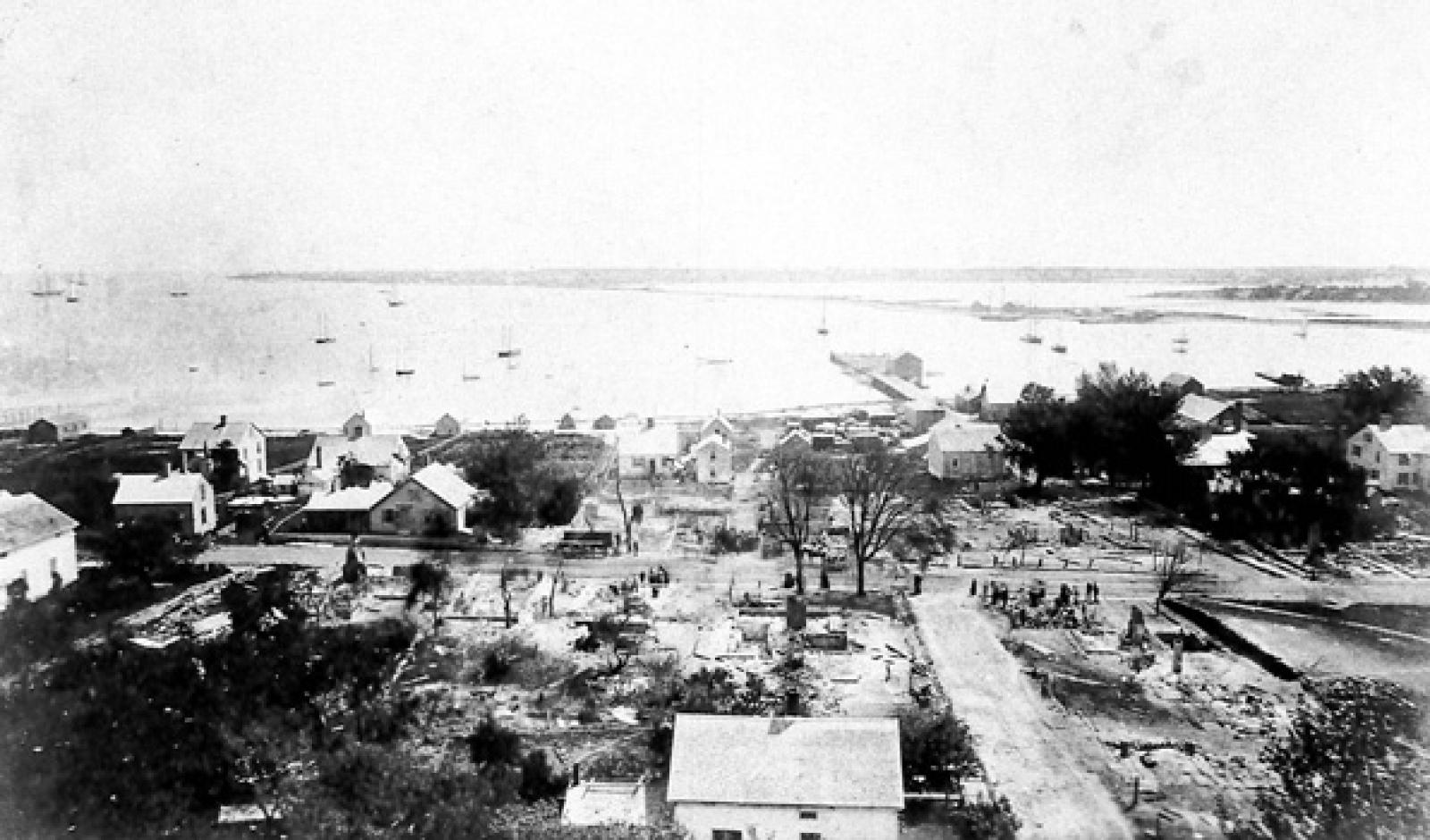

The Tisbury fire, which began one summer evening in the very heart of downtown Vineyard Haven, destroyed 62 buildings valued at $200,000. Photographs of the center of the village the next morning show smears and patches of black spread across a grid of lanes and roads. Every store but one burned to the ground.

