It is inherent in the human soul to be thrilled by the sight of wind-hardend canvas, even if it is only a picture. There are tales and traditions of men who have been highly successful master mariners, yet who were born and spent boyhood and youth far, far from salt water or even lakes where boats might have been seen, but who had studied a picture from early childhood of a ship in a seaway and carrying sail.

The Vineyard entertains its share of visitors from in-shore each summer season and again and again they may be seen watching the movements of the little racing craft, or crowding the waterfronts when the Edgartown Yacht Club Regatta is sailed.

That they are fascinated is clear, but many’s the time that such a visitor has been heard to voice regret that he knows nothing of sailing nor even how to identify a craft by her rig. In this sort of visitor’s study of boats the most simple rigging of the smallest craft presents problems which appear most intricate and difficult.

To bear a hand in helping these people to better recognize what they may see as they visit docks and waterfronts, a few sketches of sail plans are here presented and some slight description appended.

Crossed Yards Are Rare

The majority of the sail plans shown are those commonly seen during the yachting season, but they are sail plans only, in most cases. The cutter or sloop rig may appear in many sizes and tonnages, but regardless of size, such craft are cutters or sloops. Crossed yards are rare in Island waters, but they do appear occasionally, and when the Eastern Yacht Club makes one of its visits there are many schooners with rigs that belong to an older day when there was real romance and pleasure in the fitting out of a vessel. There are more gaff-headed sails in this club than in many another, and there is provision for carrying light canvas of a type that is seldom seen locally. But now to deal with more common boats.

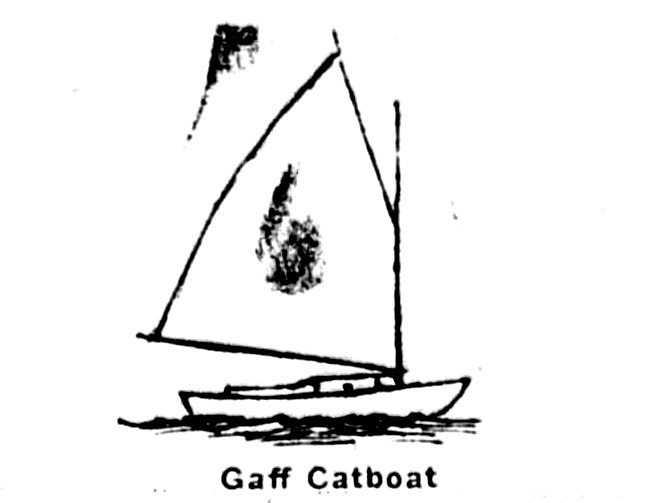

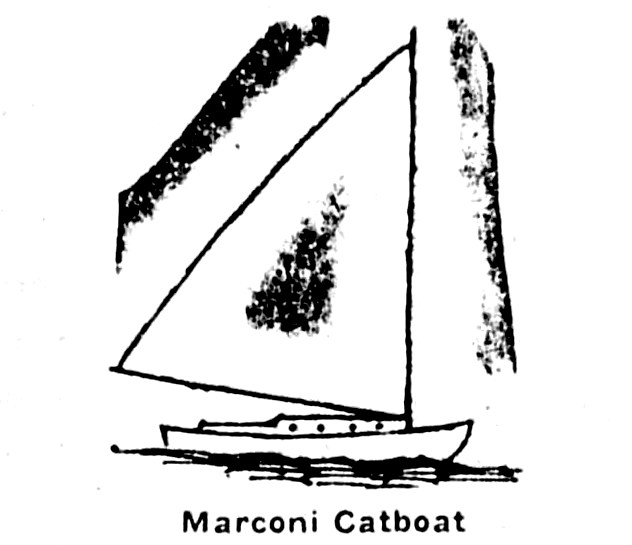

The catboat, which is one of the most convenient of family boats, is returning to its former popularity, both in wood and fiberglass, and even if this coming summer, the Catboat Association fails to rendezvous in an Island harbor, there will surely be members cruising in the area who will anchor for a day or two. The cat rig is most simple, there being but the single sail in the original plan. This sail was originally gaff-headed, that is, it had a spar at the head and foot, and those who love the cat and its tradition still cling to this pattern of sail. Some, however, will sail a cat with a three-cornered sail, a Marconi, if you please, which has no gaff. Old men with weak hearts favor this kind of sail as being easier to handle, but whether or not the catboat seen has gaff or Marconi, it is still a catboat, and this is Lesson Number One.

