It was a clear night on top of Mount Washington in New Hampshire last Saturday; the temperature was 31 degrees a few hours after the sun had set. But Vineyarders didn’t have to travel to experience the weather at the highest elevation in the Northeast. A virtual trip sufficed from inside the comfortable conditions at the Martha’s Vineyard Hebrew Center.

Jeff DeRosa, outreach coordinator for the Mount Washington Observatory, had traveled off the mountaintop and down to sea level for a presentation about the place known as home of the world’s worst weather. The event was hosted by the Felix Neck Wildlife Sanctuary in an ongoing effort to increase the sanctuary’s weather-based programs.

Mr. DeRosa said the Vineyard and Mount Washington share two things in common — high moisture levels and a location as repository for nearly all major weather systems in the country.

“Martha’s Vineyard deals with same thing Mount Washington does because we are affectionately known as the tailpipe of America; most of North America’s weather comes right over us in New England,” Mr. DeRosa said. “It all ends up here.”

Mount Washington collects more precipitation due to orographic lifting, a phenomenon when an air mass is forced from a low elevation to high elevation as it moves along the terrain. As a result, the temperature drops three to five degrees every 1,000 feet in elevation.

And of course there is more snow up there. On average, the Vineyard receives about two feet of snow annually. Mount Washington receives 26 feet.

The observatory is best known for measuring wind speed. For 60 years it held the world record for the highest wind speed on record, at 231 miles per hour. The record was shattered last year on an island off the coast of Australia during Cyclone Olivia, where wind gusts measured 253 miles per hour.

“We’ll get it back,” Mr. DeRosa said.

The mountaintop is home to a group of observers who monitor conditions around the clock in 12 hour shifts, spending a week at a time on the mountain. There are three ways to get to the top: by train, car or hiking.

In winter the observatory does not even try to plow the road, instead using snowcats to drive through 25-foot drifts.

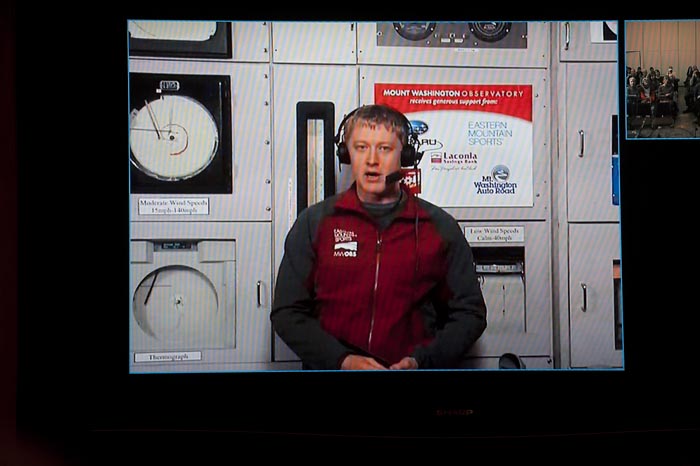

Observer Brian Clark spoke to the audience live from the weather room in New Hampshire.

“Modern forecasting is done mostly with computer programs, thousands of data points and then use math and physics to figure out what weather is going to do in the future,” he said. “That’s where we’re valuable — we’re like a weather balloon sitting at 6,288 feet, 24 hours a day 365 days a year.”

Mr. Clark gave a tour of the small room and explained the difference between pressure at sea level and mountain elevation.

“It’s about a 20 per cent difference in the numbers between sea level and mountaintop,” he said. “That means I’m breathing 20 per cent less oxygen than you are because the air is 20 per cent thinner. To give you a comparison, Mount Everest has 70 per cent less oxygen than you expect to find at sea level.”

The observatory’s anemometer is unique and relies on a technology typically found on an airplane that calculates the speed of the plane as it flies through the air. The anemometer works inversely, measuring the speed of the air that flies through it.

The device is required due to the presence of rime ice, which is actually frozen fog. Rime ice forms on literally everything at the top of the mountain, and observers must go out hourly to scrape the ice from monitors.

Working in 100-mile-hour winds is no easy feat, Mr. DeRosa said. He said those who can walk around the entire observation deck of the observatory make it into the Sensory Club.

“Anyone who says they’ve done it, I think they’re lying,” he said with a laugh.

Comments

Comment policy »