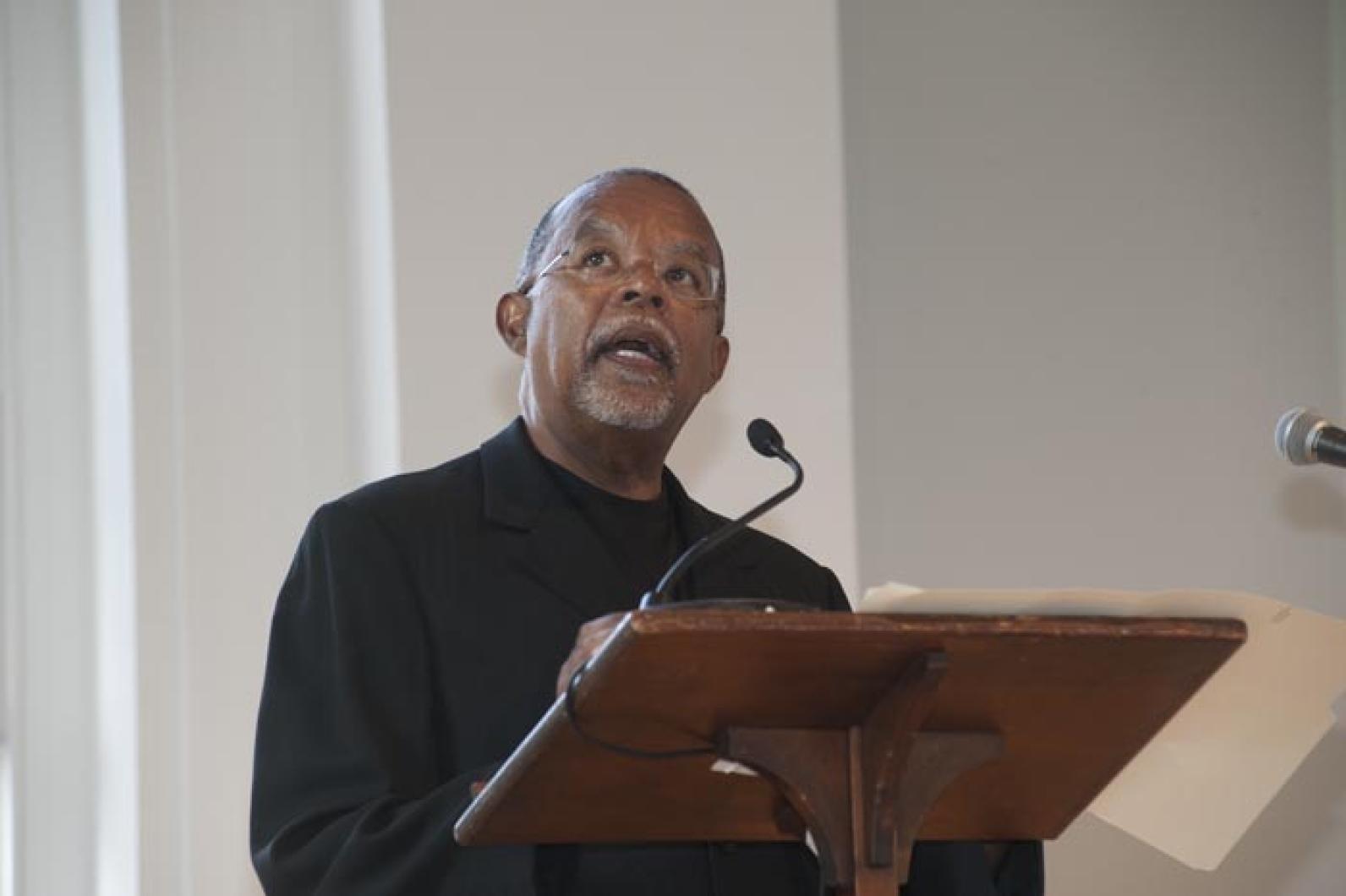

Since 1968, the black middle class in America has quadrupled, Henry Louis (Skip) Gates told a packed house at the Edgartown Whaling Church on Thursday evening.