Cutters, sloops, yawls, and ketches come in assorted sizes and always did. Some are actually tiny, while others sail in the Bermuda races and there have been boats of any of these types which have made long ocean passages.

Sloop Has No Bowsprit

The person who studies the sketches of sail plans, will observe that the sloop of today, has no bowsprit. Its single working job is all inboard. Its mainsail and those of the rest of this list is probably three-cornered, a Marconi. This was not so in years gone by. All such boats of whatever size, except for the Chesapeake bugeye and skipjack, carried gaff-headed sails, and it was not unusual for the medium and larger craft to swing a topmast and carry a sail on it before motors were common.

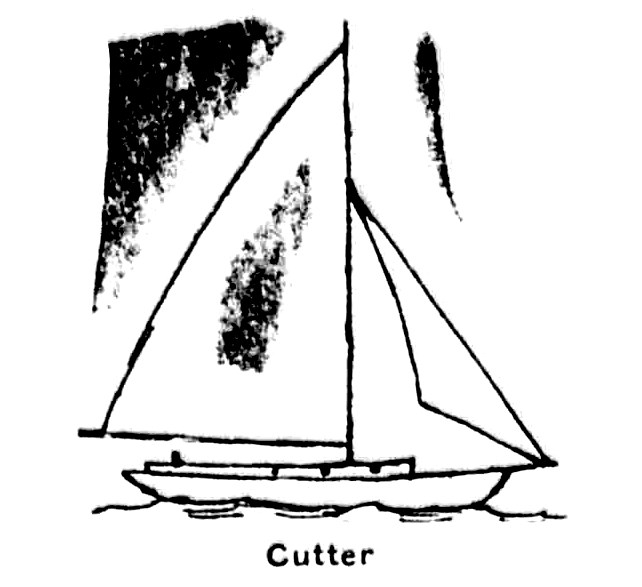

So the sloop has no bowsprit, but the cutter which carries the same sail plan, has a short bowsprit and the mast is stepped farther aft. Actually, the cutter, as a type, is probably older than the sloop, for they were armed naval craft in European waters more than 200 years ago.

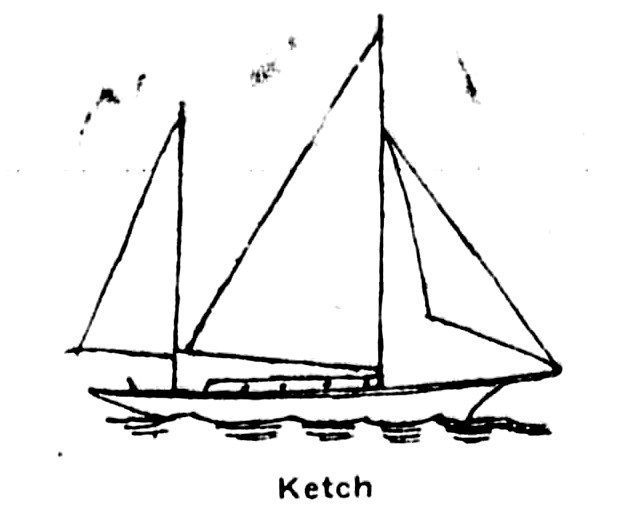

The ketch, which is also a very old craft, has two masts, the one nearest the stern being somewhat shorter than the other. It is theoretically, well forward of the steering gear, and thus differs from the yawl whose jigger is so far aft of the wheel that it is sheeted to a bumpkin extending away from the stern.

The sketches show this difference very distinctly, but it should be added that there are persons who claim authorization for the same, who declare that in a true ketch rig there is a spring stay between the mastheads. Some ketch rigs have this, which is possible if the mainsail is jib-headed. Should it be rigged with a gaff, it might interfere, but the visitor need not worry about these technicalities.