Samuel Keniston was an energetic editor, but one weeps over his judgment here. Whatever he wrote about the fire, which happened on a weekend, he put into the Monday edition of the Cottage City Chronicle, a supplement printed for vacationers in Oak Bluffs Ñ and that copy of the Chronicle is lost.

In the paper of record at the end of the week - the Gazette - he merely picked up the story where the Chronicle left off, writing about the buying and selling of ruined lots and of early efforts to rebuild, then offering little more than a few editorial notes about how well the town had tried to fight the conflagration.

Almost 40 years later, fortunately, a pair of youthful new editors - Elizabeth Bowie and Henry Beetle Hough - decided to record the story again, interviewing Vineyard Haven residents who still remembered it. For the sake of history, we excerpt this excellent account of the Tisbury fire.

From the Vineyard Gazette edition of August 5, 1920:

On a black night almost 37 years ago, August 11, 1883, a summer visitor stood on Vineyard Haven wharf. As the northeast wind whistled past he shuddered and said, “what a night for a fire.” A chance remark which anyone might make as he thought of a town built of wood, with no means of fighting a blaze except the humble cistern and the bucket brigade. But uttered that night it was remembered through the years. For the fire came.

A hundred years the quaint old village with its friendly harbor which sheltered, during the supremacy of the sailing vessel, 10,000 vessels and 60,000 sailors each year, had escaped the catastrophe which the pessimist was fond of predicting was only a question of time.

But as a matter of fact he expected Oak Bluffs, then Cottage City, to furnish the fuel for a monumental blaze. Vineyard Haven was so quiet, so careful, so old that it seemed no fit setting for the spectacular. Yet, 62 buildings, valued at $200,000 and including every store in town but one, fell before the onslaught of the fire that August night.

A large part of the population was in Cottage City that night, listening to a concert. Many more had finished their day’s shopping or gossiping and left Main street deserted and silent. If you had asked any one of them what he or she would do in case of fire, he would have first laughed off its possibility, perhaps glancing uneasily out into the night meanwhile, and admitted that he hadn’t the slightest idea how to fight a fire and that if a big blaze started the town was doomed.

What the Women Did

But when it came with the sturdy reinforcements of wind and weather and darkness, the town was ready. It was man’s work, every stroke of it that was done the whole night long, but women made it their work, too. Into the breaches of the bucket brigade they flung themselves. Furniture that would have taxed a man’s good right arm, they moved as if it had been pasteboard. Generalship which seemed to desert many of their husbands and fathers, they gave.

“The women! How they did work. Why, lots of the men - understand a great many more worked like Trojans - stood around in the streets and didn’t seem to know what to do. They’d stand right by houses that were burning or in danger and not seem to think of using water on them. Women had to crowd past them to get to the cisterns. If you’re writing up the fire, don’t forget to tell the women’s part in fighting it.”

This from Rodolphus W. Crocker, who naturally remembers the fire as well as anyone, considering the fact that the harness factory where he employed some 80 men was the first building to go, and that he spent the night half suffocated on this roof and that roof, soaking them with water and putting out ambitious little blazes.

It was hard to get the women to admit that they had done anything worth talking about. Most of them were more willing to discuss the fire in general or another’s part in it, than their own. Mrs. Charles E. Lord, whose mother’s house was in the line of fire on Main street, remembers the effective manner in which her mother took charge of the situation and really deserved the credit for saving the house. And she also introduced the story of the “hero in the derby hat.”

The flames had swept up Main street with such speed and had done their work so thoroughly in passing that as they stuck out their hungry tongues to envelop the Daggett house, the men in the vicinity assumed a fatalistic attitude and opined that it was useless to combat the elements.

Mrs. Daggett thought differently. She announced to the assembled multitude that the house could be saved if she could find anyone to help her.

Enter the Hero in the Derby Hat

Then the hero in the derby hat approached.

“Madam,” he said, “I am at your service.”

Mrs. Daggett led the way to the attic, where the good Samaritan removed his precious derby, to permit her to bind his head in flannel soaked in water. Then he took up his post at the top of the ladder leading to the roof, where if the flames did not touch him, their heat scorched his face. Because of his example and hers, the men in the street set to with a will, baled out the cistern and passed up the water bucket by bucket until the danger was past.

Before she could reach him to thank him for his aid, “the hero in the derby hat” had slipped away and lost himself in the crowd. Only the derby remained. Some days later Capt. William Buckley, whose large and varied collection of head gear had been lost in the excitement, was presented with the derby of the nameless hero whose identity has never been discovered from that day to this.

Mrs. Rebecca Getchell spent most of the night caring for the homeless, in particular a woman who suffered agonies from sciatica.

Mrs. Elnora D. Luce occupied a house which was at the extreme northern end of the line of fire. Its escape was miraculous, for it was near the hottest of the fire which raged in the harness shop, located where the Martha’s Vineyard National Bank now stands and the paint shop next door. This house, the sole survivor for some two blocks down Main street, still stands, its trim white charms indicative of the beauty of the winding old street which was largely lost in the rush to rebuild.

Mrs. Luce is more than 90 years old now, and she says that her memory is not what it used to be, but even so, it is much better than the average.

Didn’t Feel Frightened

“I didn’t feel frightened at all. I felt just as calm as could be,” she said. “Did the women work? Yes, lots of them. My house was full of women, all of them busy. It’s queer what people will do when they get excited. I found a man tearing off a door between two rooms. He said he was going to save that from the fire. It took me some time to convince him that if the house was going to burn there wouldn’t be much use in saving the door. Some people insisted on trying to save their blinds.”

“It all seems like a dream to me. I have never been able to think of that terrible night as something real,” said Mrs. Stephen C. Luce, whose husband, now postmaster, kept a general store at the time. “I remember that I was up in the library, run by the Ladies Library League, when I heard the fire bells. I went over to the store and found Mr. Luce telephoning to Cottage City for help. They sent the chemical engine over. Then he filled a market basket with his books and records, and came home.”

They were living then in the comfortable house they occupy now, on Spring street, a few hundred feet from Main street. Although heroic work saved it, the house next door, belonging to Mr. Gilbert Brush, and one across the street, where the Baptist church now stands, were fired by cinders and burned to the ground.

“Burned to the ground” is not so suggestive of the facts in a big city fire where the steel, concrete and brick skeletons of the victims still remain, if blackened and twisted. You would not know that wood could be reduced to such little piles of ashes, that great timbers could be utterly consumed, that burned house furnishings could leave no trace of their passing unless you had seen Vineyard Haven on its morning after. So utterly had the familiar landmarks of Main street disappeared that some old timers found it difficult to get their bearings when they ventured forth. A tribe of homeless cats was abroad too, suffering as only such home lovers can suffer.

Thought House Burned

While men were busy soaking the roof with water and putting out the small blazes that started in spite of it, Mrs. Luce had her hands more than full helping to remove her household goods to a place of safety. This done she went to her mother’s house and helped move things there, and watched the destruction of the elder Mrs. Luce’s dwelling. Then she made her way to the beach where with hundreds of others driven out by the flames, she spent the rest of the night. Flames rising from what proved to be a wood pile at the Brush house convinced her early in the night that she too was in the homeless plight of so many others, so that with dawn and her return, her sense of relief at finding her house uninjured can be imagined.

On her pilgrimage from her house to safety, Mrs. Luce carried two charges, one her bird in a cage, the other a carving knife which she had picked up and was caring for with the utmost solicitation. Before she reached journey’s end, however, she had dropped it on the ground and heard its fall after her careful cherishing without the slightest concern.

Thirty-seven years after the fire, there are still anecdotes to be had for the asking. It seems as if the events of that night had burned themselves into the minds of the people who lived through it as permanently as its flames had laid waste their houses.

Mrs. Lord remembers that Charles Smith, whose house stood where the Lane block is, forced to vacate his house in a hurry, carried out one thing with great care. It was a box of Gay Head clay. Capt. W.A. Luce, whose store was burned, saved a basket of summer savory.

George Dean, who was a youngster at the time, remembers an incident in connection with Wendell Crocker, who kept a Main street store. Boy-like he rushed into the store and inquired of Mr. Crocker what he would like to save from the flames.

“Save the things of most value,” said the old gentleman in a quavering voice. Then, not suiting action to word, he seized a box containing one strip of the penny candy which has now vanished from the face of the earth, and bolted down the street with it.

Served Ice Cream During Fire

“I remember something else about the fire that I think was funny,” said Mr. Dean. “Ben Dexter was standing by the door of his ice cream saloon with an axe, keeping people out. We boys, three or four of us, ran around to the back and climbed in. We took the freezers of ice cream and those cocoanut cakes he used to make, to a vacant shed, and we served ice cream to every one who came along. Anyhow, we saved the cans and that’s more than Ben would have done.”

Incidentally, Ben’s proficiency in the art of whittling contributed the biggest thrill of the evening. For great was the lamentation when it was discovered that the figures of human beings were being consumed by the flames. They turned out to be nothing more nor less than some wooden Indians that Ben, conceded the “greatest jack knife expert I ever saw,” had made in his idle hours. The destruction of Ben’s ice cream saloon, which was ablaze 15 times before the fighters had to give up hope, was nothing more nor less than a calamity to the young people of the town who had laughed at the old man’s strange ways but conceded that his ice cream (frozen custard) and his flat cocoanut cakes, which many a Vineyard housewife makes on state occasions, were the best ever known.

You have heard the old saying about throwing the mirror out of the window and bringing the feather bed downstairs and putting it carefully on the ground. But, perhaps you never believed that it could happen. Perhaps it never did, except in the Vineyard Haven fire, and George Swain is the authority for its occurrence then. His experience was not the least hectic of all, for he owned several houses and was kept busy looking out for them and directing the work of rescue. When the roof of his barn caught fire he threw a bucket of water on it. The next day he measured the distance, for the bucket still lay on the roof. And he discovered that he had tossed it eight feet up, a feat that a circus strong man might have envied.

Comic Relief

The town records saved but deposited bottom side up in a brook, so that they were badly damaged; best bonnets discovered afterwards in hen houses and in trees; buckets, caught up in a frenzy of excitement and tossed into wells without a rope Ñ Captain William Cleveland found eight of them in his well next morning; desperate attempts to rescue pianos by sawing off the legs or even hacking them off; an attempt to wrest a bucket from an unwilling owner only to discover that his reluctance was due to the fact that he had $3,000 concealed in it . . . such incidents furnished the comic relief in what promised at first to be a story fashioned of tragedy all wool and a yard wide.

It is almost impossible to imagine the thousand and one tasks that were forced in one night upon an unprepared population. Carpets must be torn from floors, soaked, and spread over walls and roofs. There was the salvaging of quantities of household goods. It was not enough to dump them in the streets. There must be wagons, the horses maddened by the roar and crackle of the flames, to convey the goods into fields and woods far from danger. There must be strong arms and gentle to move the sick and nervous to a place of safety. One old lady, Mrs. James Davis, had a fit that dreadful night, and died the next day. Mrs. Cynthia Chase, 94 years old, was burned out of her house. There must be water, drawn so generously from wells and cisterns that their owners were in danger of going unwashed next day. And there was aid and comfort for the needy. This came from all over New England and even farther, where news of catastrophe to an Island home, to a summer residence or to a brave community of fisher and farmer folk facing their loss with resignation brought immediate and generous assistance. One of the notable gifts was that of Stephen W. Carey, who wired at once $1,000.

At the Cottage City concert, when the solemn church bells clamored forth the alarm, a man stepped on the stage and recommended calm.

“You are in no danger,” he said. “The fire is over in Vineyard Haven.”

Fire King Yields

Before he had finished, a large part of his audience had vanished and was racing home along the Beach Road as fast as Dobbin could be persuaded to travel. The glow from the fire could be seen for miles, and was plainly visible from New Bedford. The night was thick and there was a little drizzle which, however, did not aid in putting out the flames. And the wind roared up the street in that terrifying way that only the fire king can dictate. He made his last desperate stand at the Mansion house, leaping across the street to burn two or three houses on the other side, then veering off to the west, where he was finally conquered.

Visitors wonder sometimes why the Main street of Vineyard Haven does not boast in such profusion the quaint, comfortable old houses, and the magnificent trees which mark the rest of the town. Visitors wonder. But Vineyard Haven folk know. For they remember, can never forget, their supreme test which came rushing to them out of the darkness of an August night, 37 years ago. And the regret for what they lost must be softened by the memory of their heroic meeting of that test.

Comments