But that was the only positive news in an otherwise bleak survey of the state of black education by a panel of experts convened by Professor Gates and the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research.

Professor Gates referred to that growth in the middle class only to make a point of contrast: That over the same period of time, the number of black children living at or below the poverty line had remained the same, about 35 per cent.

The topic for the night was Separate but Unequal: Closing the Education Gap, but the talk addressed a whole lot more “gaps” than just education, including the developmental gap, the cultural gap, the punishment gap, the political gap, and, above all, the economic gap.

While the focus was on African American attainment, the implications of what was said reached far wider, touching on the achievement gaps affecting other minority groups and impoverished whites and to the future of the nation as a whole.

Unless things improved dramatically, one panelist pointed out late in proceedings, America was looking at a near future where half the population had at best eighth-grade levels of competency.

Professor Gates started things off with a depressing statistic. A recent College Board report had found “one in two men of color, aged 15 to 24 who graduate from high school, is going to end up unemployed, incarcerated, or dead.”

“And that’s among those who graduate,” he said. “What about those who drop out? What are their chances at subsistence, a meaningful, decent life. What happened to our people?”

He recalled that when he was growing up in the 1950s and 1960s, “the blackest thing you could be was an educated man or woman, not an entertainer or an athlete.”

Black people, he said, had valued education “stealing a little knowledge,” he called it since the days of slavery. Teachers once had an “almost godlike” status in the black community, and public schools were “sanctuaries and communal sites of hope and aspiration.”

But now, with the school system falling apart, the educational progress which had lifted people like him had stalled. He called for “the equivalent of a new civil rights movement” to confront the failings of the educational system.

“Dr. King did not die so a small percentage of us could make it while the larger percentage remained mired in a cycle of poverty,” he said, before turning the discussion over to the panel to first analyze the problem, and then offer some solutions.

The first panelist called upon by the moderator, Chalayne Hunter-Gault, was Angel Harris, an Associate Professor of Sociology and African America Studies at Princeton, who quantified the educational gap.

On average, he said, black and latino students were graduating high school “with the same skill set that whites had in the eighth grade.”

And while from the 1960s to 2000 there was a slight narrowing of the attainment gap, it was so slight that it would take 60 years in reading and 100 in math to achieve equality.

The unrealistic goal of closing those gaps by 2014, set by the No Child Left Behind policy, of President George W. Bush, he said, indicated a “lack of respect for the problem.”

The No Child Left Behind policy, with its emphasis on standardized tests and a regimen of punitive measures for schools which did not measure up, was almost universally condemned by the panelists.

The second panelist, Diane Ravich, Research Professor of Education at New York University and a senior figure in education under both the first President Bush and President Clinton, at one stage called it “the most ridiculous piece of legislation ever passed by Congress.” It used testing as punishment, she said, threatening to humiliate and fire educators who did not meet its “impossible” standards of annual improvement in “invalid” testing.

The initiative had failed even by its own standards; this year 82 percent of schools would fail.

The major reason for poor educational outcomes, in America or anywhere else in the world, was poverty, she said. She offered evidence too.

For all the publicity about American students comparing poorly to those in other developed countries, this was not uniformly true. “In fact, in low-poverty schools in the U.S. the test scores were higher than in [world leaders] Finland, Japan and Korea,” she said. Where the schools had 25 per cent poverty, the test scores were equivalent to those countries. The real reason for America’s lower overall results was that “we lead the world in child poverty.”

That poverty had become more concentrated as black, middle class families left inner cities and as the manufacturing base of cities had declined. On top of that was the “dramatic crisis of incarceration. The black incarceration rate is eight times the white incarceration rate,” she said.

Professor Ravich quoted Harvard sociologist Bruce Weston, saying that American society made a decision in the 1960s. It could have addressed the yawning social gap between the races, but instead chose to build prisons.

James Comer, Professor of Child Psychiatry at the Yale School of Medicine, countered by saying it was more complex than blaming poverty alone. He was a child of poverty, with a mother who had less than 2 years of school, and a father who was a laborer with a sixth grade education.

The difference between him and so any other poor kids, was “the quality of the developmental experience that I received at home that they did not receive,” he said.

He also stated that despite the “exclusion and abuse” of African Americans in the past, there was at least a measure of employment security. But starting in the 1950s, the number of low-skill jobs for the poorly-educated had declined. As a result the number of dysfunctional families had risen. The number of children born into dysfunctional families had risen even faster. The evidence showed that functional families had fewer children, while the most dysfunctional often had five or more.

“In three generations, what you had was an explosion of the dysfunctional families” he said. This meant more children reaching school age who were underdeveloped in the skills they needed to cope.

The fourth panelist, Michelle Rhee, drew on her experience as chancellor of the Washington, D.C. public school system between 2007 and 2010, to talk about the practicalities of dealing with a failing system.

When she took her job in Washington, she said, it was generally known to have the worst-performing schools in the nation. She gave some examples of what she encountered: Having heard “countless stories” of children without text books, she found the system did have them, but they had not been delivered; hundreds of teachers went months at a time without being paid; one teacher had paid for 18 months for health care, then when his wife went to the emergency room he found out the system had not signed him up for it; she decided to buy 6000 computers for all the school classrooms only to learn most school wiring systems could not cope with them.

Among the changes she did make were instituting breakfast programs in addition to lunch programs — and later even supper programs for children who were not being fed at home. She also put nurses in every one of 123 schools, and established access to art, music, PE, librarians and social workers or guidance counselors.

She condemned the influence of politics, recalling a meeting with a group of politicians to discuss closing 23 schools and having one confide that he thought the measure was necessary and inviting her to “close as many as you want to as long as none is in my ward.”

Ms. Rhee differed somewhat from the other panelists in laying substantial blame at the feet of teachers and school administrators.

In D.C.in 2007, only eight per cent of eighth graders were performing at grade level in mathematics, she said, and yet the performance evaluations of the adults in the school system found 95 per cent were rated as doing an excellent jobs.

“You can’t have a functional system with that kind of disconnect,” she said.

While she acknowledged the societal and cultural issues referred to by the other panelists, Ms. Rhee said a significant part of the problem related to the “utter lack of accountability” in the system.

As to solutions, the panel proposed a variety of measures, starting even before birth and extending well beyond school. Improving prenatal maternal health would help because one-third of low birth weight babies have learning difficulties. Reforming the justice system so it did not lead to the world’s highest imprisonment rates would make black families a whole lot more functional.

Among other generally-agreed measures were: placing greater emphasis on early childhood education; better training of teachers in how to deal with children coming into the system with underdeveloped skills; smaller classes, which had been shown to be of particular benefit for African American children; more emphasis on basic nutrition and health, and; less emphasis on standardized tests, or at least a less punitive response to them. There should also be more research into why successful schools work.

There were also points of disagreement. Ms. Rhee firmly held that too many bad teachers were allowed to continue in the system. Others, notably Ms. Ravich, strongly disagreed.

But ultimately the real problem was not with the teachers, the parents, or the kids. The fifth panelist, who summed up the other four, Lawrence D. Bobo, the W.E.B. Du Bois professor of Social Sciences at Harvard, hammered this home.

It was poverty. The country that had a record of slavery, Jim Crow laws, ghettos and now mass incarceration also subjected its black population to a kind of poverty almost no whites experienced, he said. It was a poverty where many children existed at 50 per cent below the poverty line, in neighborhoods where virtually everyone else also was in poverty, and where almost no men had jobs.

And you can’t fix the schools without fixing that.

Comments (3)

Comments

Comment policy »