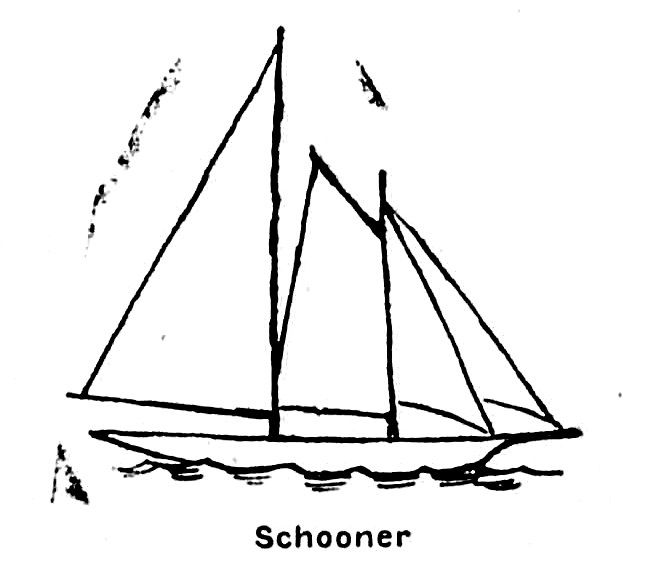

The majority of the schooners one is apt to see today have but two masts and neither is likely to be equipped with a topmast. The coastal commercial fleet has long since disappeared with schooners carrying up to six masts and there was even one with seven. Three-masters, however, were most common and lingered the longest, although four-masters probably made the most blue-water history with their voyages to the West Indies for salt; to Galveston for cotton and with their shuttling between the Kennebec and Potomac all summer with ice.

However, there are a few old schooners, and some not so ancient, sailing today with charter parties out of the Down East ports. There is at least one bald-headed three-master, which means that she carries no topmasts, but regardless of how many masts there may be, if they are fore-and-aft-rigged (with no yards), then the vessel is a schooner.

Along with the single-masted craft, will occasionally be seen the Dutch bouyer, so called big, shoal-drafted and with huge lee-boards on her sides - because she is built to sail the shallow Baltic where a centerboard or keel would cause trouble.

All Ship and No Error

There is nothing else that resembles the bouyer, so you can’t go wrong if you take even a hasty look and decide on her identity. If her sail is set, then the peculiarly bent gaff is one other identifying characteristic, for it is shaped between a plowhandle and the thill of a buggy. But the bouyer is all ship and no error and whatever the reason for this gaff, if the Dutch designers didn’t think it was a good idea they wouldn’t have used them.

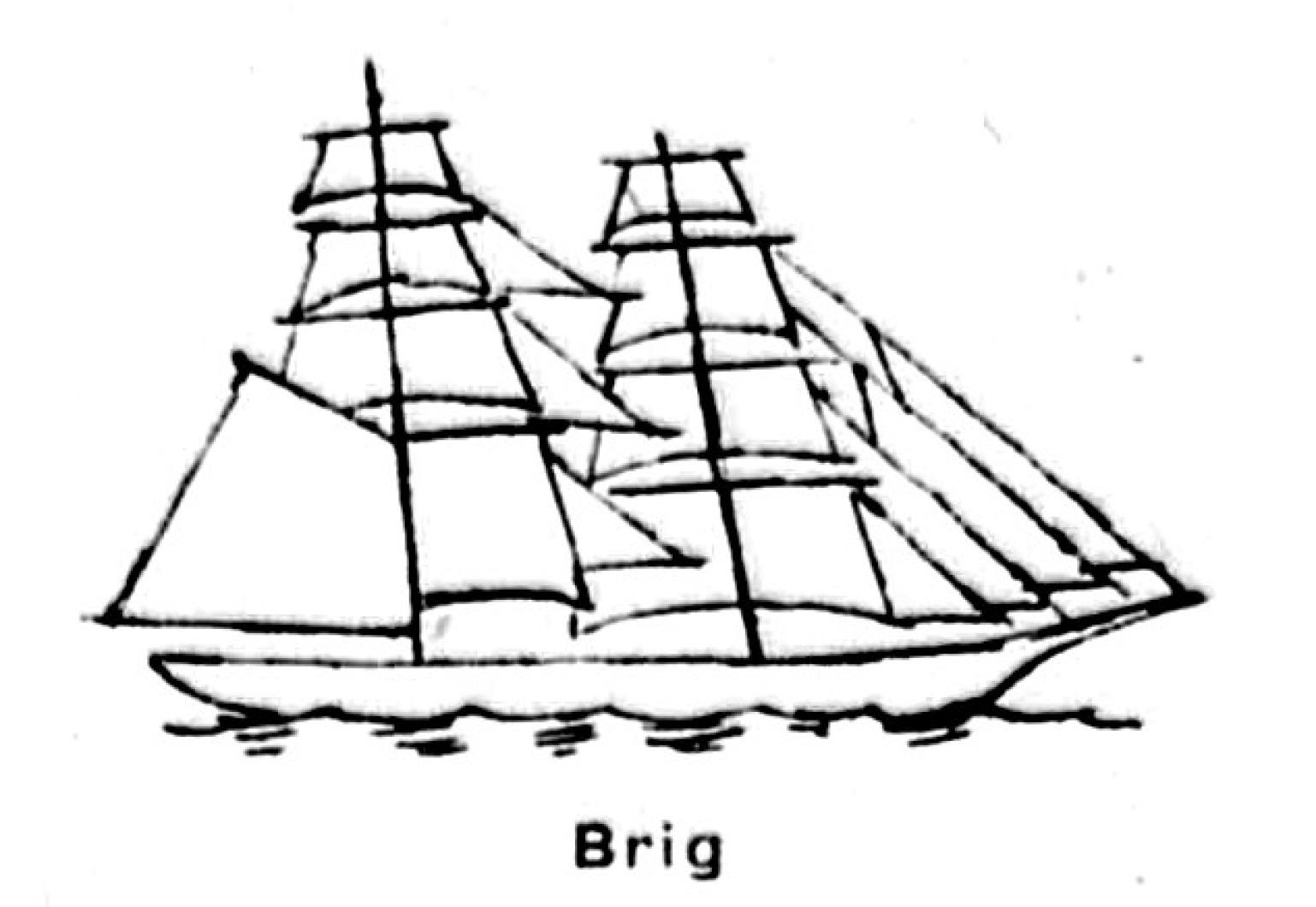

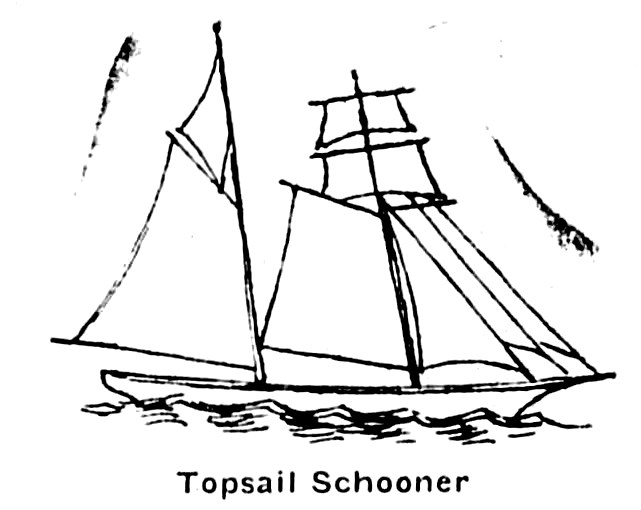

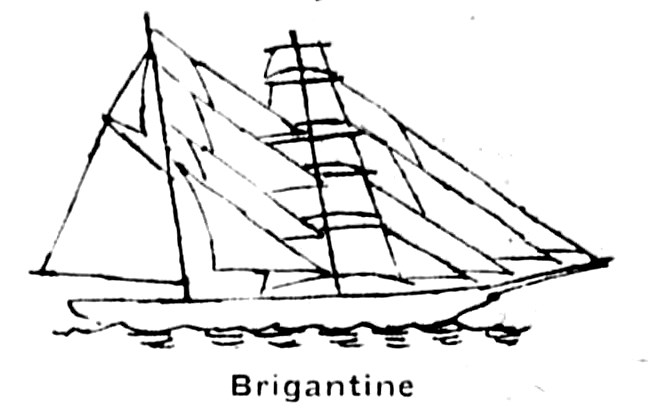

Last of all, there may occasionally appear a brig or some variety thereof. With two masts, both square-rigged, is the brig. With foremost square-rigged and main fore-and-aft rigged is the brigantine. With other combinations of square and fore and aft sails, are the hermaphrodite brig, the jack ass brig, and the snow. It is a peculiar thing, but whenever reference is made to these matters, including the topsail schooner, there is always some ancient barnacle who rises from hibernation to swear by the Great Hook-block that the writer is wrong! The worst part of this is that as likely as not the old barnacle is correct!

There is no point in mentioning other square-rigged craft. It has been many a year since a full-rigged ship anchored in a Vineyard harbor and as for barques and barkentines, they are seldom seen today on this side of the Atlantic and are none too common elsewhere.

But it is hoped that these notes and sketches may help the visitor from inland to identify those argosies which may lift and move between him and the horizon, and if, by chance he may raise a shape that appears to be two or even three boats lying alongside each other, these will be a catamaran, copied to some extent and principle, from the South Pacific natives’ boat, or the trimaran, by which someone attempted to go the Pacific natives one better, and failed.

Drawings by Consuelo Joerns.

Comments