »